- Home

- Mary Downing Hahn

One for Sorrow

One for Sorrow Read online

Contents

* * *

Title Page

Contents

Copyright

Dedication

One

Two

Three

Four

Five

Six

Seven

Eight

Nine

Ten

Eleven

Twelve

Thirteen

Fourteen

Fifteen

Sixteen

Seventeen

Eighteen

Nineteen

Twenty

Twenty-One

Twenty-Two

Twenty-Three

Twenty-Four

Twenty-Five

Counting Crows

Afterword

Read More from Mary Downing Hahn

Singular Reads

About the Author

Connect with HMH on Social Media

Clarion Books

3 Park Avenue

New York, New York 10016

Copyright © 2017 by Mary Downing Hahn

All rights reserved. For information about permission to reproduce selections from this book, write to [email protected] or to Permissions, Houghton Mifflin Harcourt Publishing Company, 3 Park Avenue, 19th Floor, New York, New York 10016.

Clarion Books is an imprint of Houghton Mifflin Harcourt Publishing Company.

www.hmhco.com

Cover photographs © 2017 by Richard Nixon/Trevillion Images (cemetery); Larry Rostant (girl)

Cover design by Christine Kettner

The Library of Congress has cataloged the print edition as follows:

Names: Hahn, Mary Downing, author.

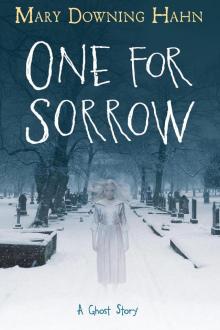

Title: One for sorrow : a ghost story / Mary Downing Hahn.

Description: Boston ; New York : Clarion Books, Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, [2017] | Summary: “When unlikeable Elsie dies in the influenza pandemic of 1918, she comes back to haunt Annie to make sure she’ll be Annie’s best—and only—friend soon”—Provided by publisher.

Identifiers: LCCN 2016010761 | ISBN 9780544818095 (hardcover)

Subjects: | CYAC: Best friends—Fiction. | Friendship—Fiction. | Ghosts—Fiction. | Influenza Epidemic, 1918–1919—Fiction. | World War, 1914–1918—United States—Fiction. | Horror stories.

Classification: LCC PZ7.H1256 On 2017 | DDC [Fic]—dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2016010761

eISBN 978-1-328-69902-2

v1.0617

Dedication

James Cross Giblin

July 8, 1933–April 10, 2016

This book is dedicated to the memory of my beloved editor, mentor, and friend for over thirty years.

Thank you, Jim, for your patience, kindness, and generosity and for all you’ve taught me about writing—and rewriting. I wish this were not the last of our joint efforts.

One

LTHOUGH I DIDN’T REALIZE IT, my troubles began when we moved to Portman Street, and I became a student in the Pearce Academy for Girls, the finest school in the town of Mount Pleasant, according to Father. I was shy, maybe even a little timid, and I had no idea how to make friends. In my old town, there were three girls my age living in my neighborhood, and I didn’t remember making friends with them. We lived on the same street, and we were friends. It was as simple as that.

But no girls lived on my new street, so when I walked into class on a sunny September day, I didn’t know anyone. All I saw was a sea of white blouses, blue ties, and blue skirts. Row after row of them. I was too nervous to notice the faces, just the uniforms.

Miss Harrison introduced me. “Girls, it’s my pleasure to introduce Annie Browne, new to our school from the Fairfield Academy in Mount Holly. Please make her feel welcome in true Pearce fashion.”

I didn’t smile for fear no one would smile back. With my head down, I took my seat, folded my hands on my desktop, and stared at the stack of books Miss Harrison gave me. World Geography, the biggest and thickest, was on the bottom. Weighing it down were five more books—Sixth-Grade Arithmetic, Adventures in Reading Book II, Grammar Handbook, United States History, and A Girl’s Treasury of Poetry, as well as a penmanship workbook.

Miss Harrison began the morning exercises with the Lord’s Prayer, but before we began the Pledge of Allegiance, she said, “Let us say a prayer for our boys overseas. May God bring them home safely from this terrible war.”

We bowed our heads, and I prayed especially hard for Uncle Paul, Mother’s brother who was in France fighting the Germans. The newspapers were full of dreadful stories of trenches and poison gas and bombs and battles. I worried every day about my uncle. I wished President Wilson had never declared war, but Father said it was our duty to save Europe from Germany. I was glad he was too old to be drafted.

