- Home

- Mary Downing Hahn

Mister Death's Blue-Eyed Girls

Mister Death's Blue-Eyed Girls Read online

Table of Contents

Title Page

Table of Contents

Copyright

Dedication

Prologue

Part One

Party in the Park

Drinking Beer and Making Out

Part Two

The Last Day of School

At Ellie's House

Accused

Running Home

Later the Same Day

Nora's Dream

Part Three

The Long Way to Ellie's House

The Detectives

Night Thoughts

Part Four

Just Suppose

The Viewing

The Last Visit

Part Five

Bobbi Jo's Funeral

Ball on a Chain

Bobbi Jo's Funeral Procession

Bobbi Jo's Burial

Sacred to the Memory

Cheryl's Funeral

Cheryl, Cheryl, Cheryl

At the Reservoir with Charlie

In Trouble

Part Six

Repercussions and Departures

Cheryl's Diary

Bobbi Jo's Diary

A Visit to the Priest

A Talk with Nora

A Meeting at the Gas Station

Cheryl's Diary

Bobbi Jo's Diary

Lonely Street

Part Seven

Dr. Horowitz

Ocean City

Ellie's Diary

Ready to Leave Town Except for One Thing

Another Secret Meeting Nora

Nora, Nora—What the Hell

Secrets

Cheryl's Diary

Ellie's Letter

Part Eight

The Bookstore Beatnik

Five Pines Swimming Pool

Part Nine

What Is the Grass?

A Talk with Ralph

Buddy's Letter

Ellie Comes Home

Nora's Second Dream

Part Ten

Memories

Afterword

CLARION BOOKS

215 Park Avenue South, New York, New York 10003

Copyright © 2012 by Mary Downing Hahn

"Buffalo Bill's" copyright 1923, 1951, © 1991 by the Trustees for the E. E. Cummings Trust. Copyright © 1976

by George James Firmage, from Complete Poems: 1904–1962 by E. E. Cummings, edited by George J. Firmage.

Used by permission of Liveright Publishing Corporation.

All rights reserved. For information about permission to reproduce selections from this book,

write to Permissions, Houghton Mifflin Harcourt Publishing Company,

215 Park Avenue South, New York, New York 10003.

Clarion Books is an imprint of Houghton Mifflin Harcourt Publishing Company.

www.hmhbooks.com

The text was set in ITC Legacy.

Book design by Sharismar Rodriguez

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Hahn, Mary Downing.

Mister Death's blue-eyed girls / by Mary Downing Hahn.

p. cm.

Summary: Narrated from several different perspectives, tells the story of

the 1955 murder of two teenaged girls in suburban Baltimore, Maryland.

ISBN 978-0-547-76062-9

[1. Coming of age—Fiction. 2. Murder—Fiction. 3. Grief—Fiction.

4. Baltimore (Md.)—History—20th century—Fiction.] I. Title.

PZ7.H1256Mr. 2012

[Fic]—dc23

2011025950

Manufactured in the United States of America

DOC 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

4500343699

To Jim

who has encouraged me to write this story since 1980

Prologue

Friday, June 15, 1956 Before Dawn

HE opens his eyes. It's still dark, way before dawn. He'd willed himself to wake at three a.m., and he's done it. He hadn't dared to set the alarm. What if someone heard it go off? No, he and his brother must leave the house without anyone knowing. Not his family. Not the neighbors.

Without turning on the light, he dresses slowly, carefully—dark shirt, dark pants—then glances at his dim reflection in the mirror. His face looks the same as usual. A pale oval in the shadows, expressionless. The kind of face nobody remembers.

He smiles at himself. The man you meet at the top of the stairs, that's who he is: the man who isn't there. The man you should pay attention to, the man you shouldn't offend. Vengeance is mine, sayeth the man who isn't there.

Quietly he opens his kid brother's door. He's still asleep, head under the covers even though it's June and already hot.

He touches his shoulder lightly and whispers, "It's time."

His brother sits up quickly, startled. Has he forgotten what they're going to do today?

"Get dressed," he says in a low voice.

His brother hunches his shoulders and looks up at him—a kid. Still a kid. Always the baby.

"You can't back out," he whispers. "We're brothers. A team."

"I been thinking," his brother says. "I'm not so sure..."

His brother is scared. He can almost smell it on his breath and in his sweat. He squeezes his brother's arm until he winces and tries to pull away. He tightens his grip, hurting him, not caring. "Get up," he mutters. "You gave me your word."

"Yeah, but maybe—"

"Maybe nothing."

