- Home

- Mary Downing Hahn

A Haunting Collection

A Haunting Collection Read online

Contents

* * *

Title Page

Contents

Copyright

Deep and Dark and Dangerous

Dedication

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

Wait Till Helen Comes

Dedication

Map

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

All the Lovely Bad Ones

Epigraph

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

Read More from Mary Downing Hahn

About the Author

Deep and Dark and Dangerous © copyright 2007 by Mary Downing Hahn

All the Lovely Bad Ones © copyright 2008 by Mary Downing Hahn

Wait Till Helen Comes © copyright 1986 by Mary Downing Hahn

All rights reserved. Originally published in hardcover in the United States by Clarion Books, an imprint of Houghton Mifflin Harcourt Publishing Company, 1986, 2007, and 2008.

For information about permission to reproduce selections from this book, write to [email protected] or to Permissions, Houghton Mifflin Harcourt Publishing Company, 3 Park Avenue, 19th Floor, New York, New York 10016.

www.hmhco.com

Cover art © 2008 by Larry Rostant

Cover design by Sharismar Rodriguez

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data for individual titles is on file.

ISBN 978-0-544-85452-9

eISBN 978-0-547-88083-9

v4.0516

TO EVERYONE WHO ENJOYS GHOST STORIES

1

One rainy Sunday in March, I opened a box of books Mom had brought home from Grandmother’s house. Although Grandmother had been dead for five years, no one had unpacked any of the boxes. They’d been sitting in the attic collecting dust, their contents a mystery.

Hoping to find something to read, I started pulling out books—Charlie and the Chocolate Factory, Misty of Chincoteague, and at least a dozen Nancy Drew mysteries. At thirteen, I’d long since outgrown Carolyn Keene’s plots, but I opened one at random, The Bungalow Mystery, and began flipping the pages, laughing at the corny descriptions: “Nancy, blue eyed, and with reddish glints in her blonde hair,” “Helen Corning, dark-haired and petite.” The two girls were in a small motorboat on a lake, a storm was coming, and soon they were in big trouble. Just as I was actually getting interested in the plot, I turned a page and found a real-life mystery: a torn photograph.

In faded shades of yellow and green, Mom’s older sister, Dulcie, grinned into the camera, her teeth big in her narrow face, her hair a tangled mop of tawny curls. Next to her, Mom looked off to the side, her long straight hair drawn back in a ponytail, eyes downcast, unsmiling, clearly unhappy. Dulcie was about eleven, I guessed, and Mom nine or ten. Behind the girls was water—a lake, I assumed.

Pressed against Dulcie’s other side, I could make out an arm, a shoulder, and a few strands of long hair, just enough for me to know it was a girl. The rest of her had been torn away.

I turned the photo over, hoping to find the girl’s name written on the back. There was Grandmother’s neat, schoolteacherly handwriting: “Gull Cottage, 1977. Dulcie, Claire, and T—.”

Like her face, the rest of the girl’s name was missing.

Alone in the attic, I stared at the arm and shoulder. T . . . Tanya, Tonia, Traci, Terri. So many T names to choose from. Which was hers?

Putting the photo back in the book, I ran downstairs to ask Mom about Gull Cottage, the lake, and the girl. I found her in the kitchen chopping onions for the vegetable casserole she was fixing for dinner. Standing there, head down, she wore the same expression caught in the photograph. Not surprising. She always looked sad, even when she wasn’t.

I waved the photograph. “Look what I found—a picture of you and Dulcie at a lake somewhere. And another girl—”

Mom snatched the photograph, her face suddenly flushed. “Where did you get this?” She acted as if I’d been rummaging through her purse, her bureau drawers, the medicine cabinet, looking for secrets.

I backed away, startled by her reaction. “It fell out of your old book.” I held up The Bungalow Mystery. “It was in one of those boxes you brought back from Grandmother’s house. Look, here’s your name.” I pointed to “Claire Thornton, 1977,” written in a childish scrawl on the inside cover.

Mom stared at the photograph as if I hadn’t spoken. “I was sure I’d thrown this away.”

“Who’s the girl sitting beside Dulcie?” I asked, unable to restrain my curiosity.

“Me,” Mom said without raising her eyes.

“No, I mean on the other side, where it’s ripped.” I pointed. “See her arm and her shoulder? On the back Grandmother wrote T but the rest of her name was on the torn part.”

