- Home

- Mary Downing Hahn

The Spanish Kidnapping Disaster

The Spanish Kidnapping Disaster Read online

The Spanish Kidnapping Disaster

Mary Downing Hahn

* * *

CLARION BOOKS • NEW YORK

* * *

Clarion Books

a Houghton Mifflin Company imprint

215 Park Avenue South, New York, NY 10003

Text copyright © 1991 by Mary Downing Hahn

All rights reserved.

For information about permission to reproduce

selections from this book, write to Permissions,

Houghton Mifflin Company,

215 Park Avenue South, New York, NY 10003.

Printed in the U.S.A.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Hahn, Mary Downing.

The Spanish kidnapping disaster / by Mary Downing Hahn,

p. cm.

Summary: Forced to accompany their parents on their honeymoon in

Spain, new stepsisters Amy and Felix find the animosity between them

escalating especially when Felix's boasting about family wealth to a

stranger results in the kidnapping of the girls and their little

brother.

ISBN 0-395-55696-1

[1. Stepfamilies—Fiction. 2. Kidnapping—Fiction. 3. Spain—

Fiction.) I. Title.

PZ7.H1256Sp 1991

90-2439

[Fic]—dc20

CIP

AC

QUM 10 9 8 7

* * *

For my friends at the

International School of Stuttgart

and

The American School of Madrid

Without your help and companionship

this book could not have been written!

1

Although we didn't know it then, our troubles began when Amy lost her barrette. It was one of a pair decorated with cloisonné butterflies, and, if we'd been able to see into the future, neither one of us would have turned back to look for it.

We were in Toledo, Spain, at the time, but, because of the situation, we weren't having much fun. You see, my mother had just married Amy's father, a union we had both opposed, and now, due to circumstances beyond everybody's control, Amy, her little brother, Phillip, and I were tagging along on the honeymoon. No one, including Mom and Don, was enjoying our first experience as a family.

Don't ask me why I agreed to help Amy search the gutters of Toledo for something less than two inches long. I certainly didn't care whether her hair fell in her eyes or not. Combed or uncombed, washed or unwashed, it always looked better than mine. What's more, I didn't like Amy, and she didn't like me. I think I went with her because I was tired of walking behind Mom, ignored and forgotten while she held hands with Don. I was definitely fed up with Phillip, one of the most irritating ten-year-olds I'd ever met.

Anyway, it was late afternoon, and Amy and I had been dragging along behind the others, too hot and tired to walk faster or even quarrel. Several feet ahead, Phillip was practicing his Spanish on every innocent bystander he saw. Mom was reading loudly from her guidebook, unaware that nobody was listening. And Don was photographing alleys, stairways, people, cats, dogs, pigeons—ordinary things tourists never noticed but which he felt represented the real Spain. No one was paying any attention to Amy or me. I suppose our parents thought two twelve-year-old girls could take care of themselves.

Then Amy noticed her barrette was gone, and, while Phillip, Mom, and Don strolled on, we walked off in the opposite direction to look for it. While Amy peered into every crack and crevice big enough to hide the barrette, I paused to take a picture of some brightly colored laundry hanging on a sunny balcony. Suddenly, a crowd of tourists in black business suits filled the street and began photographing the laundry too. There were so many of them Amy and I couldn't see past them or even wiggle around them. By the time they'd put their cameras away and moved on to the next attraction, we didn't see Mom, Don, or Phillip anywhere.

The barrette forgotten, we looked at each other. "Where did they go?" Amy asked.

Hoping to catch up with our parents, we ran to the corner, but all we saw were the backs of the tourists disappearing around a turn in the street.

"Mom said something about the Alcázar," I said. "We'll just ask somebody how to get there. It's such a big old building, I bet everyone knows where it is."

"But we're in Spain," Amy reminded me. "Suppose we can't find anyone who speaks English?"

"No problem," I said with more confidence than I felt. "I have a great sense of direction."

From the way Amy looked at me, I knew she had no faith in me or my sense of direction. Probably she was remembering the time I'd shown her a shortcut to the mall, and we'd ended up lost in a swamp. She'd ruined her favorite sandals, fallen into a patch of poison ivy, and been bitten by three million mosquitos before we found our way to dry ground. Amy's not the kind of person who forgets a thing like that, especially if she thinks you did it on purpose.

"Tell the truth for once," she said crossly. "You don't have the slightest idea where the Alcázar is and you know it."