His brother looks like he might cry. "They didn't do anything to me," he whines.

"What somebody does to me, they do to you. That's what being brothers means." He gives him a yank. "Get dressed."

His brother gets out of bed. He pulls on jeans and a dark T-shirt. Now they look like twins. Neither one worth looking at twice.

Slowly they go downstairs. They hear their father snoring. Their mother mumbles in her sleep. Ordinary, everyday stuff. Nothing unusual. Yet.

In the basement rec room, he goes straight to the stag's head mounted over the TV, a trophy from his father's hunting days. Gently he lifts the rifle from its resting place on the stag's hooves. Nice touch, that—include the hooves so you can display the deer along with the gun that killed him.

He loaded the rifle last night. It's ready to go.

In the kitchen his brother is waiting, tense, still scared. Together they sneak outside into the darkness. The row houses are silent. Not a light anywhere. Not a car to be seen or heard. He and his brother could be the only people in the world, surviving on their own in some kind of science-fiction novel. Not such a bad idea.

They cross the road and lose themselves in the park's shadows. They pass swings hanging empty but twirling slowly in the breeze, chains clinking like tiny bells. They pass the sliding board, a sheet of silver in the darkness; the jungle gym, the rec center, a barbecue grill, picnic tables. To their left is the baseball diamond. And the lake. To their right is the woods.

They go to the right, slipping through the trees like Indians, their tennis shoes as silent as moccasins. They cross a small bridge over a creek. The water gurgles. A frog croaks. The water smells of mud and dead weeds.

They stop about ten feet from the bridge, at the foot of a maple tree with low limbs perfect for climbing. Holding the rifle carefully, he scrambles from branch to branch, up into the leaves.

"Can you see me?" he whispers to his brother.

"No." His brother peers up into the tree. "You want me to climb up there, too?"

"We talked about this yesterday. Hide in the bushes. When you hear the gun, come running. I'll need you to help me then."

His brother looks around uneasily. He's still scared. "I

t's so dark," he says. "Why can't I stay with you?"

He scowls down at him, frightening him even more with the fierceness of his face. "You'd better not ruin this."

Stinking with fear, his brother backs away toward the lake. "I won't mess up," he says in a shaky voice. "I'll help you like I promised."

He watches his brother disappear into the shadows. For a while he hears him crashing through the undergrowth. He sighs. His brother is a loser. Not as smart as he is, not as quick. Slow and clumsy and as nervous as a girl—that about sums it up.

At last the woods are silent again. Except for the birds. They're waking up and singing like they're auditioning for a Disney cartoon. So damn optimistic. So cheerful. So happy to be alive. They get on his nerves. He aims the rifle at a mockingbird on a nearby branch. Fingers the trigger. Doesn't pull it, though. Not because he doesn't want to.

He leans his head against the tree trunk and breathes in the smell of damp woods. It's like when he was little and his father took him hunting and they waited in a tree for a deer to step out of the bushes. Patience, it takes patience.

Part One

The Day Before

Party in the Park

Thursday, June 14

Nora

DESPITE the summer heat, I'm sprawled on my bed, radio turned up loud to get the full benefit of Little Richard singing "Tutti Frutti." Dad's not home from work and Mom's outside hanging up the wash, so there's nobody to scream "Turn that radio down!"

The window fan blows warm air on my face. I close my eyes and drift off into a daydream about Don Appleton, a boy in my art class. I've loved him since eighth grade. Not that he knows it. Not that he loves me. Anyway...

The car radio blasts "Tutti Frutti," and the wind blows through my hair. Don smiles at me as he slides one arm around my shoulder, and I move closer to him, till I'm practically sitting in his lap. The way Cheryl rides with Buddy, her hand on his thigh. He kisses me and someone blows a horn at us. "You're so pretty," he whispers. "I really like you."

Up ahead is the frozen custard stand. Peggy Turner—Don's real-life girlfriend—is there with her friends. They all stare. They can't believe Don is with me. Right in front of them, he kisses me again, and then he—

"Nora, phone!" my little brother hollers up the steps. "Phone!" Jolted out of my daydream, I holler back, "Who is it?" I'm too hot to move.

"I don't know," he yells. "Some girl."

Dull from the heat, I go downstairs and take the phone from Billy.

It's Ellie. "A bunch of kids are getting together in the park tonight," she says. "Can you come?"

My mood suddenly improves. "Sure," I say.

"Sleep over at my house," she says. "We'll walk to school together tomorrow. Last day! Yay!"

