- Home

- Mary Downing Hahn

A Haunting Collection Page 2

A Haunting Collection Read online

Page 2

“Don’t hold on so tight,” Dulcie interrupted. “Ali’s growing up. She has to start making her own decisions. It might be good for her to get away from you. She—”

“You always took everything away from me when I was little!” Mom shouted. “And now you want my own daughter! Can’t I have anything?” She started sobbing.

“Oh, that’s right,” Dulcie said. “Cry when you can’t think of anything else to do.” There was an edge of cruelty in her voice I’d never heard before. “Grow up, Claire. You’re not a little kid anymore.”

Emma put her arms around my neck and pressed her face against my chest. “Make them stop, Ali.”

The voices in the kitchen dropped so low that I couldn’t hear what Mom or Dulcie was saying.

“I think they stopped all by themselves, Emma.” I patted her back, but my mind was racing. Dulcie was right. Mom did overprotect me; even Staci thought so. She never let me do anything—not even spend a night at Staci’s house or go the mall with my friends. I really did need to get away from her for a while.

But at the same time I was agreeing with Dulcie, I was feeling bad because she’d upset Mom. I was confused, as well. Why did Mom think Dulcie wanted to take me away from her? What else had she taken? It was enough to give me a headache.

Emma nudged me. “Read, Ali. I want to hear the part where Little Bear and Edith play dress-up, and Edith writes, ‘Mr. Bear is just a silly old thing!’ on the mirror with lipstick and Mr. Bear gets cross.” She giggled. “And then Edith calls him a silly and he spanks her and she’s scared Mr. Bear will take Little Bear and go away and she’ll be lonely again.”

“You sure know this story well.”

“Edith is lonely like me, and she has blond hair like me, and she lives in an apartment in New York like me. And she wishes so hard for a friend that Mr. Bear and Little Bear come to her house just to be her friends. And that’s what I wish for, too. A friend. Somebody who likes me best of all.”

I started reading again, and Emma pressed against me, mouthing the words silently as if she knew the story by heart.

While I read, I kept one ear tuned to the kitchen, but I couldn’t hear what Mom and Dulcie were saying. If Emma hadn’t been sitting on my lap, I would have tiptoed to the door and listened.

3

At the end of the story, Mr. Bear promised Edith he’d stay with her forever.

“‘Forever and ever!’” Emma shouted along with Little Bear.

We said the book’s last three words together: “‘And they did!’”

“When I was little, I wanted a doll just like Edith,” I told Emma.

“I want one, too,” Emma said, “but Mommy says they’re very, very expensive.”

I sighed, thinking about things that cost too much to own—a horse, a mountain bike like Staci’s, a swimming pool in the backyard, even a doll. . . .

The front door opened, and Dad stopped at the threshold to grin at Emma, who ran to him.

“What a nice surprise!” Dropping his briefcase, he scooped Emma up and gave her a hug. “Look at you—just as beautiful as your mommy!”

Emma laughed and kissed Dad’s nose.

The kitchen door swung open. Mom and Dulcie seemed to have made up after their quarrel, but Mom still looked tense, worried, uneasy.

“It’s good to see you, stranger.” Dad put Emma down and gave Dulcie a hug and a kiss. It was a long hug, I thought. I glanced at Mom. She was watching the two of them, but I couldn’t read her expression—except that I could tell she wasn’t happy.

“What brings you here?” Dad asked Dulcie.

“I’m in a group show at a D.C. gallery next fall,” Dulcie said. “Emma and I took the train down so I could talk to the owner. Since we were so close, I called Claire, and she picked us up at the station. We’re going back to New York tomorrow morning.”

Emma grabbed Dad’s hand. “Mommy wants Ali to baby-sit me at the lake, but Aunt Claire says she can’t.”

Dad turned to Dulcie and raised his eyebrows. “Sycamore Lake?”

“I drove to the cottage a couple of weeks ago,” Dulcie said. “Considering how long it’s been empty, it’s in pretty good shape. A couple of broken windows, a few leaks in the roof, and a dozen or more mice nesting in the cupboards.”

Dulcie glanced at Mom. “A trap will take care of the mice, and I’ve hired a contractor to fix everything else. By the time he’s done, Gull Cottage will have electricity, indoor plumbing, fresh paint inside and out, a new roof—and the old boathouse will be my studio.”

“In other words, it’ll be better than new.” Dad turned to Mom. “So why can’t Ali baby-sit Emma?”

“You know I hate the lake.” Mom’s voice rose a few notches, tense, anxious. “Ali could drown, she could get Lyme disease from a deer tick, she could get bitten by a snake, she—”

“Oh, for heaven’s sake.” Ignoring Mom’s whimper of protest, Dad looked at me. “How do you feel about the idea, Ali?”

