- Home

- Mary Downing Hahn

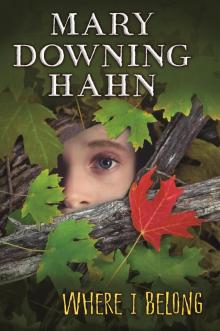

Where I Belong

Where I Belong Read online

Table of Contents

Title Page

Table of Contents

Copyright

Dedication

Epigraph

One

Two

Three

Four

Five

Six

Seven

Eight

Nine

Ten

Eleven

Twelve

Thirteen

Fourteen

Fifteen

Sixteen

Seventeen

Eighteen

Nineteen

Sample Chapter from THE GHOST OF CRUTCHFIELD HALL

Buy the Book

Read More from Mary Downing Hahn

About the Author

Clarion Books

215 Park Avenue South, New York, New York 10003

Copyright © 2014 by Mary Downing Hahn

All rights reserved.

For information about permission to reproduce selections from this book, write to Permissions, Houghton Mifflin Harcourt Publishing Company, 215 Park Avenue South, New York, New York 10003.

Clarion Books is an imprint of Houghton Mifflin Harcourt Publishing Company.

www.hmhco.com

The Library of Congress has cataloged the print edition as follows:

Hahn, Mary Downing.

Where I belong / by Mary Downing Hahn.

pages cm

Summary: “Eleven-year-old Brendan Doyle doesn’t get along with his foster mother, he’s failing sixth grade, and he’s bullied mercilessly by a band of boys in his class. Then Brendan meets two potential friends—an eccentric old man and a girl from summer school—and he sees that there may be hope for him after all.”—Provided by publisher.

ISBN 978-0-544-23020-0 (hardcover)

[1. Conduct of life—Fiction. 2. Green Man (Tale)—Fiction. 3. Foster home care—Fiction. 4. Friendship—Fiction. 5. Bullies—Fiction. 6. Schools—Fiction. 7. Eccentrics and eccentricities—Fiction.] I. Title.

PZ7.H1256Whe 2014

[Fic]—dc23

2013043881

eISBN 978-0-544-37428-7

v1.0914

For nemophilists everywhere*

*Those who love the woods

We could never have loved the earth so well

if we had had no childhood in it.

George Eliot,

The Mill on the Floss

ONE

I’M SITTING AT MY DESK, drawing on the back of my math worksheet, not even trying to solve the problems today. What’s the use? They’ll all be wrong, and Mrs. Funkhauser will make some sarcastic comment about my inability to learn long division—as if I cared about something as useless as long division, which has no value in my opinion except to sort stupid kids from smart ones, and you know where that puts me. Stupid. Stupid. Stupid.

If our classroom had windows, I could watch the sky and the clouds and the trees, maybe a few birds flying past on their way to someplace where there’s no math, but when my school was built they wanted something called open space. No walls between rooms. Just chest-high bookcases to divide kids up into what they call pods, which makes us all baby whales, I guess.

No windows, either—only skylights in the ceiling. You can’t look outside unless you want to sprain your neck watching clouds.

Open space—how could there ever be such a thing in a school where all the spaces are closed off and you are trapped inside until you are sixteen and then maybe, just maybe, you will be free but everyone says no, you will be working in McDonald’s if you don’t go to college? Four more years after thirteen years of public school only with professors (what do they profess?) and majors and minors, which sounds like the army to me.

Anyway, why am I worrying about college? I’m not smart enough to go. What college would take a kid who can’t even add and subtract? A kid who—

That’s when I hear Mrs. Funkhauser say, “Time’s up, boys and girls. Hand in your math sheets.”

I look at the picture I’ve drawn of the Green Man. I just learned about him in a book of British myths and legends. He dwells deep in the woods and is seldom seen, partly because his face is almost hidden by clusters of oak leaves that seem to grow from his skin and sprout from his mouth. He protects the forest and all that dwell there—animals, birds, and trees. Those who respect the natural world need not fear him, but those who harm the forest will feel his wrath. Like a superhero, he fears nothing. He is just. And powerful.

My Green Man is treetop tall. He carries a sword. His beard is long and thick, his mustache curls, and his face is framed with oak leaves. His wavy hair falls to his shoulders like mine. It’s the best picture I’ve ever drawn, and I don’t want Mrs. Funkhauser to see it. I begin to slide it quietly under my notebook.

Suddenly she’s beside me. “Where is your math sheet, Brendan?” The heat of her anger scorches my skin.

I don’t say anything. I stare at my desk. The back of my neck feels like it’s on fire.