"Who's coming?" I cross my fingers and hope Ellie will say Don, Don will be there. Which is silly, because he isn't in the same crowd. Don's on the basketball team. He dates cheerleaders and majorettes. He lives in Dulaney Park, the rich part of town. I got Mom to drive me by his house last Halloween, just to see what it looked like. I was scared he might see me, so I crouched on the floor and peeked out the car window. His house was all lit up. Some trick-or-treaters were ringing the doorbell, and I told Mom to drive on in case Don came to the door.

"All the kids will be there," Ellie says. "Paul, Gary, Charlie, Cheryl, and lots more. You know how our neighborhood is."

"More exciting than mine, that's for sure." As I speak, I see Mr. and Mrs. Clements drift past our house, their little dog trailing behind them. They're old. Their dog is old. Old houses, old people—I guess they go together. Not a person on our block is under forty except Billy and me. Boring, boring, boring.

Ellie lives a mile away on the other side of Elmgrove, in Evergreen Acres. It used to be woods when I was little. Block after block, street after street of row houses built after the war for veterans and their families.

Everybody's young there, even parents. Most of the dads fought in Europe and Africa and all those islands in the Pacific. My dad was too old for the draft, but Ellie's father was in the navy. Joined up after Pearl Harbor, the first guy in his town, he told me.

And the kids there—dozens of them, from babies to teenagers. Bikes and wagons and sandboxes in every yard, hopscotch games drawn on the sidewalks, toys scattered on front steps, baby carriages and strollers on porches, ball games in the street, dances in the rec center, souped-up cars with loud radios. It's never boring on Ellie's street.

After dinner, I toss what I need into my overnight case, kiss Mom, make a face at Billy, and follow Dad to the old Buick parked in the driveway. He grumbles about driving me over there, but I'm thinking he doesn't really mind because he can have a beer with his buddies at the Starlight on the way home.

When we're near Ellie's house, I tell Dad, "Just let me out at the corner of Thirty-Third and Madison. Then you won't have to bother with turning around and all."

He glances at me and nods. I hope he hasn't guessed how much the old Buick embarrasses me. Not only is it out of style, but it has dents on the side and the paint is faded and dull. Inside, the drab ceiling liner sags and the upholstery is torn and frayed. The scratchy old army blanket covering the back seat is disgusting. In the heat, it smells like dust.

Worst of all, the radio's broken. If my parents ever think I'm responsible enough to get my driver's license, I can't possibly take my friends anywhere in a car that doesn't have a radio.

The thing is, Dad's an automobile mechanic. Not that you'd guess it. He's English, and he has a posh accent to prove it. Most people think he's a college professor at Towson State. Sometimes I let them go on thinking that.

Anyway, he keeps the Buick running like a top—to quote him. What does he care what the car looks like? What's important is the engine.

"Here?" Dad pulls over on the shoulder and stops.

I open the door, eager to escape before anyone sees me getting out of the car. "That's Ellie's house right there, three doors down." I point at the brick row houses, each with its own small yard and its own chain-link fence. Where I wished we lived instead of in a poky old bungalow down at the wrong end of Becker Street, two doors up from the train tracks.

Ellie's waiting at the door, ready to go. Like me, she's wearing short shorts, a sleeveless blouse, and scuffed white Keds. Her red hair is pulled back in a curly ponytail. "Dump your stuff in the hall," she says. "The rec center just opened."

Mrs. O'Brien sticks her head out of the kitchen and smiles. "Good to see you, Nora."

"You, too." I smile at Ellie's mother. She's dark-haired and sweet-faced, younger than Mom and fun to be around. Best of all, she makes me feel welcome. Special, even. Ellie's friend. Catholic like Ellie. Not the kind of girl you worry about. A nice girl.

In other words, a boring girl. A flat-chested, tall, skinny girl. Not the kind to sneak out or smoke or be a bad influence.

"Gary's bringing his records," Ellie tells me as we leave the house. "He's got everything—Fats Domino, Little Richard, Shirley and Lee, the Platters, Chuck Berry, Bill Haley, the Crew-Cuts, Bill Doggett."

We cut across the ball field to the rec center, a low cinderblock building backing up to the woods. In the daytime, it's a summer camp for little kids who sit at picnic tables and weave misshapen potholders on little metal frames, string beads on string, squish clay into lopsided bowls—the same old boring craft projects I hated when I was little. The kind of stuff adults think is creative.

At seven thirty, the sun is low enough to cast long shadows across the grass. The rec center's white walls reflect the sky's pink light. I hear the Penguins singing "Earth Angel." The song transforms the hot, dusty park into a place where a boy could fall in love with you—or break your heart.