“I want to go,” I said. “Staci will be away all summer. I’m sick of the swimming pool and the softball team.” And of Mom watching me all the time, I wanted to add, keeping me on a leash, owning me. Instead, I said, “The lake would be fun—an adventure, something different.”

“Please, please, pretty please?” Emma begged. “I’ll be so lonely without Ali.”

“Let her go, Claire,” Dad said. “She loves Dulcie and Emma. And they love her.”

“I’ll take good care of Ali,” Dulcie put in. “I won’t let her or Emma run wild. I promise.”

“You’ll get absorbed in your painting and forget all about them,” Mom muttered.

Dulcie exhaled sharply, clearly exasperated. “I’ve had sole responsibility for Emma since she was a baby. Does she look neglected?”

The argument went on during dinner, which made it hard to enjoy the pasta topped with Dulcie’s special marinara sauce, concocted from her ex-husband’s Italian grandmother’s recipe.

“It’s the only good thing I ever got from that man,” Dulcie said. “Besides Emma, of course.”

Dad laughed and Mom allowed herself to smile, and then they returned to the argument. Round and round they went, saying the same things over and over again. Mom refused to give in: I was too young to leave home for a whole summer, too young to be responsible for Emma.

At the end of the meal, Dad laid his fork and knife on his plate and said, “I’ve heard enough. Ali’s a sensible, responsible girl. There’s absolutely no reason why she shouldn’t spend the summer at the lake.”

Mom put her coffee cup down and stared at him, obviously shocked. “Pete, please—”

Whatever she was about to say was drowned out by Emma’s shout of joy. “Hooray! Hooray!” She jumped up from the table and ran to hug Dad. “Thank you, Uncle Pete, thank you!”

I looked at Mom uneasily, taking in the defeated slump of her shoulders. “Say it’s okay,” I begged. “Say I can go and you won’t be mad.” Or hurt. Or betrayed. Or worried.

She wiped her mouth carefully with her napkin. “If it means so much to you, go.” Without looking at anyone, she rose from the table and began gathering the dinner plates. The set of her jaw and her jerky movements clearly showed her anger.

“Give me a break, Claire. Don’t get in one of your moods.” Dulcie picked up a few glasses and followed Mom into the kitchen.

Carrying the serving bowls, I trailed after them, with Emma close behind clasping a fistful of spoons and forks. She handed them to Mom, then ran off to the living room.

Without speaking to anyone, Mom began loading the dishwasher.

“It’s the silent treatment,” Dulcie whispered to me. “She inherited it from our mother—and perfected it.”

I turned away, unwilling to criticize Mom. Dulcie was right, of course—silence and tears were Mom’s weapons. But it made me uncomfortable to agree with my aunt. After all, I had no reason to complain. I’d won. I was going to Sycamore Lake.

Leaving Mom to clean up

, I followed Dulcie into the living room. Dad was reading The Lonely Doll to Emma in a sweet bumbling bear voice.

I perched on the arm of Dulcie’s chair. “Can I ask you something?”

“Sure, sweetie.” Dulcie pushed her hair back from her face. Her long dangly silver earrings swayed and her bracelets jingled. She smiled, waiting for me to speak.

“Well, a couple of months ago I found an old Nancy Drew book in a box in the attic. While I was leafing through it, a photograph fell out. It was of you and Mom at Sycamore Lake—I could see the water behind you.”

Dulcie smiled. “Your grandfather loved taking pictures. Every time you turned around, there he was, pointing a camera at you. They were usually awful. We thought he had a special ugly lens he used for our pictures.”

“There was another girl with you,” I said, “but all that shows is her shoulder and arm. The rest is torn off.”

“Another girl?” Dulcie shook her head, and her soft hair brushed my cheek. “We didn’t have any friends at the lake. Gull Cottage sits out on a point, all by itself. There were no other kids around—just your mother and me.”

“Grandmother wrote your name and Mom’s name on the back,” I went on, trying to make her remember. “She wrote the girl’s name, too, but only the first letter is still there—‘T.’”

“‘T’?” An odd look crossed Dulcie’s face. “Did you ask your mother about the girl?”

“I told her I didn’t remember.” Mom stood in the doorway, her hands clasped, staring solemnly at her sister.

“I don’t remember, either,” Dulcie said quickly.

“What did you do with the picture, Mom? Maybe if Dulcie saw it—”

“I threw it away,” she said. “It was old, torn, faded.” Without another word, she picked up a gardening book and began to read, her way of saying she was still in a bad mood.