“I don’t remember another girl.” Mom gripped the photo and shook her head. “At the lake, it was always Dulcie and me, just Dulcie and me. Nobody else.”

At that moment, Dad came through the kitchen door and set a grocery bag on the counter. “Salad stuff,” he said. “They didn’t have field greens, so I got baby spinach.”

“Fine,” Mom said.

“What are you looking at?” Reaching over Mom’s shoulder, he took the photo. “Little Claire and little Dulcie,” he said with a smile. “What a cute pair you were. Too bad the picture’s torn—and the color’s so awful.”

Mom reached for the photo, but Dad wasn’t finished with it.

“This must have been taken in Maine,” he said.

“Yes.” She reached for the picture again.

“Hey, look at this.” Dad handed her the photo. “There’s another girl sitting next to Dulcie. See her arm? Who was she?”

“This picture was taken thirty years ago,” she said sharply. “I have no idea who that girl was.”

Slipping the photo into her pocket, Mom went to the kitchen window and gazed at the backyard, which was just beginning to show green after the winter. With her back to us, she said, “Soon it’ll be time to mulch the garden.”

It was her way of ending the conversation, but Dad chose to ignore the hint. “Your mom and aunt spent their vacations at Sycamore Lake when they were little,” he told me. “They still own Gull Cottage, but neither one of them has gone there since they were kids.”

“Why not?” I asked. “A cottage on a lake . . . I’d love to see it.”

“Don’t be ridiculous,” Mom said, her back still turned. “The place has probably fallen to pieces by now.”

“Why not drive up and take a look this summer?” Dad asked her. “Ali would love Maine—great hiking, swimming, canoeing, and fishing. Lobster, clams, blueberries. We haven’t had a real vacation for years.”

Mom spun around to face us, her body tense, her voice shrill. “I hated going there wh

en I was little. The lake was cold and deep and scary, and the shore was so stony, it hurt my feet. It rained for weeks straight. Thunder, lightning, wind, fog. The gnats and mosquitoes were vicious. Dulcie and I fought all the time. I never want to see Gull Cottage again. And neither does Dulcie.”

“Oh, come on, Claire,” Dad said, laughing. “It couldn’t have been that bad.”

“You don’t know anything about it.” Pressing her fingers to her temples, a sure sign of a headache, she left the room and ran upstairs. A second later, the bedroom door slammed shut.

I turned to Dad, frustrated. “What’s the matter with Mom now?”

“Go easy on her, Ali. You know how easily she gets upset.” He sighed and headed toward the stairs. “Don’t you have a math test tomorrow?”

Alone in the kitchen, I opened my textbook and stared at a page of algebra problems. Go easy on your mother, don’t upset her, she can’t handle it. How often had I heard that? My mother was fragile. She worried, she cried easily, sometimes she stayed in bed for days with migraine headaches.

From the room overhead I could hear the drone of my parents’ voices. Mom’s voice rose sharp and tearful. “I’ve told you before, I don’t want to talk about it.”

Dad mumbled something. I closed my algebra book and retreated to the family room. With the TV on, I couldn’t hear them arguing, but even a rerun of Law and Order couldn’t keep me from thinking about the photo. I certainly hadn’t meant to start a scene—I just wanted to know who “T” was.

I never saw the photo again. No one mentioned Sycamore Lake or Gull Cottage. But the more we didn’t talk about it, the more I thought about it. Who was “T”? Why didn’t Mom remember her? If Grandmother had still been alive, I swear I would’ve called her and asked who “T” was.

I thought about calling Dulcie and asking her, but if Mom saw the number on the phone bill, she’d want to know why I’d called my aunt and what we’d talked about. Mom had “issues with Dulcie”—her words. They couldn’t be together for more than a few hours without arguing. Politics, child raising, marriage—they didn’t agree on anything.

Maybe because I couldn’t talk to anyone about the photo, I began dreaming about “T” and the lake. Week after week, the same dream, over and over and over again.

I’m walking along the shore of Sycamore Lake in a thick fog. I see a girl coming toward me. I can’t make out her face, but somehow I know it’s “T.” She seems to know me, too. She says, “You’d better do something about this.” She points at three girls in a canoe, paddling out onto the lake. One is my mother, one is Dulcie, and I think the third girl is “T.” But how can that be? Isn’t she standing a few feet away? No, she’s gone. The canoe vanishes into the fog.

