- Home

- Mary Downing Hahn

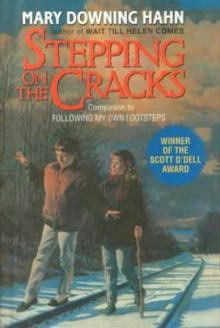

Stepping on the Cracks

Stepping on the Cracks Read online

Stepping on the Cracks

Mary Downing Hahn

* * *

CLARION BOOKS • NEW YORK

* * *

Clarion Books

a Houghton Mifflin Company imprint

215 Park Avenue South, New York, NY 10003

Text copyright © 1991 by Mary Downing Hahn

All rights reserved.

For information about permission to reproduce

selections from this book, write to Permissions,

Houghton Mifflin Company,

215 Park Avenue South, New York, NY 10003

Printed in the USA

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Hahn, Mary Downing.

Stepping on the cracks / by Mary Downing Hahn,

p. cm.

Summary: In 1944, while her brother is overseas fighting in World

War II, eleven-year-old Margaret gets a new view of the school bully

Gordy when she finds him hiding his own brother, an army deserter,

and decides to help him.

ISBN 0-395-58507-4

[1. World War, 1939–1945—United States—Fiction. 2. Bullies—

Fiction.] I. Title.

PZ7.H1256St 1991 91-7706

[Fic]—dc20 CIP AC

QUM 20 19 18 17

* * *

This book is dedicated to the Downing family:

Especially to the memory of

my father, Kenneth Ernest Downing (1904–63),

and my uncles:

Dudley Downing, who was killed in Belgium in 1944 and

awarded the Distinguished Service

Cross for exceptional heroism in combat,

and

William Alexander Downing, who survived the

Battle of the Bulge in the Ardennes forest.

* * *

1

One afternoon in August, Elizabeth and I were sprawled on my front porch playing an endless game of Monopoly (or Monotony, as Elizabeth called it).

"Your turn," I announced. I'd just passed the bank and picked up two hundred dollars to add to my pile of paper money. For once, I was definitely winning.

When she drew a card that told her to go to jail, Elizabeth threw it down. She was already broke and in debt to me because I owned Atlantic Place and her man kept landing on it. Every time that happened, she had to hand me five hundred dollars rent.

Elizabeth scowled at her little pile of money and ran a hand through her blonde hair, putting a few more tangles in it. Then she poked the Monopoly board with one bare foot, just hard enough to slide the expensive hotels and cottages off my property. Our little men rolled across the porch, and some of the paper money fluttered away.

"Let's go somewhere before I keel over and die of boredom," Elizabeth said.

Ignoring her, I crawled around, gathering up the playing pieces. Unlike Elizabeth, I was perfectly content to spend the rest of the day where we were. The heat had melted my bones away, and I felt as limp as a rag doll. "It's too hot," I muttered, "to do anything."

But Elizabeth wasn't listening. Climbing to the porch railing, she grinned down at me. "Dare me to jump?"

Before I could say yes or no, Elizabeth hollered "Geronimo!" Arching her body, she flew through the air like a circus acrobat and landed gracefully on the grass. "Come on, Margaret," she shouted.

Not wanting to be a sissy baby, I held my breath, leapt off the railing, and hit the ground so hard I knocked the scab off my skinned knee. As I spit on my finger to wipe the blood away, Elizabeth hopped down the sidewalk.

"Step on a crack," she yelled, "break Hitler's back! Step on a crack, break Hitler's back!"

Despite the heat, I stamped along behind Elizabeth. Under my bare feet, I saw Hitler's face on the cement—his beady eyes, his mustache, his mean little slit of a mouth. I shouted and pounded him into the pavement, and every time I said his name it was like swearing. It was Hitler's fault my brother Jimmy was in the army, Hitler's fault Mother cried when she thought I wouldn't hear, Hitler's fault Daddy never laughed or told jokes, Hitler's fault, Hitler's fault, Hitler's most horrible fault. I hated him and his Nazis with a passion so strong and deep it scared me.

Behind me, the screen door opened, and Mother called, "Margaret, how often do I have to tell you not to jump like that?" She frowned at me from the porch. "You won't be happy till you ruin your insides, will you?"

Elizabeth grinned at Mother, her eyes squinted against the sun. "Hi, Mrs. Baker," she said.