Before I could ask another question, Dulcie scooped up Emma. “Time for bed.”

“But Uncle Pete is still reading about Edith and the bears,” she said.

“You know that story by heart, sweetheart.” Ignoring Emma’s further protests, Dulcie carted her off to the guest room.

Dad turned on the TV to watch one of his favorite crime shows. It looked as if no more would be said about “T” that night.

4

After Dulcie and Emma went back to New York, Mom nursed her bad mood for weeks. She refused to take me shopping for summer clothes, so I tagged along with Staci and her mother. She wouldn’t talk about the lake or give me any baby-sitting tips. She spent almost all her time working in the garden, down on her hands and knees, weeding till her knuckles bled, watering and fertilizing, rearranging plants, adding new ones. Just to avoid me, I thought.

Even Dad found it hard to be patient with her, especially after she changed her mind about driving me to the lake.

“If Dulcie wants Ali to baby-sit, she can pick her up and drive her to Maine herself,” she told him.

He stared at her. “But, Claire, what about our plans to spend a few days on the coast?”

“I can’t leave the flowers. They’ll dry up. The weeds will take over.” Mom folded her arms tightly across her chest, her face taut with anxiety.

Dad’s frown deepened. “You realize that coming all the way down here to get Ali will add hours to Dulcie’s trip.”

Mom shrugged. “It was Dulcie’s idea to take Ali to the lake. Let her figure it out. She can always find another babysitter.”

Close to tears, I glared at Mom. “You’re still trying to keep me from going, aren’t you? Why don’t you just put me on a leash and tie me to a tree in the backyard?”

My outburst surprised Dad, but Mom nodded her head angrily. “You should’ve been Dulcie’s daughter—you’re more like her every day.”

“Good. Maybe I won’t grow up scared of everything, afraid to have fun, ruining everybody else’s fun.”

Too upset to reply, Mom ended the conversation by leaving the room.

Dad grabbed my shoulders and gave me a little shake, more to get my attention than anything else. “Don’t talk to your mother like that. Can’t you see you’re hurting her?”

I wanted to say Mom was hurting me, but Dad had already followed her out of the room. She’s not having a nervous breakdown, I shouted silently. She’s just crying because she can’t think of anything else to do.

I sighed and grabbed an apple from the bowl on the counter. Living in this house was good practice for crossing a minefield. If you weren’t careful, you could set off explosions with every step you took.

While I ate my apple, I stared out the kitchen window at the neighbor’s dog, tied to his tree. He lay in the dirt, his nose on his paws—totally bored, I was sure, but safe.

The day I left, Mom refused to get out of bed, claiming she had a migraine, the worst she’d had in over a year. Dad pulled the blinds to darken the room and sat with her for a while, reading a book as she dozed, another way to avoid talking.

When Dulcie arrived, Mom didn’t feel well enough to see her, so we said our goodbyes in her bedroom. “You don’t have to stay at the lake if you’re unhappy or homesick,” she whispered. “If anything scares you or worries you, call us. Your father will come get you.”

“Don’t worry. Everything will be fine,” I assured her.

Mom squeezed my hand. “I know you think I’m too protective,” she said, “but I want to keep you safe. You’re so young. You don’t know the terrible things that can happen, how quickly one’s life can change.”

“What do you mean?”

She closed her eyes. “My head hurts. I can’t talk anymore.”

I leaned over and kissed her gently. “I’ll be careful in the water,” I promised, “and I’ll take good care of Emma. Please don’t worry. I love you and I’ll miss you.”

Keeping her eyes closed, Mom said, “I love you, too.”

On the way downstairs, I asked Dad if the migraine was my fault.

“Of course not,” he said. “It’s tension, anxiety . . .”

Then it is my fault. I caused the tension and anxiety, didn’t I? I pushed the guilty thought away. Mom often had migraines. I couldn’t be blamed for all of them. Maybe this one, though.

Moments later, Emma was hugging me, squealing with delight, and Dulcie was assuring Dad she’d drive carefully and keep a close eye on me all summer.

Dad wedged my suitcase and bag of books into the van. I belted myself in the front seat, and Dulcie secured Emma in the back seat.

As I waved goodbye to Dad, I thought I saw a hand raise the blind in my parents’ bedroom. Mom must have felt well enough to watch her sister take me away for the summer.

The ride to Maine seemed to last forever—one boring interstate after another, dodging trucks, passing cars and motorcycles, stopping a couple of times at fast-food places for hamburgers and fries. Not what she usually ate, Dulcie assured me, but the quickest way to fill our stomachs.

Late in the afternoon, we left the last interstate and followed a network of roads, each narrower and more winding than the one before.