The giggling starts. It’s almost time to go home. The whales are restless. They’re hoping for a last-minute Funkhauser vs. Brendan show, a high note to end the boring day.

“What’s this?” Mrs. Funkhauser’s eyes are eagle sharp. They see everything, even the corner of my math sheet sticking out from my notebook. With one quick move, her talons jerk my paper from its hiding place. She looks at the problems. “You haven’t even tried, Brendan. What have you been doing all this time?”

I keep my head down and say nothing. Please don’t look at the back of my paper. Please don’t tear up my picture.

But of course she turns my paper over. She pauses to increase suspense. The whales squirm in their seats, ready to be entertained. Where’s the popcorn? Who’s got the soda?

Mrs. Funkhauser holds my drawing up for the whales to see. “Boys and girls,” she says, “look at this. Brendan Doyle thinks drawing pictures is more important than math.”

I know drawing is more important than math, but I sit there, head down, silent, waiting for the bell to ring, braced to run out the door faster than the whales. If they catch me, I’ll need the magic sword I haven’t got.

The whales laugh and Mrs. Funkhauser smiles at them—they’re smart, they know what’s important. They’ve learned their multiplication and long division, their fractions and ratios and decimals. They hand in their homework on time, neatly done, they follow directions, they pay attention. If they have to work at McDonald’s, they will always remember to say, “Do you want fries with that?” and “Have a nice day.” Their parents are proud of them. No one thinks they’re weird.

Mrs. Funkhauser crumples my drawing into a small wad of paper. My heart crumples too. But I don’t look up and I don’t say anything. I pretend Mrs. Funkhauser is being eaten by a dragon while the Green Man looks the other way. Saving her would be a waste of time.

Mrs. Funkhauser sighs. “What am I going to do with you, Brendan?”

I shrug. I don’t know what to do with me. Or her. Or anyone else.

“Why won’t you do your work? How do you expect to succeed in life?”

The whales laugh. What a joke. Me succeed in life? Hah-hah.

“Get that hair out of your face. Look at me when I’m talking to you!”

When I don’t move, Mrs. Funkhauser lifts my chin and forces me to look at her. “You’ll never get anywhere in this world unless you change your attitude and learn to cooperate. The way you’re going, you won’t pass sixth grade.”

As if I care. I’ve slid through every grade since I started school. I pass only because I read so well, not because I do my work. Besides, I hear it’s bad to flunk a kid, because you’ll damage his self-esteem. Maybe Mrs. Funkhauser has figured out I have no self-esteem

to damage.

“Are you listening to me? Do you want to repeat sixth grade?”

I shrug. I want to say Yes. So I won’t have to go to middle school, I can stay right here. But not in your class. In someone else’s class where the teacher and all the kids will soon grow to hate me.

The dismissal bell interrupts Mrs. Funkhauser. I leap from my seat and run. The first kid out the door, that’s me. Down the steps, across the street, getting a head start. Behind me, I hear Jon Owens shout, “Run, Brenda, run!”

He and his friends chase me for maybe a block, calling me a girl, a weirdo, a long-haired freak, but they can’t catch me. I’m the fastest runner in school, mainly because I’ve had a lot of practice eluding Jon.

From the day I walked into Mrs. Funkhauser’s classroom, he and the other kids have hated me because of my hair and my attitude. Weird is what they call me. Weird is what I am. I don’t belong anywhere and I don’t care. I might be only twelve years old, but I know you can’t trust anyone. Sooner or later, they’ll desert you, betray you, turn against you, and you’ll end up alone. If a foster kid learns anything after moving from house to house and school to school, it’s Don’t even try to make friends.

Even though I no longer hear Jon and his friends behind me, I don’t slow down. Somehow I’ve ended up in the old part of town, in a bad neighborhood, on a street of big houses chopped up into apartments. Gang tags and graffiti cover street signs and stop signs, telephone poles, walls, and fences. Men linger in groups on corners. Women sit on porch steps, smoking and keeping an eye on their kids. Broken-down cars with their hoods up are parked along the street.

I definitely don’t belong here, so I keep running, taking care not to look at anyone in case I offend them. Heading toward Main Street, I cut through an out-of business convenience store’s parking lot. That’s when I make a major mistake. I look back to make sure nobody’s following me and run right into a big Harley Davidson bike parked behind the boarded-up store. It falls over with the loud noise of metal crashing onto asphalt. I fall with it, cutting my hand on broken glass. Scrambling to my feet, I see the owner of the bike running toward me, cursing.