Mother looked at Elizabeth, but she didn't return her smile. "What was all that shouting?" she asked. "You two were making enough noise to wake the dead."

"It's a game I thought up," Elizabeth said. "Step on a crack," she yelled, jumping hard on the sidewalk to demonstrate. "Break Hitler's back!"

"When I was your age, we said, 'Step on a crack, break your mother's back,'" Mother told her. "We tried hard not to step on the cracks."

"That was before Hitler," Elizabeth said. "The world was different then."

Mother leaned against the door frame, her arms folded across her chest, and sighed. "Yes," she said, agreeing for once with Elizabeth. "I guess it was."

For a moment or two, no one said anything. I saw Mother glance at the blue star hanging in our living room window, and I knew what she was thinking. That star meant Jimmy was overseas fighting a war Hitler started. There was a star in Elizabeth's window, too, because her brother Joe was in the Navy. That summer, there were stars in lots of windows in College Hill, and not all of them were blue. Some, like the one across the street in the Bedfords' window, were gold. The Bedfords' son Harold had been killed in Italy last summer. That was what gold meant.

In the silence, I heard a surge of organ music from our radio. It was time for "The Romance of Helen Trent," one of Mother's favorite soap operas. As she opened the screen door to go inside, Mother paused and looked at Elizabeth. "Where are you two going this afternoon?" she asked.

"Bike riding," Elizabeth said, as if I'd already agreed.

"Don't you dare take Margaret down that hill on Beech Drive," Mother said. "You almost killed yourselves last time."

But she was speaking to the air. Elizabeth had already darted through a gap in the hedge between our houses. In a few seconds she was back with her brother Joe's bike, an old Schwinn. The crossbar was so high Elizabeth could barely straddle it, but she rode it anyway.

Taking my seat on the carrier over the rear wheel, I held on to Elizabeth's waist as she pushed off across the grass. Wobbling till she picked up speed, she pedaled along Garfield Road toward Dartmoor Avenue.

The hot sunlight poured down through the green leaves, dappling the dirt road with a lacy pattern of shadows, and the Schwinn's big balloon tires bounced over the ruts. Mrs. Bedford waved to us from her front porch, Mrs. Porter smiled at us from her side yard, where she was hanging her laundry out to dry, and old Mr. Zimmerman nodded to us from the corner. His little dog, Major, barked and wagged his tail. On a cooler day, he might have chased us.

Through the open windows of every house, we heard snatches of radio shows. The voice of Helen Trent and the happy song advertising Rinso laundry soap followed us down the shady street. College Hill was so peaceful, it was easy to forget the war. In fact, Helen Trent's love life seemed more real than the battles our parents talked about. Although it was 1944, and World War II had been going on for over two and a half years, nothing had happened to change our lives. Except for Jimmy's absence and a lot of shortages, everything was the way it had always been.

With me clinging behind her, Elizabeth crossed the trolley tracks and pedaled past the school, sleeping like a brick giant in the summer sunlight. Soon enough its green doors would

open wide and swallow us up, but for now we were safe. Three more weeks of freedom before we faced sixth grade and the dreaded Mrs. Wagner.

Elizabeth turned a corner, and we glided down Forest Way toward Beech Drive. The road here was paved, and Elizabeth pedaled faster, zooming past big brick houses with mossy slate roofs. The bike tires made a hissing sound on the gritty surface of the macadam, and a dog barked at us from behind a picket fence. Otherwise, it was very quiet.

Not far from Beech Drive, Elizabeth's back tensed and she braked hard. "Oh, no," she said. "Not him."

Looking over her shoulder, I saw what she saw. Just ahead, three bicycles blocked the street. Gordy and his friends, Toad and Doug, were waiting for us. From two blocks away, I could see the sneers on their faces.

If there was anybody in College Hill I hated more than Gordy Smith, I didn't know who it was. Way back in kindergarten, the very first time he ever saw Elizabeth, Gordy had walked right up to her and pulled her hair as hard as he could. Being Elizabeth, she'd punched him in the stomach. They'd been enemies ever since. Because I was Elizabeth's best friend, I was on her side against Gordy.

For some reason, Gordy was meaner than ever this summer. You'd think he was a Nazi, the way he acted, fighting with everyone and picking on girls and little kids. The very sight of him scared me to death, and I scrunched down behind Elizabeth.

