- Home

- Mary Downing Hahn

The Ghost of Crutchfield Hall

The Ghost of Crutchfield Hall Read online

The Ghost of Crutchfield Hall

Mary Downing Hahn

Table of Contents

Title Page

Table of Contents

...

Copyright

Dedication

One

Two

Three

Four

Five

Six

Seven

Eight

Nine

Ten

Eleven

Twelve

Thirteen

Fourteen

CLARION · BOOKS

HOUGHTON MIFFLIN HARCOURT

BOSTON · NEW YORK 2010

CLARION BOOKS

215 Park Avenue South

New York, New York l0003

Copyright ©2010 by Mary Downing Hahn

The text of this book is set in 12.5-point Franklin Caslon.

Book design by Sharismar Rodriguez

All rights reserved. For information about permission to reproduce selections from

this book, write to Permissions, Houghton Mifflin Harcourt Publishing Company,

215 Park Avenue South, New York, New York 10003.

Clarion Books is an imprint of Houghton Mifflin Harcourt Publishing Company.

www.hmhbooks.com

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Hahn, Mary Downing.

The ghost of Crutchfield Hall / by Mary Downing Hahn.

p. cm.

Summary: In the nineteenth century, twelve-year-old Florence Crutchfield leaves a London

orphanage to live with her great-uncle, great-aunt, and sickly cousin James, but she soon

realizes the home has another resident, who means to do her and James harm.

ISBN 978-0-547-38560-0

[1. Orphans—Fiction. 2. Ghosts—Fiction. 3. Brothers and sisters—Fiction. 4. Jealousy—

Fiction. 5. Great Britain—History—Victoria, 1837–1901—Fiction.] I.Title.

PZ7.H1256Gho 2010

[Fic]—dc22

2009045351

Manufactured in the United States of America

DOC 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

4500237149

For my daughters, Kate and Beth,

who will always be my favorite readers

One

TAKE GOOD CARE OF THIS GIRL," Miss Beatty told the coachman. "She's an orphan, you know, and never set foot out of London. Make sure she gets where she's going safely."

After turning to me, Miss Beatty smoothed my hair and checked the note she'd pinned to my coat: "Mistress Florence Crutchfield," it read. "Bound for Crutchfield Hall, near Lower Bolton."

"Now, you behave yourself," she warned me. "Don't talk to strangers, no matter how nice they seem, sit still, and don't daydream. Keep your mind on what you're doing and where you're going." She paused and dabbed her eyes with her handkerchief.

"And when you get to your uncle's house..." She sniffed and went on, "Be a good girl. Do as you're bid. None of your mischief, or he'll be sending you back here."

Unable to restrain myself, I threw my arms around her. "I'll miss you."

Miss Beatty stiffened a moment, as if unaccustomed to being embraced. Certainly I'd never had the nerve to do so before.

"Now, now—no tears." She gave me a quick hug, then stepped back as if she'd done something wrong. Affection of any sort was not encouraged at Miss Medleycoate's Home for Orphan Girls. "Remember your manners, Florence. Always say please and thank you, and don't slurp your soup."

"Is that girl coming with us or not?" the coachman asked.

"Go along then, Florence." Miss Beatty gave me a gentle push toward the coach. As a passenger held out his hand to assist me, she said softly, "I pray you'll be happy in your new home."

Once inside the coach, I looked out the window just in time to glimpse Miss Beatty's broad back vanish into the crowd in the coach yard. The last I saw of her was the big yellow flower on her hat. She was the only grownup at Miss Medleycoate's Home for Orphan Girls who'd treated me—or any of us—with kindness.

On his rooftop seat, the coachman cracked his whip, and away we went, bouncing over cobbled streets and rattling through parts of London I'd never seen. I glimpsed the Tower, the dome of St. Paul's Cathedral, and mazes of twisting alleyways. Then we hurtled across Tower Bridge and into the narrow streets of Southwark, crowded with coaches, wagons, and people, all doing their best to move onward at the expense of everyone else.

In the crowded coach, I was squashed between a large redheaded woman and an even larger gentleman with a beard that threatened to scratch my cheek if I was jostled too close to him.

Directly opposite me sat a narrow-faced young man with a mustache and a wispy beard, attempting to read his Bible. Next to him a rough-looking fellow frowned and scowled at all of us. Making herself as small as possible, a timid lady with gray hair and spectacles pressed herself against the side of the coach.

Before five minutes had passed, the gentleman beside me fell asleep and commenced to snore loudly. On my other side, the stout woman fussed to herself and even went so far as to reach across me and poke the sleeper with her umbrella. She failed to rouse him.