I groan with despair. I’ve knocked over Sean Barnes’s bike and I’m done for. Shouting a useless apology, I turn to run, but I’m not fast enough. Sean grabs a handful of my hair in his fist and jerks me to a stop. My eyes water with pain.

“I’m sorry, I’m sorry, I didn’t see it, I didn’t mean to,” I babble in a high voice.

He doesn’t let go of my hair. “You know who I am?”

My mouth is dry with fear, but I manage to nod. Everybody in East Bedford knows who Sean Barnes and his friends are. They’ve all been in and out of juvenile detention since they were my age, maybe even younger. They get into knife fights, they break into houses, they deal drugs in the dark corners of the McDonald’s parking lot. Kids say they run a meth lab in an abandoned factory out on Muncaster Road. Everybody is scared of them, even grownups. To hear people talk, they’re responsible for every crime in town.

Just last night, Mrs. Clancy, my foster so-called mother, read the local paper’s crime log out loud. “Jewelry store in the mall robbed, three houses broken into, car stolen, homeless man assaulted in town park,” she says, “all by person or persons unknown—Sean Barnes, in other words. He should be locked up. Not out walking the streets, stealing cars and beating up helpless old men. I won’t go near that park. Even in the middle of the day, it’s not safe.”

And now here I am in a deserted parking lot behind a boarded-up store. Not a person in sight, and even if there were they’d look the other way. Sean has a tight grip on my hair, and two of his friends have joined him. I know their names too—Gene Cooper and T.J. Wasileski—as big and mean and scary as Sean. They’re both grinning at the sight of me, their day’s entertainment, the star of the show.

“What do you mean knocking my bike over, you screwed-up little punk?” Sean shoves his face close to mine and breathes cigarettes and beer in my face. His teeth are yellow. He has acne scars. And sleeve tattoos on both arms. “You need a haircut real bad,” he says. “You look like a girl. But a whole lot uglier.”

I try to yank free, but he holds tight to my hair. “You got a gender problem or something?”

“We can help him with that,” T.J. says. “One flick of a knife and he becomes a she.”

Wrapping my hair around his fist, Sean shoves me down on the asphalt so I’m face to face with the Harley. “See these scratches?” He yanks my hair hard. My nose bangs against the bike’s wheel. “See where the paint’s chipped? You did that, you little freak.”

“I didn’t mean to knock your bike over.”

“Is that all you got to say?” T.J. nudges me hard with the toe of his boot and my nose hits the wheel again. Blood drips and spatters on the asphalt.

Still gripping my hair, Sean yanks me to my feet. “Ah, look, ugly girl’s nose is bleeding. And he’s crying.”

“You owe Sean some respect.” Gene kicks my feet out from under me, and for a painful second I hang by my hair.

Sean opens his fist and lets me fall. I start to get up, but he pushes me down. “Stay on your knees and apologize.”

“I’m sorry,” I mutter. “I didn’t see the bike. It was an accident.”

“Maybe his hair was in his eyes,” T.J. says. “Want I should chop it off?” He flourishes a hunting knife. The sunlight bounces off the blade like sparks of fire. I’m so scared, my insides are melting.

Sean pulls me up and shoves me toward T.J. T.J. shoves me toward Gene, Gene shoves me back to Sean. They’re laughing, but each time they push me they push harder. Round and round I go between the three of them, faster and faster. I’m dizzy, I stagger, almost fall but they catch me and keep up the game.

Then, as quickly as it began, it ends. Sean lets me fall and stands there looking down at me. The sun is in my eyes and I can’t see his face. He reaches into his pocket and I flinch, expecting to see a knife. He pulls out a pack of cigarettes instead and lights one, flicking the match at me.

“Girl,” he sneers. “Messed-up long-haired freak. Something like this happens again, I’ll give you more than a bloody nose.”

The three of them get on their bikes and roar away, laughing. I scramble to my feet. The parking lot is empty, they’re gone, and all that’s left is my sore scalp, still burning.

TWO

I’M IN AN UNFAMILIAR PART OF TOWN, running blindly, too scared to slow down. I cut corners, dash through alleys, jump a fence, and scoot across a yard. Dogs bark at me. A horn blows and a car brakes to miss hitting me. A kid on a bike yells, “Watch where you’re going!”

I finally come to a stop at the end of a road and stand there, gasping for breath, and wait for my heart to settle down. At the bottom of a hill, train tracks curve into the woods. I know where I am now. If I follow those tracks, I’ll be home in less than half an hour.