"Turn around," I whispered, squeezing her waist to get her attention. "Go back the way we came. Maybe Gordy won't bother us."

Elizabeth tried to swerve down a side street, but, with me behind her, she wasn't fast enough. In seconds, the three boys had us surrounded.

"Well, well, if it isn't Little Lizard," Gordy said. He was wearing a dented Civil Defense warden's helmet, a striped jersey, stretched at the neck and several sizes too small, and old knickers held up with suspenders. Pure meanness shone out of his gray eyes.

Elizabeth gripped the bike's handlebars so tightly her knuckles turned white. "Don't call me Lizard," she said. "My name is E-liz-a-beth!"

"I'll call you anything I like, Lizard." Gordy grabbed her handlebars with one hand and smirked at her. Then he looked at me.

"Hey, Baby Magpie. Cat got your tongue as usual?" Grabbing one of my braids, he tugged just hard enough to pull me toward him. As I tried to yank free, he laughed and let me go, and I bounced back behind Elizabeth.

In the silence, Doug blew a big bubble, popped it loudly, and sucked it slowly back into his mouth. He was short, and his skin was almost exactly the same color as the dirty blonde hair that hung in his eyes.

"Hey, Gordy," he said. "You better listen to E-liz-a-beth. She's one tough cookie."

Toad didn't say anything. He just looked at Gordy and giggled. In the heat, his face was as red as his hair, and his freckles had gotten so dark he looked like a fat leopard.

Gordy leaned toward Elizabeth and said, "We just got a letter from Donald. He's blowing Nazi planes out of the sky." He pretended he was pointing a gun at her. "Ackety, ackety, ack."

Some of his spit shot past Elizabeth and sprayed my cheek. I made a face and rubbed it away, but Gordy didn't notice.

"I bet your brother hasn't killed half as many Japs," Gordy said to Elizabeth. "Donald's the best gunner in the whole army. When Toad and Doug and me are old enough, we're going to be just like him. We'll kill lots of Nazis. Maybe even Hitler himself."

"You dumbo, the war will be over way before you grow up," Elizabeth said scornfully.

Gordy shoved his face close to hers, and Elizabeth drew back, tense again. "Girls don't know diddley squat about war, so don't act smart, Lizard."

"Let go of my bike," Elizabeth said.

Gordy shook the handlebars. "This is Joe's bike."

"Well, let go of it anyway!" Elizabeth tried to pry Gordy's fingers off.

"Oh, Dougie," he yelped, "help me. Lizard's hurting me so bad."

They all laughed and moved their bikes even closer to us. Gordy leaned toward Elizabeth again. He was so near, I could smell peanut butter and something less pleasant on his breath. His black hair hung in his eyes, he had a pimple in the corner of his mouth, and his neck was circled with a dark ring of dirt. "Give me a kiss, Lizard," he said. "Then I'll let you go."

"I'd rather kiss a pig," Elizabeth said. "They smell better."

When Gordy leaned even closer, puckering his lips and making loud smooching sounds, Elizabeth pulled back, bumping her head against mine. "Get away from me," she yelled. "You stink."

Just as Gordy grabbed Elizabeth's arm, Mrs. Fuller stepped out on the front porch of the house on the corner. "That's enough, Gordon Smith," she called. "You leave those girls alone."

"Why don't you mind your own beeswax?" Gordy yelled at her. "Old busybody." But he dropped Elizabeth's arm. Then, spinning his tires on loose pebbles, he zoomed off down the street with Doug and Toad flanking him.

"Hey, Lizard," he called back, "you got away this time, but there's always a next time. I'll be looking for you!"

Mrs. Fuller stood on her porch and watched the boys disappear around a comer, laughing and yelling insults at her, Elizabeth, and me.

"I don't know what the world's coming to," she said to no one in particular. "Children run wild these days, with no respect for anyone." Frowning at Elizabeth and me, she went inside, letting her screen door slam behind her.

"I wish Gordy was old enough to get drafted," I said as Elizabeth began pedaling toward home. "Then we wouldn't ever have to see him again."

"Me, too," Elizabeth agreed. "I hate him so much I wouldn't care if the Nazis dropped a bomb on him. Kapow!"

"You sure told him off," I said.