"Don't get mad and blame this on me," I said. "You're the one who lost the barrette. I was just trying to help you find it."

Making an attempt to stay calm, I looked at the silent buildings and the empty streets, but they offered no clues to the Alcázar's whereabouts. It could have been uphill or down, east, west, north, or south. And there was no one to ask. A white cat regarded me solemnly from a balcony. A dog wandered past, sniffing the curb. A flock of pigeons flew up into the air with a clatter of wings. But not a single person appeared. All the doors were closed, and the windows were shuttered against the hot June sun.

"What should we do?" Amy asked, suddenly tearful.

Not wanting to admit I was just as scared as she was, I took a wild guess and pointed down the street. "It's that way."

"Are you sure?" Amy asked suspiciously.

Without answering, I walked off as if I knew exactly where I was going, and Amy followed me. After trudging along in silence for about five minutes, we turned a corner and saw a sunlit square. A number of streets curved out of it, but there was no sign of the Alcázar.

"Now what, Miss Know It All?" Amy glared at me. Without the barrette, her hair tumbled down over one eye, and she brushed it back from her face impatiently. Half moons darkened the armpits of her blue tee-shirt, and she looked as hot and cross as I felt.

Across the square, a woman sat on the curb adjusting her sandal strap. A shabby backpack leaned against the wall behind her. Although she was wearing faded jeans and a tee-shirt, the flower in her long red hair gave her a foreign look.

"Maybe she can help us," I said.

"I bet she won't understand a thing you say," Amy muttered, but she crossed the square with me.

I stopped in front of the woman. When she didn't look up, I cleared my throat nervously. "Excuse me," I said, "do you speak English?"

The woman smiled. "I have a little English," she said, forming each word slowly and carefully. "You are lost?"

Fascinated by her accent, I stared at her, momentarily speechless. She wore big gold hoops in her ears, and she was beautiful in a way Amy, pretty as she was, would never be. Tall and slender, the woman reminded me of a model I'd seen once on the cover of Vogue. She had the same high cheekbones, big eyes, and square chin. Except for a sprinkle of freckles bridging her nose, her skin had been bronzed by the sun to a smooth rosy gold.

"We got separated from our parents," Amy said, "and now we can't find them." She frowned as if she didn't expect much help from a person who couldn't speak perfect English, and her eyes brimmed with tears.

"They were on their way to the Alcázar." My v

oice came back in a rush as I tried to make up for Amy's unfriendliness. "Can you tell us how to get there?"

The woman rose and hoisted her backback onto her shoulders. It was very heavy from the look of it. "I go toward the Alcázar myself. I will take you," she said. "Girls of your age should not be alone in the streets. There is danger. Many thieves, pickpockets. You must be careful with whom you speak."

Amy looked at me as if her every fear had just been vocalized. Then she scrutinized the woman's face and clothes as if she weren't sure she should speak to her, let alone accompany her through the streets of Toledo.

"Don't just stand there," I said to Amy as the woman began to walk away. "You heard what she said. She'll take us to the Alcázar."

Amy sighed and shoved her hair behind her ears. "I hope so," she muttered, but, to my satisfaction, she followed me down the narrow street our guide had taken.

What choice did either one of us have? There was no one else to ask, no one else to follow.

2

Leaving Amy behind, I caught up with the woman. "My name is Felix," I said. "What's yours?"

"Felix?" She stared at me. "Never have I met a girl called Felix. That is most unusual, even in America, is it not?"

"My real name is Felicia," I admitted, "but nobody calls me that except my mother when she's mad at me."

"Well, then, Felix, I am glad to meet you." The woman offered me her hand and I shook it.

"I am Grace," she went on, "and I am a traveler here in España. That is not the same as a turista, you know. Unlike most strangers in this beautiful country, I am in love with Spain. The sun, the golden light it gives, the old stone that glows. It is in my soul, mi alma." Grace struck her chest forcibly with her fist. "You understand?"

"Oh, yes," I said. "I adore Spain too." To prove it, I thumped my chest so hard it hurt.

Grace smiled at me and then looked at Amy. If she expected a similar display of passion from her, she was disappointed. Amy was paying no attention to Grace and me. From the way she was staring at buildings and street names, you would think we were still lost.

"Are you sisters?" Grace asked me.

"No!" I said quickly. "My mother just married her father. This is their honeymoon."

"They have brought you with them?" Grace sounded surprised.