After we pledged allegiance to the flag, we took our seats and Miss Harrison pulled down a large map of the world and quizzed us about the war. Tapping her pointer on northeast France, she asked what was happening there. I wasn’t sure, so I lowered my head and prayed she wouldn’t call on me.

Plenty of hands shot into the air. Miss Harrison looked around the room and said, “Rosie O’Malley. Stand up and tell us what you know.”

A red-haired girl in the back row got to her feet. She had so many freckles you could hardly see her skin.

She grinned at the girl who sat beside her. “That’s the Argonne Forest,” she told Miss Harrison. “We’re fighting a big battle there against the dirty rotten Huns.”

Miss Harrison frowned. “Correct on location, Rosie, but I’ve told you before not to use slang. In this class, we speak formal English. Please repeat your answer, using appropriate terminology.”

Rosie shrugged. “All right. We’re fighting the dirty Germans in the Argonne Forest, and I hope we kill every one of them.”

A low giggle spread through the room, and Miss Harrison frowned again. “Just answer, Rosie, without the adjective and your opinions.”

Rosie’s face turned as red as her hair. “We’re fighting the Germans in the Argonne Forest, but we all know they’re dirty Huns. That’s what everybody calls them. Huns, Krauts, Fritz, swine—why can’t we say what they are?”

“You may use crude language when you are not in school, Rosie, but in this room you will speak formally. Please see me after school.”

Rolling up the map with a snap, Miss Harrison told us to open our arithmetic books. Instead of giggles, I heard soft moans. Whether it was sympathy for Rosie or dread of arithmetic, I couldn’t tell. Maybe both.

After a lesson on changing fractions to percentages, we diagrammed long complex sentences that used up a whole page in my notebook and took a spelling test. Not too hard; I only missed two words out of twenty—a solid B. Father would ask why I missed two, of course, but Mother would say there was nothing wrong with a B.

When Miss Harrison dismissed us for recess, I was happy to stretch my legs but worried about going outside to play with girls I didn’t know. I walked to the cloakroom slowly, hoping the others had already gotten their coats and rushed to the playground.

Only one girl remained. She had a pale, round face, and her blond hair was pulled tightly into French braids. She was taller than I was and heavier, not actually fat, but definitely not thin. When I reached for my sweater, she smiled at me, revealing a mouthful of the most crooked teeth I’d ever seen.

“My name is Elsie Schneider,” she said. “And we’re going to be friends, Annie Browne. I knew it when I saw you come through the door.”

She grabbed my hand. Her skin was cold and damp, and I wanted to snatch my hand away and wipe it on my skirt. But that would have been rude, so I let her hold it.

Elsie led me down

the empty hall. “There’s lots you need to know about this school,” she said. “Things I wish somebody had told me when I started here last year.”

“It seems nice,” I said. “As far as schools go,” I added so she wouldn’t think I was a goody-goody.

“Nice?” Elsie laughed. “Just wait. You’ll see. The girls here are all conceited snobs. They’ve already chosen who they want for friends. They didn’t choose me, and they won’t choose you, either.”

She squeezed my hand so hard it hurt and added, “But that’s all right because we have each other.”

Pushing open a door, she stopped on the top step. Below us, the girls in our class played tag, jumped rope, and gathered in laughing groups.

Of all the girls, Rosie laughed the loudest and talked the most. She was like a toy wound up too tight. She swung high and ran fast, and everyone followed her, doing what she did, and calling “Rosie, wait.” “Rosie, I’ll share my cookies with you if you sit next to me at lunch.” “No, sit next to me, and I’ll give you my cupcake, devil’s food with chocolate icing.” “Rosie, come to the sweet shop after school, and I’ll buy you a peppermint stick.”

Rosie never said yes or no. She laughed and kept going as if she was waiting for the best offer.

Elsie made a face. “And that girl, Rosie O’Malley, is the worst one of all. You saw how rude she was to Miss Harrison. She’s absolutely awful. I hate her. Don’t you?”

“I don’t even know her.” In my eyes, Rosie was exciting, a girl who did things and had lots of friends. She was much more interesting than Elsie, but I certainly wasn’t ready to say that and risk losing the only friend I’d made so far.

“Do you want to play hopscotch or swing or anything?” I asked Elsie. It seemed to me some of the girls had noticed us standing apart. A few whispered among themselves, looked at Elsie and me, and laughed. I didn’t like being stared at. I checked to see if my sweater was buttoned crooked. Maybe a shoelace was untied. Maybe my hair had a tangle Mother hadn’t seen or I had jam on my mouth.