I look down at myself. My shirt is stained with blood from my nose, and the knee of my jeans is ripped. Mrs. Clancy will be upset. She’ll want to know what happened, who hit me and why. Soon she’ll say, Why can’t you get along in school, why can’t you be like other boys, if you’d just try to fit in, get that hair cut, improve your attitude, do your schoolwork, join Little League . . .

She’ll make me eat dinner and then, after I go to bed, I’ll be awake all night with a bellyache. My stomach twists just thinking about it.

If only I had someplace to go besides home. A safe place where I’d belong and nobody would call me names or beat me up or laugh at me. No school. No teachers. No mean kids. No Mrs. Clancy. Just me, Brendan Doyle.

Across the railroad tracks, the tall trees sway in a breeze. They have new leaves, more gold than green. They sigh and whisper to themselves.

Mrs. Clancy has told me drug users, drunks, and perverts hang out in the woods. “You go down there by yourself, you might never come out. You’d get lost and no one would find you for years. Those woods are part of a nation

al forest. They stretch from here to Tennessee. No telling what’s hiding there.”

But today I see the woods as a sanctuary.

I make my way slowly down the embankment, slipping and sliding on cinders. I look both ways. No train in sight. I run across the tracks.

Safe on the other side, I pause. Sunlight behind me, dark shade ahead of me. A branch snaps as if something stepped on it. Birds sing in hidden places. A crow caws and another answers. A breeze springs up and quivers through the leaves. Light dances from tree to tree, splashing the foliage with gold.

My skin prickles. This is a magic place, the sort of forest the Green Man might call home. I can almost feel him watching me from the trees, wondering what sort of boy I am. Will I harm the forest or be its friend?

Taking care to move slowly, I tiptoe so as not to disturb the deep silence of the watchful trees. Here and there boulders and rocks, mossy and splotched with lichens, rise from beds of fern. Trolls taken by surprise, I think, changed to stone forever.

The trees close in behind me, and I can no longer see the light at the edge of the woods. Just shafts of sunshine lancing through the branches. It’s like being in a cathedral—at least how I guess it might be. I’ve never been in a cathedral. Never even seen one except in pictures. But the forest has the same sort of silence and the tree trunks are tall and straight like stone columns and there’s a kind of holiness here that makes you walk softly and whisper.

The snap of a twig frightens me, and I look over my shoulder. Nothing to see except leaves and shadows, but that doesn’t mean nothing’s there. It could be the Green Man himself, following the trespasser in his woods.

Maybe I should turn around and go home, but I didn’t follow a path. There is no path. Am I lost already? I stand there, unsure what to do.

Mister Death's Blue-Eyed Girls

Mister Death's Blue-Eyed Girls The Ghost of Crutchfield Hall

The Ghost of Crutchfield Hall Hear the Wind Blow

Hear the Wind Blow Time of the Witch

Time of the Witch The Girl in the Locked Room: A Ghost Story

The Girl in the Locked Room: A Ghost Story All the Lovely Bad Ones

All the Lovely Bad Ones One for Sorrow

One for Sorrow Deep and Dark and Dangerous

Deep and Dark and Dangerous Tallahassee Higgins

Tallahassee Higgins Promises to the Dead

Promises to the Dead Took: A Ghost Story

Took: A Ghost Story Following My Own Footsteps

Following My Own Footsteps Wait Till Helen Comes: A Ghost Story

Wait Till Helen Comes: A Ghost Story Where I Belong

Where I Belong The Spanish Kidnapping Disaster

The Spanish Kidnapping Disaster Look for Me by Moonlight

Look for Me by Moonlight The Old Willis Place

The Old Willis Place Closed for the Season

Closed for the Season As Ever, Gordy

As Ever, Gordy Anna on the Farm

Anna on the Farm The Doll in the Garden

The Doll in the Garden Daphne's Book

Daphne's Book Witch Catcher

Witch Catcher The Gentleman Outlaw and Me--Eli

The Gentleman Outlaw and Me--Eli Wait Till Helen Comes

Wait Till Helen Comes Took

Took A Haunting Collection

A Haunting Collection Anna All Year Round

Anna All Year Round The Girl in the Locked Room

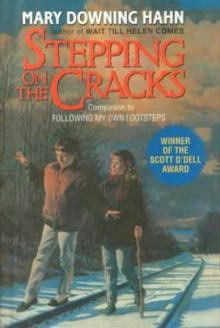

The Girl in the Locked Room Stepping on the Cracks

Stepping on the Cracks