"Well, they didn't mean to. We were supposed to stay with Amy's grandmother, but she fell and broke her hip just before the wedding, so here we are."

"You must be very rich to take such a trip together," Grace said.

"Not really," I said, trying to be modest and truthful, two qualities which did not come easily to me.

"Oh, please, I know better. All Americans are rich," Grace said. "They say they are not, but in your country the poorest one is richer than most in my country. I think you all live like the television shows I see. Dallas, Dynasty, Falcon Crest. You are fortunate, Felix, very, very fortunate."

Grace's eyes narrowed a little, and, for a second, I was afraid she had taken a sudden dislike to me. Then she smiled, and I felt better again. She'd sized me up, I thought, and decided I was okay after all.

"Tell me about yourself," she said. "Where do you live? What is your home like? Is it big like the ones on television?"

"We just bought a new house," I began truthfully enough, "in Woodhaven Estates. It's got a big yard, and five bedrooms. Very expensive. You should see my room. The walls are pale lavender, and I have a canopy bed with lots of pillows and wall-to-wall carpeting. I have my own TV too, one of those big screens built into the wall so it's almost like being at the movies."

When I paused for breath, I noticed Amy was staring at me. She was probably jealous because Grace was paying attention to me instead of her. Amy's used to being the star attraction.

Or was it because I was beginning to exaggerate? It wasn't quite true what I'd said about my room. I did have a canopy bed, bought cheap at a yard sale, but my TV was an old black and white portable that only picked up three channels. And there was so much junk on the floor most of the time you couldn't even see the carpet.

Ignoring Amy, I smiled at Grace and moved into a higher gear of exaggeration, one that came pretty close to lying. "My real father," I said, "gives me everything I want. When I go home, he's going to buy me a horse."

"Ah," said Grace. "Your own horse, Felix, how lovely."

"Yes, a purebred Arabian, I think." I didn't dare look at Amy for fear she would tell Grace there was no way my father would ever buy me a horse. He had about as much interest in me as you might have in a pair of shoes you'd outgrown. Mom was lucky to get a child support check from him once or twice a year, especially since he'd remarried and started a new family. I once heard her tell someone I was his practice kid. But why tell Grace the truth?

Basking in her attention, I chattered on and on about Mom's Volvo and Don's Porsche. To keep the conversation going, I threw in descriptions of the Jacuzzi and the swimming pool we'd be getting soon, the country club we'd be joining, and the private school I might attend in the fall. I actually told Grace my mother had a mink coat even though she belongs to Greenpeace and hates women who wear fur.

And what was Amy doing while I let my tongue run away with my brain? She was stalking along behind us, her mouth shut as tight as the lid on a new peanut butter jar. I knew she was mad, but I couldn't stop talking. The more Grace believed, the more I lied.

Later, of course, I realized I'd made a big mistake. But it was partly Amy's fault. Instead of sighing and shaking her head, she should have told Grace the Volvo was twelve years old and in need of major repairs, she should have told her the Porsche burned oil and spent most of its time in the shop. She should also have said there were no Jacuzzis, private schools, fur coats, country clubs, or horses in our future.

But did she? No indeed. Amy let me blab on and on, and she didn't even try to stop me. Not once.

3

After a long, hot walk up and down hills and in and out of little squares, we came to the cathedral. Wiping the sweat from her forehead, Grace leaned against a wall and shrugged her backpack from her shoulders.

"Ah," she sighed, "that's better. It gets so hot and heavy sometimes."

Just as I was making myself comfortable in a shady place, Amy turned to Grace. "Are you sure you know where the Alcázar is? It seems to me we should've gotten there a long time ago."

"Do not worry, it is not far now," Grace said. "I must rest for a while. Be patient, please." Ignoring Amy's restlessness, Grace bent down to examine the strap of her sandal again. The leather was frayed, and she was having trouble keeping it buckled.

In the sunny square, a few feet away, a man stood in front of an easel. He was painting a picture of the cathedral. Ignoring Grace and me, Amy watched him silently. Her face was as expressionless as the stone angels peering down at us from the walls, but I knew she was angry. Sooner or later, I was going to hear about this episode. Like our adventure in the swamp, Amy would add being lost in Toledo to her list of grievances.

Well, it was too late to worry about Amy. Besides I wanted to learn more about Grace. "Now that I've told you all about me," I said, "what about you?"

Grace shrugged. "Me? There is nothing to tell, Felix."