In answer to my question, Elsie shook her head. “All the swings are taken. And I hate hopscotch, don’t you? It’s almost as stupid as jump rope and jacks. Baby stuff, I think.”

“Hopscotch is okay. You know, if there’s nothing else to do.” Here I was again, trying not to offend her. Why couldn’t I speak up and say I loved hopscotch? Like jump rope and jacks, I was good at it. My friends at my old school called me the hopscotch queen.

Elsie took my hand again. “Let’s walk together, Annie.”

Conscious of being watched, I let her hold my hand and lead me down the steps. A group of girls thronged around us. Rosie grabbed Elsie’s and my linked hands and held them up to show everyone.

“Look,” she shouted. “Fat Elsie has a girlfriend!”

I snatched my hand away, but Rosie and everyone else laughed. One of Rosie’s friends gave Elsie a little shove and looked at Rosie to see if she was impressed.

“Better not make Fat Elsie mad,” Rosie sneered. “She’ll tell Miss Harrison.”

Someone began a chant, and the others took it up.

Tattletale

ate a snail,

threw it up in the garbage pail.

Elsie pulled me away. “Come on, Annie. Those girls aren’t worth a wooden nickel. Who cares what they say? Not me.”

Trying to ignore the other girls, I walked away with Elsie. Whether or not she cared, I cared.

Elsie pulled me closer. “I hate Rosie so much,” she hissed in my ear. “Someday I’ll get even with her. Just wait. You’ll see.”

Behind us, the other girls chanted our names and laughed. “Elsie and Annie sitting in a tree, fat and ugly as they can be.”

When the bell rang, I was more than ready to join the line waiting to go back to our classroom. On my first day at Pearce, I’d made one friend and twenty enemies.

Elsie and I took a place at the back of the line. Ahead of us, the other girls giggled and jostled one another until Miss Harrison pulled a whistle out of her coat pocket and blew a warning blast.

Immediately the line straightened and everyone stopped giggling. Two by two, we walked quietly inside and took our seats without a sound. Everyone, that is, except Elsie. She stopped at Miss Harrison’s desk and whispered a few words. Miss Harrison picked up her pencil and wrote something down.

“You may take your seat now, Elsie,” Miss Harrison said without looking up.

“Yes, ma’am.” Shooting a sly look at Rosie, Elsie sashayed to her seat and grinned at me. The dirty looks directed to Elsie shifted to me. The other girls were holding me to blame for whatever Elsie told Miss Harrison.

“Tattletale, ate a snail,” someone whispered behind me. My face burned with shame. I’d never tattled on anyone, not once in my whole life. I’d rather have had my tongue torn out than tell. It wasn’t fair to lump me with Elsie. Those girls didn’t even know me.

“Before we open our readers,” Miss Harrison said, “I must tell you that I expect you to exhibit the same good behavior on the playground as you do in the classroom. I will not tolerate name calling or teasing.”

What had Elsie told Miss Harrison? Out of the corner of my eye, I saw Rosie make a face at Elsie, carefully shielding herself from Miss Harrison’s watchful eye. Someone giggled. Miss Harrison looked at Rosie, who sat with her hands folded primly on her desk.

The rest of the day passed slowly. When the dismissal bell finally rang, my first thought was to escape from Elsie, but she was by my side before I had buttoned my sweater.

As we left the classroom, Elsie paused in the doorway to take a quick look at Rosie, who was standing at the blackboard, her back to us, writing, I will use proper language in school. Her handwriting sloped upward and her letters were poorly formed, but maybe that was because she was in a hurry to finish.

“I hope Miss Harrison makes her write it five hundred times,” Elsie whispered.

Miss Harrison had ears as sharp as her eyes. She gave Elsie and me an angry look, clearly warning us we’d be writing on the blackboard ourselves if we didn’t leave at once. Rosie turned her head and made a face at us both.

Once more, I was being blamed along with Elsie for things I hadn’t done.

As we walked down the school steps—it was against the rules to run, according to Elsie—she said, “You know what I think?”

I shook my head.

“Miss Harrison should make Rosie write it five thousand times and then erase it and tell her to start all over again, using her best handwriting instead of that scribble scrabble she’s doing.”

Elsie smiled with so much glee I turned my head away. How was I to escape from her?

Two

HEN WE REACHED PORTMAN STREET, I said, “I live just around the corner.” Thinking I was rid of her at last, I started walking toward home, but to my disappointment, Elsie turned the corner with me.

“Do you live near here?” I crossed my fingers behind my back and hoped she’d say no.