"Oh, no. Look who's here." Ellie grabs my arm and points at the parking lot beside the rec center. Buddy's sitting on the hood of his old black Ford, smoking a cigarette. Hair smoothed back into a perfect ducktail, white T-shirt with the sleeves rolled up to hold a pack of Lu

ckies, Levi's low on the hips, motorcycle boots even though he doesn't have a motorcycle. A cool cat, that's how he sees himself. Short and skinny and weasel-faced, that's how Ellie and I see him.

"Why's he hanging around here?" I ask. "I thought all the graduates went to Ocean City the minute they got rid of their caps and gowns. It's what I'm doing next year." I picture myself lying on the beach, getting a good tan. A boy walks toward me—Don, of course, by himself for once. He sees me, he smiles, he—

Ellie says, "I hope he's not planning to start something with Cheryl."

"She broke up with him at least a month ago," I say. "I thought it was all over between them."

Ellie shakes her head. "For her, but not for him. He calls her all the time. She won't talk to him, she tells him to stop calling her, but he keeps on doing it. Her parents won't let him near the house, so he parks his car down the street and watches for her to come out. She won't go anywhere unless Bobbi Jo or I go with her."

"I didn't know that." I'm thinking how much in love they used to be, always together—CherylandBuddy, BuddyandCheryl. I'd seen their names carved on a tree in the park and scratched in cement on a new sidewalk. I'd thought then it was true love, it would last forever.

"There's lots you don't know, Nora." Ellie drops her voice to a whisper, her eyes widen. "Remember that black eye she had last April? Buddy did that."

I stare at Ellie, horrified. "She's never told me anything like that."

"She walks to school with me almost every day now. She tells me stuff then." Ellie pauses. "Actually, I wasn't supposed to tell anybody about the black eye. So don't mention it, okay?"

I glance at Buddy, still lounging by his car. "I hate him." And I really do. I feel my hatred, I taste it, dark and bitter.

"Me too." Ellie's voice rises. We stand there and glare at Buddy.

He turns his head, sees us, and waves. He doesn't know what we know. We look the other way and pretend not to notice him.

Behind us, we hear Cheryl calling, "Wait up!" She's with Bobbi Jo, Ellie's neighbor. They run to catch us, backlit by the setting sun, one a little taller than the other, both blond, Cheryl's hair in a long ponytail, Bobbi Jo's short and curly. They're both wearing white shorts and blue shirts. I can't help noticing that Cheryl's shorts are tighter and shorter than Bobbi Jo's. Her blouse is also cut much lower, lots lower than I'd dare wear. But then, I don't have as much on top as she has. They're both wearing too much bright red lipstick. Cheryl's idea, I think.

Mister Death's Blue-Eyed Girls

Mister Death's Blue-Eyed Girls The Ghost of Crutchfield Hall

The Ghost of Crutchfield Hall Hear the Wind Blow

Hear the Wind Blow Time of the Witch

Time of the Witch The Girl in the Locked Room: A Ghost Story

The Girl in the Locked Room: A Ghost Story All the Lovely Bad Ones

All the Lovely Bad Ones One for Sorrow

One for Sorrow Deep and Dark and Dangerous

Deep and Dark and Dangerous Tallahassee Higgins

Tallahassee Higgins Promises to the Dead

Promises to the Dead Took: A Ghost Story

Took: A Ghost Story Following My Own Footsteps

Following My Own Footsteps Wait Till Helen Comes: A Ghost Story

Wait Till Helen Comes: A Ghost Story Where I Belong

Where I Belong The Spanish Kidnapping Disaster

The Spanish Kidnapping Disaster Look for Me by Moonlight

Look for Me by Moonlight The Old Willis Place

The Old Willis Place Closed for the Season

Closed for the Season As Ever, Gordy

As Ever, Gordy Anna on the Farm

Anna on the Farm The Doll in the Garden

The Doll in the Garden Daphne's Book

Daphne's Book Witch Catcher

Witch Catcher The Gentleman Outlaw and Me--Eli

The Gentleman Outlaw and Me--Eli Wait Till Helen Comes

Wait Till Helen Comes Took

Took A Haunting Collection

A Haunting Collection Anna All Year Round

Anna All Year Round The Girl in the Locked Room

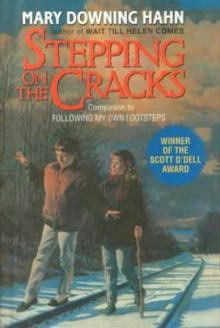

The Girl in the Locked Room Stepping on the Cracks

Stepping on the Cracks