Across from me, the rough fellow began a conversation with the Bible reader, which soon turned into an argument about Mr. Darwin's theory of evolution—the Bible reader for and the rough fellow against. The old lady closed her eyes and either fell asleep or feigned to.

The woman beside me opined that she was not descended from apes, no matter what Mr. Darwin had thought. She did not, however, voice her opinion loudly enough to be heard by the Bible reader and the rough fellow.

While all this went on about me, I mused upon the sudden change in my circumstances. My parents had drowned in a boating accident when I was five years old. When no relative stepped forward to claim me, I was sent to Miss Medleycoate's, where I spent seven wretched years learning to sew and read and write from a series of strict teachers who had little patience with girls who could not stitch a neat row or learn their arithmetic. We were cold in the winter, hot in the summer, and hungry all year round. If we dared to complain, we were beaten and locked in the punishment closet.

Then one day, just a week ago, a solicitor appeared at the orphanage and informed Miss Medleycoate that I was the great-niece of Thomas Crutchfield, my father's uncle. My uncle had searched for me a long time and had finally learned my whereabouts. As soon as proper arrangements were made, Mr. Graybeale said, I was to live at Crutchfield Hall with my uncle, his spinster sister, Eugenie, and my cousin James, the orphaned son of my father's only brother.

Glancing around the dreary sitting room, Mr. Graybeale had told me I was a fortunate girl.

"She certainly is." Miss Medleycoate fixed me with a sharp eye. "I am certain Florence will show her gratitude as she has been taught."

I knew full well how fortunate I was to escape Miss Medleycoate's establishment, but I merely bowed my head to avoid her stare. Now was not the time to express my feelings.

"What sort of boy is my cousin James?" I asked Mr. Graybeale. "Is he my age? Is he—"

"I've never met the child," Mr. Graybeale said, "but I hear he's rather delicate."

I stared at the solicitor, wondering what he meant. "Is he sickly?"

"Florence," Miss Medleycoate interrupted. "Do not pester the gentleman with trivial questions. Your curiosity does not become you."

"It's all right," Mr. Graybeale told Miss Medleycoate. Turning to me, he said, "The boy has suffered much in his short life. His mother died soon after he was born, and his father succumbed to a fever a few years later. Not long after James and his older sister, Sophia, arrived at Crutchfield Hall, the girl was

killed in a tragic accident. So much loss has been difficult for James to bear."

I stared at Mr. Graybeale. "I'm so sorry," I whispered. Perhaps I should not have asked about James's health, but if I had not, how would I have known about my cousin's tragic past and Sophia's death? Disturbing as these events were, I needed to be aware of them, if only to avoid asking my aunt and uncle inappropriate questions.

With a rustle of silk, Miss Medleycoate rose to her feet. "I believe Mr. Graybeale has satisfied your unseemly curiosity, Florence. You may return to your lessons while I sign the necessary papers."

Now, as the coach bounced and swayed over rough roads, I thought about Sophia. If only she hadn't died, if only she were waiting for me at Crutchfield Hall, the friend I'd always wanted, the sister I'd never had.

I imagined us whispering and giggling together, sharing books and games and dolls, telling each other secrets. We'd sleep in the same room and talk to each other in the dark. We'd go for long walks in the country. She'd show me her favorite things—a creek that swirled over white pebbles, lily pads in a pond, a bird's nest, butterflies, a tree with branches low enough to sit on and read. Maybe we'd have a dog or a pony.

Suddenly the coach hit a bump with enough force to hurl me against the man beside me. He drew away and scowled, as if offended by my proximity. Brought back to the stuffy confines of reality, I let go of my daydream. Sophia would not be waiting for me at Crutchfield Hall. I would have no sister. Just James, delicate James, a brother who might not be well enough to play.

With a sigh, I reminded myself that I was a fortunate girl. With every turn of the coach's wheels, I was leaving Miss Medleycoate's Home for Orphan Girls farther and farther behind. Surely I'd be happier at Crutchfield Hall than I'd been with Miss Medleycoate.

Two

AS THE CITY SLOWLY FADED away behind us, I caught fleeting glimpses of open countryside, green meadows rolling away toward distant hills, red-roofed villages marked by church steeples, cows and sheep under a cloudy sky much higher and wider than it looked in London. I felt very small, rather like an ant riding in a coach the size of a walnut shell.

After an hour or so, the sky darkened and the wind rose. Rain pelted the coach and streamed down the windows, making it impossible to see out.