Emma leaned over the seat. “Are we almost there?”

Dulcie nodded. “See that tree? The one with the long limb like a trunk sticking out over the road? Claire and I called it the elephant tree. We’ll be at the cottage soon.”

A few minutes later, Dulcie slowed down and pointed out a little white store by the side of the road. Its windows were boarded up and a weather-beaten sign over the door said, OLSON’S. Weeds grew in the parking lot, and a row of seagulls perched on the roof.

“Claire and I used to ride our bikes all this way for home-made ice cream—the best chocolate I ever tasted.” Dulcie sighed. “Too bad it’s closed.”

Soon after, she said, “It’s the next left, just past that patch in the asphalt that looks like a bear. See? There’s the sign for Gull Cottage.” She pointed at a neatly lettered arrow-shaped board nailed to a tree. Below it was a mailbox, its door down, empty.

Dulcie turned onto a one-lane dirt road and we headed into the woods. The setting sun shot golden beams through the trees, but the light was dim and greenish, almost as if we were underwater.

We rounded a curve, and there it was, a small cottage sheltered by tall trees. The clapboards had a fresh coat of blue paint, and the steep roof was newly shingled. The lake itself was down a flight of wooden steps. I could see a dock and a small building beside it. Beyond a curve of sandy beach was the water, dark in the early evening light, stretching out to the horizon.

“It looks almost exactly the same,” Dulcie said. “Joe did a great job.”

With Emma close behind, I followed Dulcie across a deck and through the back door. I don’t know exactly what I’d expected—cobwebs and dust, stale air, maybe a gloomy, spooky atmosphere—but the cottage was bright and airy. Blue checked curtains hung at the kitchen windows, and the cabinets had been painted a sunny yellow, the walls pale blue, the table and chairs bright blue. The stove and refrigerator were a brand-new dazzling white.

“The old ones were antiques,” Dulcie said. “Plus they didn’t work.”

She led us into the living room, which was furnished with a pair of soft armchairs and a matching sofa sagging beneath faded flowered slipcovers. A big stone fireplace took up one whole wall, and windows with a view of the lake took up another wall. Shelves full of books and board games covered the third wall from floor to ceiling.

“The cottage was filthy when I saw it in April,” Dulcie said. “Joe hired a cleaning crew to scrub and vacuum. They got rid of spiders, squirrels, mice, and a family of raccoons living under the deck.”

“But they didn’t hurt them, did they?” Emma asked, her voice full of concern.

“Of course not, sweetie. They caught the mice and squirrels and raccoons in Havahart traps and let them go in a nice part of the woods, and they picked up the spiders very gently in tissue and carried them outside.”

“That’s good.” Emma looked pleased. “If they come back, they can sleep in my room. I won’t mind.”

Mister Death's Blue-Eyed Girls

Mister Death's Blue-Eyed Girls The Ghost of Crutchfield Hall

The Ghost of Crutchfield Hall Hear the Wind Blow

Hear the Wind Blow Time of the Witch

Time of the Witch The Girl in the Locked Room: A Ghost Story

The Girl in the Locked Room: A Ghost Story All the Lovely Bad Ones

All the Lovely Bad Ones One for Sorrow

One for Sorrow Deep and Dark and Dangerous

Deep and Dark and Dangerous Tallahassee Higgins

Tallahassee Higgins Promises to the Dead

Promises to the Dead Took: A Ghost Story

Took: A Ghost Story Following My Own Footsteps

Following My Own Footsteps Wait Till Helen Comes: A Ghost Story

Wait Till Helen Comes: A Ghost Story Where I Belong

Where I Belong The Spanish Kidnapping Disaster

The Spanish Kidnapping Disaster Look for Me by Moonlight

Look for Me by Moonlight The Old Willis Place

The Old Willis Place Closed for the Season

Closed for the Season As Ever, Gordy

As Ever, Gordy Anna on the Farm

Anna on the Farm The Doll in the Garden

The Doll in the Garden Daphne's Book

Daphne's Book Witch Catcher

Witch Catcher The Gentleman Outlaw and Me--Eli

The Gentleman Outlaw and Me--Eli Wait Till Helen Comes

Wait Till Helen Comes Took

Took A Haunting Collection

A Haunting Collection Anna All Year Round

Anna All Year Round The Girl in the Locked Room

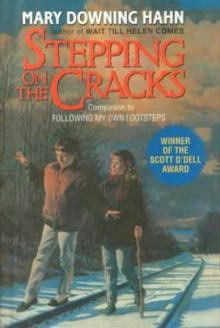

The Girl in the Locked Room Stepping on the Cracks

Stepping on the Cracks