That’s when I always woke up. Scared, shivering—the way people feel when they say, “Someone’s walking on my grave.”

I wanted to tell Mom about the dream, but I knew it would upset her. Although Dad didn’t agree, it seemed to me she’d been more nervous and anxious since I’d shown her the photograph. She started seeing her therapist again, not once but twice a week. Her headaches came more frequently, and she spent days lying on the couch reading poetry, mainly Emily Dickinson—not a good choice in my opinion for a depressed person. Dickinson’s poems were full of things I didn’t quite understand but that frightened me. Her mind was haunted, I thought, by death and sorrow and uncertainty. Sometimes I suspected that’s why Mom liked Dickinson—they were kindred spirits.

Except for my dream and Mom’s days on the couch, life went on pretty much as usual. Dad taught his math classes at the university, graded exams, gave lectures, and complained about lazy students and boring faculty meetings—standard stuff. I got involved in painting scenery for the school play and doing things with my friends. As the weather warmed, Mom cheered up a bit and went to work in her flower garden, mulching, transplanting, choosing new plants at the nursery—the best therapy, she claimed.

And then Dulcie paid us an unexpected visit and threw everything off track.

2

One afternoon in May, I came home from school and found Dulcie and Emma in the living room with Mom. My heart gave a little dance at the sight of my aunt’s tall, skinny figure, her fashionably baggy linen overalls, the familiar mop of long tawny curls, the rings on her fingers. Right down to her chunky sandals and crimson toenails, she looked like what she was—an artist.

“Ali!” Dulcie jumped to her feet and crossed the room to hug me. “It’s great to see you.”

“You, too.” I hugged her tightly and breathed in the musky scent of her perfume.

Holding me at arm’s length, she gave me a quick once-over. Her silver bracelets jingled. “Look at you—a teenager already.” She turned to Mom with a smile. “They grow up so fast!”

“She’s only thirteen,” Mom murmured. “Don’t rush things.”

Dulcie frowned as if she might start arguing about how grown up I was. Before she could say anything, though, Emma flung herself at me. “Ali, Ali, Ali!”

“Whoa,” I laughed. “You’re getting so big, you’ll knock me down! Look at your hair—it’s almost as long as mine.”

Emma giggled and hugged me. “That’s ’cause I’m almost five. Soon I’ll be as big as you.”

Keeping an arm around my cousin’s shoulders, I turned back to Dulcie. “Are you in town for a show or—”

“I had to see the owner of a gallery in D.C. She wants to exhibit my work in a group show next fall, and I need peace and quiet to paint, so . . .” Dulcie glanced at Mom who sighed and shook her head, obviously worried about something.

“Your mother thinks this is the worst idea I’ve ever had,” Dulcie went on with a laugh. “But I’m going to fix up the old cottage at the lake and spend the summer there.”

I stared at her, hardly daring to believe she was serious. Sycamore Lake, the place that had obsessed me for two months now. Before I could bombard her with questions, Mom said, “Dulcie, I really think—”

“No arguments. My mind’s made up.” Dulcie smiled at Mom and turned to me. “I need a babysitter to entertain Emma while I paint. I’m trying to talk your mom into letting me borrow you for the summer.”

“Me?” My face flushed. “I’d love to baby-sit Emma at the lake! I’ve wanted to see it for ages. I found a—”

“Ali,” Mom interrupted. “I told you what it’s like there. Rain and mosquitoes and cold, gloomy days. Nothing to do. Nowhere to go. You’ll hate it.”

“Don’t believe a word of it,” Dulcie told me. “Sure, it’s cold and rainy sometimes. It’s Maine—what do you expect? But there’s plenty of sunshine. The mosquitoes aren’t worse than anyplace else. The lake’s—”

“The lake’s deep . . . and dark . . . and dangerous,” Mom cut in, choosing her words slowly and deliberately. “People drown there every summer.”

Dulcie frowned at Mom. “Do you have to be so negative about everything?”

To keep Mom from starting a scene, I jumped into the conversation.

“I’ve taken swimming lessons since I was six years old. I know all about water safety. I’d never do anything stupid.”

“Please, Aunt Claire, please, please, please!” Emma begged. “I want Ali to be my babysitter.” She hopped back and forth from one foot to the other, staring hopefully at Mom.

Say yes, I begged silently, say yes. My best friend, Staci, was going away, and a boring summer stretched ahead. I loved Emma, and I loved my aunt. A few months at the lake would be perfect.