"Oh, there must be." I gazed at her, soaking up the aura of mystery that surrounded her. "For instance," I persisted, "where are you from?"

"It is not important," Grace said. "I am a wanderer, a nomad. I left my home behind many years ago."

"Are you Spanish?"

"No." Grace smiled as if she were playing Twenty Questions with me.

"Well, what then?" I asked, annoyed to be treated like an ignorant child. "Are you French? German? Russian?"

Grace tossed her hair, and her earrings swayed against her cheeks. "Call me a citizen of the world, if you must, someone from everywhere and nowhere."

I paused a moment to catch my breath and think about that—a citizen of the world. It sounded so exotic, so free, so sophisticated. Gazing up at the cathedral's

spires, I decided I too would be a person from everywhere and nowhere. As soon as I graduated from high school, I would cram my belongings into a backpack, fasten a flower in my hair, and leave home forever.

"You must live somewhere." Amy's dry, practical voice interrupted my fantasy of myself as a woman with haunted eyes, leaving a string of broken-hearted men behind me as I roamed the beaches of Portugal or climbed the mountains of Tibet, always alone, shadowed by past tragedies.

"I made homes in many places," Grace told Amy. "Egypt, Israel, Turkey, here in España."

Amy was obviously not impressed by Grace's answer. Looking at her watch, she frowned. "Fascinating as this is, I wish you'd either take us to the Alcázar or tell us how to get there. My father must be worried to death about me."

From the way Amy spoke you would think Don and Don alone cared where we were. My mother was probably worried too—that is, if she'd noticed my absence. The way she acted around Don, holding his hand, kissing him, clinging to him, she might have forgotten she had a daughter by now.

"Forgive me," Grace said to Amy. "I would not want to worry your father." Hoisting her backpack into place, she set off across the square.

"You are so rude," I whispered to Amy. "Can't you see how tired she is?"

"At least I'm not dumb enough to be taken in by all that citizen of the world stuff," Amy said. "She's probably a bigger liar than you. If that's possible."

Hoping Grace hadn't heard Amy, I hurried after her. She was halfway up a narrow flight of stairs, a shortcut to the street above. The houses on either side were so close you could stretch out your arms and touch them, and the steps were worn down in the middle by the feet of all the thousands of people who had climbed them. Like everything in Toledo, they were old and romantic and mysterious.

At the top, Grace paused to readjust her backpack. We had reached a narrow street, partly shaded by tall buildings. The sunlight slanted down a wall, glinting on Grace's hair and etching tiny lines around her eyes.

"Where do you go next, Felix?" she asked. "After you leave Toledo?"

Mister Death's Blue-Eyed Girls

Mister Death's Blue-Eyed Girls The Ghost of Crutchfield Hall

The Ghost of Crutchfield Hall Hear the Wind Blow

Hear the Wind Blow Time of the Witch

Time of the Witch The Girl in the Locked Room: A Ghost Story

The Girl in the Locked Room: A Ghost Story All the Lovely Bad Ones

All the Lovely Bad Ones One for Sorrow

One for Sorrow Deep and Dark and Dangerous

Deep and Dark and Dangerous Tallahassee Higgins

Tallahassee Higgins Promises to the Dead

Promises to the Dead Took: A Ghost Story

Took: A Ghost Story Following My Own Footsteps

Following My Own Footsteps Wait Till Helen Comes: A Ghost Story

Wait Till Helen Comes: A Ghost Story Where I Belong

Where I Belong The Spanish Kidnapping Disaster

The Spanish Kidnapping Disaster Look for Me by Moonlight

Look for Me by Moonlight The Old Willis Place

The Old Willis Place Closed for the Season

Closed for the Season As Ever, Gordy

As Ever, Gordy Anna on the Farm

Anna on the Farm The Doll in the Garden

The Doll in the Garden Daphne's Book

Daphne's Book Witch Catcher

Witch Catcher The Gentleman Outlaw and Me--Eli

The Gentleman Outlaw and Me--Eli Wait Till Helen Comes

Wait Till Helen Comes Took

Took A Haunting Collection

A Haunting Collection Anna All Year Round

Anna All Year Round The Girl in the Locked Room

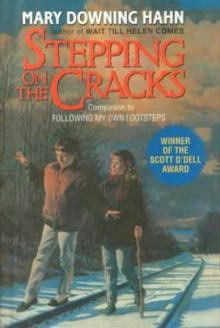

The Girl in the Locked Room Stepping on the Cracks

Stepping on the Cracks