We stopped several times to let passengers off and take more on. The rough fellow was replaced by a farmer who had nothing to say to anyone. The old lady was replaced by a young woman who blushed whenever anyone looked at her.

The coach grew stuffy, and the voices around me blended into a sort of soothing music. The jolts and bumps and lurches changed to a rocking motion, and I soon fell asleep.

I was startled awake by the large woman beside me. "Stir yourself, child. This is where you get off."

"Crutchfield Hall," the coachman bellowed from his seat above us. "Ain't there someone what wants to get out here?"

I scrambled to my feet and stepped outside. Wind and rain struck me with a force that almost knocked me down. Groggy with sleep, I gazed at empty fields bordered by a forest, bare and bleak on this dark January afternoon. In the distance, I saw a line of hills, their tops hidden by rain, but no house. Not even a barn or a shed.

Bewildered, I peered up at the coachman through the rain. "Where is the house, sir?"

Gesturing with his whip, he pointed to an ornate iron gate topped with fancy curlicues. "Follow the drive till you come to the house," he said. "It's one or two mile, I reckon. A big old place with chimneys. Pity there's no one to meet you."

With that, he handed me the small wooden box that held all my belongings. "Be sure and latch the gate behind you," he said. "They won't like it left open."

Before I could say another word, he cracked his whip. In seconds, the coach vanished into the rain.

With a sigh, I lowered my head and pushed open the heavy gate, then latched it behind me. The rain came down harder. The wind sent volleys of leaves flying against my face, as sharp edged as small knives.

Frightened by the creaking and groaning of tree limbs over my head, I walked faster, almost losing my shoes in the mud. They were thin soled, meant for city streets, not country lanes. I supposed I was meant for city streets as well, for I did not like the vast sky above me. The endless fields and the distant hills made me feel as if I were the only living person in this desolate place.

I was tempted to turn around and walk back to the road. Perhaps another coach would come along, warm and crowded with passengers, and take me back to London's familiar streets.

But I kept going, fearing Miss Medleycoate would not accept me. Had she not been happy to see me leave? I did not want to end my days begging in the street.

Finally, ankle deep in mud and soaked by the rain, I came to the top of a hill. Below me was a gloomy stone house, grim and unwelcoming, its windows dark and lifeless. Except for a dense grove of fir trees, the gardens and lawn were brown and bare.

A writer like Miss Emily Brontë would have been entranced by its Gothic appearance, but I hung back again, suddenly apprehensive of what might await me behind those towering walls.

It was the rising wind and icy rain that drove me forward. Exhausted and cold, I made my way carefully downhill to the house. In the shelter of a stone arch, I lifted an iron ring and let it thud against the door. Shivering in my wet coat and sodden shoes, I waited for someone to come.

Just as I was about to knock again, I heard footsteps approaching. The door slowly opened. A tall, thin woman dressed in black looked down at me. Her face was pale and narrow, her eyes were set deep under her brows, and her gray hair was pulled tightly into a bun at the back of her head. With a gasp, she pressed one bony hand to her heart. "It cannot be," she whispered. "It cannot be."

Fearing she was about to faint, I took her cold hand. "I-I'm Florence Crutchfield," I stammered. "From London. I believe you're expecting me."

She snatched her hand away and looked at me more closely. "For a moment I mistook you for someone else," she murmured, her voice still weak. "But now I see you bear no resemblance to her. None at all."

Without inviting me in, the woman said, "We were told you'd arrive tomorrow."

"I beg your pardon, but Miss Medleycoate said I was to come today." Panic made my heart beat faster. "She said I was to come today," I repeated. "Today."

At that moment, an old gentleman appeared in the shadowy hallway. The very opposite of the woman, he was short and round, and his cheeks were rosy with good humor. In one hand he held a pipe and in the other a thick book. "Come in," he said to me, "come in. You're wet and cold."

To the woman he said, "This poor child must be our great-niece Florence. Why have you allowed her to stand on the doorstep, shivering like a half-drowned kitten?"

"You know my feelings about her coming here." Without another word, she turned stiffly and vanished into the house's gloomy interior.

Puzzled by my aunt's unfriendly manner, I followed my uncle down the hall. What had I done to cause Aunt to dislike me almost on sight?

"As you must have guessed," my uncle said, "I'm your Great-Uncle Thomas, and that was my sister, your Great-Aunt Eugenie. I apologize for her brusqueness. I'm sure she didn't mean to be rude. She, er, she..."