“I live way across town, in the opposite direction.” She took my hand. “I thought we’d go to your house and play.”

I tried to think of a reason she couldn’t come home with me, but my mind was numb. So hand in hand, we walked up the front steps and went inside.

Mother was sitting on the couch reading a magazine. When she saw me, she smiled and got to her feet to give me a hug and a kiss. “How was school, darling?”

Before I could answer, Elsie said, “This awful girl named Rosie was mean to Annie. And the other girls ganged up on us. But Annie and I are best friends, and we don’t care what they say or do. We have each other.”

Mother looked at Elsie as if she hadn’t actually noticed her until she spoke up.

“This is Elsie Schneider,” I told her. “She’s in my class.”

Mother smiled at Elsie but immediately looked at me. With concern, she asked, “Whatever happened, Annie? You had plenty of friends in our old neighborhood.”

“Oh, but

Mrs. Browne, you don’t know the girls at Pearce,” Elsie butted in again. “They’re mean and conceited, and they do everything Rosie says. They like who she likes and hate everybody else.”

Mother turned to me. “Should I speak to Miss Harrison about this?”

“No,” I said, “please don’t. You’ll just make it worse.”

“They already think we’re tattletales,” Elsie put in.

“I was about to fix hot chocolate.” Mother spoke as if a treat might make Elsie and me feel better. “Would you two like some?”

“Oh, yes,” Elsie said. “Do you have cookies? I love vanilla wafers.”

We followed Mother to the kitchen. “You have such a pretty house,” Elsie told Mother. “It’s so comfortable and cozy.”

“Why, thank you.” Mother smiled at Elsie. “Aren’t you sweet?”

Elsie glanced at me, obviously pleased that Mother liked her.

Mother warmed milk and melted chocolate in the double boiler. Elsie watched her add sugar and butter.

As soon as Mother set steaming mugs and a plate of vanilla wafers on the table, Elsie reached for a cookie and stuffed it into her mouth as if she thought someone might slap her hand. She burned her tongue because she gulped a mouthful of hot chocolate before it cooled enough to drink. I noticed Mother watching Elsie as if she was wondering whether all the girls at Pearce behaved this way. If so, perhaps someone should teach them table manners.

“Elsie,” Mother said, “if you eat too many cookies, you won’t have room for dinner.”

Elsie merely shrugged and took another cookie. With her mouth full, she said, “I warned you I love vanilla wafers.”

When not a crumb remained and all the hot chocolate was gone, Elsie asked if we could play in my room for a while.

As she followed me upstairs, she caressed the oak banister. “I love the way this wood feels,” she said. “It’s so smooth. No splinters or chipped paint like my house.”

Mister Death's Blue-Eyed Girls

Mister Death's Blue-Eyed Girls The Ghost of Crutchfield Hall

The Ghost of Crutchfield Hall Hear the Wind Blow

Hear the Wind Blow Time of the Witch

Time of the Witch The Girl in the Locked Room: A Ghost Story

The Girl in the Locked Room: A Ghost Story All the Lovely Bad Ones

All the Lovely Bad Ones One for Sorrow

One for Sorrow Deep and Dark and Dangerous

Deep and Dark and Dangerous Tallahassee Higgins

Tallahassee Higgins Promises to the Dead

Promises to the Dead Took: A Ghost Story

Took: A Ghost Story Following My Own Footsteps

Following My Own Footsteps Wait Till Helen Comes: A Ghost Story

Wait Till Helen Comes: A Ghost Story Where I Belong

Where I Belong The Spanish Kidnapping Disaster

The Spanish Kidnapping Disaster Look for Me by Moonlight

Look for Me by Moonlight The Old Willis Place

The Old Willis Place Closed for the Season

Closed for the Season As Ever, Gordy

As Ever, Gordy Anna on the Farm

Anna on the Farm The Doll in the Garden

The Doll in the Garden Daphne's Book

Daphne's Book Witch Catcher

Witch Catcher The Gentleman Outlaw and Me--Eli

The Gentleman Outlaw and Me--Eli Wait Till Helen Comes

Wait Till Helen Comes Took

Took A Haunting Collection

A Haunting Collection Anna All Year Round

Anna All Year Round The Girl in the Locked Room

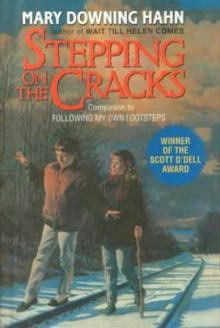

The Girl in the Locked Room Stepping on the Cracks

Stepping on the Cracks