Ignoring my pleading look, Mom shook her head. “I can’t possibly make a decision until Pete comes home from work. Ali’s his daughter, too. We have to agree on what’s best for her.”

Dulcie dropped onto the sofa beside Mom. “Sorry. I’m used to making my own decisions about Emma.” Tossing her hair to the side, she grinned at me. “It’s one of the many advantages of being divorced.”

“I didn’t mean—” Mom said.

“How about some coffee?” Dulcie aske

d, quickly diverting Mom. “And some fruit juice for Emma?”

“Of course.” Mom got up and headed for the kitchen with Dulcie behind her. I trailed after them, but at the doorway, my aunt turned and smiled at me. “Why don’t you read to Emma, sweetie? She put some of her favorite books in my bag.”

Secrets, I thought. Things they don’t want me to know about. I was tempted to follow them into the kitchen anyway, but it occurred to me that Dulcie might have better luck talking to Mom without my being there listening to every word.

Emma rummaged through her mother’s big straw bag and pulled out The Lonely Doll, a book I’d enjoyed when I was little.

“I like when Edith meets the bears, and she isn’t lonely anymore.” Emma climbed into my lap and rested her head against my shoulder.

“I like that part, too.”

Emma opened the book to a photo of Edith looking sad and lonely. “Someday I’ll have a friend,” she said. “And then I won’t be lonely anymore.”

“Silly,” I said. “You must have friends. Everyone has friends.”

She shook her head. “Not in New York. Everybody I know there is grown up. And grownups can’t be your friends.”

“Can I be your friend? Or am I too old?”

Emma gave me a solemn, considering look. “It would be better if you were five or six or even seven,” she said, “but I guess you can be sort of a friend.”

“Thank you, Princess Emma.” I gave her a little tickle in the side. “I’m greatly honored by your majesty’s decision.”

She giggled. “Will you read now?”

When we were about halfway through the story, we were distracted by rising voices in the kitchen.

“We’re adults now,” Mom was saying. “I don’t have to do everything you say. Ali’s my daughter. I’ll raise her the way I see fit!”

“It must be nice to own a child,” Dulcie replied.

“‘Own a child’? What’s that supposed to mean?”

“You’re so overprotective, you might as well keep her on a leash. Sit, Ali. Heel, Ali. Roll over, Ali.”

“How can you say that?” Mom’s voice rose. “I love Ali and I want her to be safe. She’s not going to spend the summer running wild, swimming, going out in boats—”

Mister Death's Blue-Eyed Girls

Mister Death's Blue-Eyed Girls The Ghost of Crutchfield Hall

The Ghost of Crutchfield Hall Hear the Wind Blow

Hear the Wind Blow Time of the Witch

Time of the Witch The Girl in the Locked Room: A Ghost Story

The Girl in the Locked Room: A Ghost Story All the Lovely Bad Ones

All the Lovely Bad Ones One for Sorrow

One for Sorrow Deep and Dark and Dangerous

Deep and Dark and Dangerous Tallahassee Higgins

Tallahassee Higgins Promises to the Dead

Promises to the Dead Took: A Ghost Story

Took: A Ghost Story Following My Own Footsteps

Following My Own Footsteps Wait Till Helen Comes: A Ghost Story

Wait Till Helen Comes: A Ghost Story Where I Belong

Where I Belong The Spanish Kidnapping Disaster

The Spanish Kidnapping Disaster Look for Me by Moonlight

Look for Me by Moonlight The Old Willis Place

The Old Willis Place Closed for the Season

Closed for the Season As Ever, Gordy

As Ever, Gordy Anna on the Farm

Anna on the Farm The Doll in the Garden

The Doll in the Garden Daphne's Book

Daphne's Book Witch Catcher

Witch Catcher The Gentleman Outlaw and Me--Eli

The Gentleman Outlaw and Me--Eli Wait Till Helen Comes

Wait Till Helen Comes Took

Took A Haunting Collection

A Haunting Collection Anna All Year Round

Anna All Year Round The Girl in the Locked Room

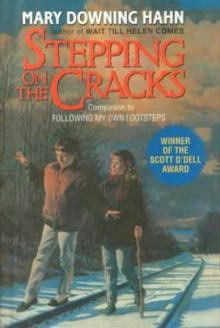

The Girl in the Locked Room Stepping on the Cracks

Stepping on the Cracks