Uncle paused as if searching for the right words to describe his sister. "Well," he went on, "once she becomes accustomed to you, she'll be friendlier. Yes, yes, you'll see. She just has to get used to you."

I didn't dare ask how long it would take Aunt to get used to me. Or how long it would take me to get used to her. Indeed, I felt I had escaped Miss Medleycoate only to encounter her double. Which was neither what I'd hoped for nor what I'd expected.

"And then of course," Uncle went on, "we really did expect you to arrive tomorrow. I'd have sent Spratt to meet you if I'd known you'd arrive today. A misunderstanding on someone's part, but, well, what's done is done. I am very happy to see you."

Uncle led me into a large room lit by flickering firelight and oil lamps. Rain beat against its small wind

ows, and the wind crept through every crack around the glass panes, but I felt cheered by the fire's glow and my uncle's smile.

"Here, let me have a look at you." Uncle grasped my shoulders and peered into my face. "Goodness, Eugenie, have you noticed how much she favors the Crutchfields? Blue eyes, dark hair—she could be Sophia's sister."

My aunt frowned at me from a chair by the hearth. "Don't be absurd. This girl is quite plain. And her hair is a sight."

Busying myself with my coat buttons, I pretended not to have heard Aunt. I didn't know what Sophia looked like, but I was quite ready to believe she was much prettier than I. Aunt was right. I was plain. And my hair was tangled by the wind and wet with rain and no doubt a sight.

Uncle took my sodden coat and settled me near the fire. "You must be tired and cold," he said. "You've had a long, muddy walk from the road." He picked up a bell and rang it.

A girl not much older than I popped into the room as if she'd been waiting by the door. She was so thin, she'd wrapped her apron strings twice around her waist, but the apron still flapped around her like a windless sail.

"Nellie," my uncle said, "this is Florence, the niece we expected to arrive tomorrow. Please bring tea for us all and something especially nice for Florence. Then build up the fire in her room."

Darting a quick look in my direction, Nellie nodded. "Yes, sir, I will, sir."

As she scurried away, Uncle turned back to me. "First of all, permit me to say how sorry I was to learn of your father's and mother's death. To think they died on the same day. So tragic. So unexpected."

"Sensible people do not go out in boats," Aunt said, and then, with a quick glance at me, added, "Death is usually unexpected. That is why we must endeavor to live righteously. When we are summoned, we will be ready. As Sophia was, poor child."

Ignoring his sister, Uncle patted my hand. "We'll do our best to make up for the years you spent with Miss Medleycoate. You'll have a happy life here at Crutchfield Hall, I promise you."

I did not say it, but the prospect of a happy life with Aunt seemed uncertain at best.

Mister Death's Blue-Eyed Girls

Mister Death's Blue-Eyed Girls The Ghost of Crutchfield Hall

The Ghost of Crutchfield Hall Hear the Wind Blow

Hear the Wind Blow Time of the Witch

Time of the Witch The Girl in the Locked Room: A Ghost Story

The Girl in the Locked Room: A Ghost Story All the Lovely Bad Ones

All the Lovely Bad Ones One for Sorrow

One for Sorrow Deep and Dark and Dangerous

Deep and Dark and Dangerous Tallahassee Higgins

Tallahassee Higgins Promises to the Dead

Promises to the Dead Took: A Ghost Story

Took: A Ghost Story Following My Own Footsteps

Following My Own Footsteps Wait Till Helen Comes: A Ghost Story

Wait Till Helen Comes: A Ghost Story Where I Belong

Where I Belong The Spanish Kidnapping Disaster

The Spanish Kidnapping Disaster Look for Me by Moonlight

Look for Me by Moonlight The Old Willis Place

The Old Willis Place Closed for the Season

Closed for the Season As Ever, Gordy

As Ever, Gordy Anna on the Farm

Anna on the Farm The Doll in the Garden

The Doll in the Garden Daphne's Book

Daphne's Book Witch Catcher

Witch Catcher The Gentleman Outlaw and Me--Eli

The Gentleman Outlaw and Me--Eli Wait Till Helen Comes

Wait Till Helen Comes Took

Took A Haunting Collection

A Haunting Collection Anna All Year Round

Anna All Year Round The Girl in the Locked Room

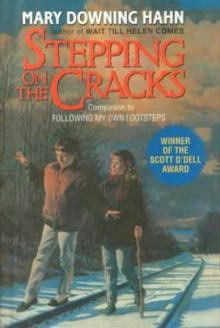

The Girl in the Locked Room Stepping on the Cracks

Stepping on the Cracks