She grinned at me over her shoulder. "I should've slapped him. In the movies, Joan Crawford always wallops guys who get fresh with her."

Standing up, Elizabeth pumped harder. A little breeze fanned my cheeks, but rivulets of sweat ran down her backbone, streaking her blue jersey. Resting on the seat, Elizabeth let the bike coast, and we rolled silently around the corner and down Garfield Road.

Glancing behind me at the empty street, I hoped we wouldn't see Gordy again till school started. But in a town as small as College Hill, it's hard to avoid people, especially if they're looking for you.

2

When Mother saw me coming up the back steps, she said, "Sit down and rest, Margaret. You look like you're about to have heat stroke."

Taking the glass of ice water she handed me, I perched on the kitchen counter and watched her iron. She had one of Daddy's tan work shirts spread out on the board, so stiff with starch she had to pry it off when she was done. The little Philco radio on top of the refrigerator was tuned to "The Guiding Light," another one of her favorite soap operas.

As the episode ended, Mother turned to me. "Where did you and Elizabeth go today?"

"Just around. Not very far." I drank the last of my water and started crunching an ice cube. "We saw Gordy," I added. "He's so ugly. Elizabeth and I hate his guts."

Mother looked up from a pair of Daddy's work pants. "Don't talk like that, Margaret," she said.

"Why not? He's horrible and disgusting, and he spit all over me."

Mother frowned and pressed the iron on Daddy's pants so hard they steamed, releasing the sweet smell of starch mixed with a kind of burning odor. Lifting the iron, she frowned at the tiny singe mark on the cloth. "Ladies don't use words like 'guts,'" she said. "Do you want people to think you have no manners?"

"Well, I don't think it's good manners for somebody to spit on another person."

Mother sighed and brushed a strand of gray hair out of her eyes. "Try to have a little sympathy for people like Gordy," she said. "Suppose you lived the way he does. Or had a father like Mr. Smith."

I swung my heels against the cabinet door and watched Mother sprinkle more water on Daddy's pants. I'd never met Gordy's father, but I'd learned a lot about him from Elizabeth. Her father was a policeman, and he'd arrested Mr. Smith more than once for being drunk and disorderly. Elizabeth wasn't supposed to kno

w things like that, but, being a good listener, she heard plenty of stories about the nights Mr. Smith got drunk at the Starlight Tavern and started fights. In Mr. Crawford's opinion, Mr. Smith was a no-good bum, and he wished he'd take his family and get out of town. "Poor white trash, the lot of them," Mr. Crawford said.

A couple of times, when Elizabeth and I were feeling brave, we'd ridden Joe's bike down Davis Road, right past Gordy's house, hoping to get a glimpse of Mr. Smith. The yard was full of broken toys and all sorts of junk. Grubby little Smiths, smaller versions of Gordy, yelled at us from behind the fence. Sometimes they even threw things.

But I didn't think Gordy's house or his father were any excuse for his behavior. He was mean and ugly and, no matter what Mother had to say about my choice of language, I hated his guts.

"Margaret, please stop kicking the cabinet," Mother said. A pair of my shorts lay on the ironing board, and she was frowning at the grass stains on the seat.

"Can't you be more careful?" she asked. "It's hard enough these days just replacing the things you grow out of. It makes me mad to see you ruin perfectly good clothes."

"I'm sorry," I said. Putting my empty glass in the sink, I left the kitchen. Sometimes I couldn't please my mother no matter what I said or did. It seemed to me she'd been in a bad mood ever since Jimmy was drafted.

***

A few hours later, I was sitting on the front porch looking at cartoons in the Saturday Evening Post. Hearing footsteps, I looked up and saw Daddy trudging toward me. He'd walked two blocks from the trolley stop, and his forehead was beaded with perspiration. Even though he worked in Washington fixing other people's Buicks, we couldn't afford a car ourselves. Gas and tires were just too expensive.

Grunting his usual hello, Daddy walked past me without even giving me a pat on the head. As the screen door shut behind him, I heard him ask Mother if we'd gotten a letter from Jimmy.

I sat there for a few minutes, staring at the magazine cover. Daddy was going to be disappointed. I'd waited all morning for the mail, hoping for a letter, but Mr. Murphy had handed me the telephone bill, the electric bill, and the magazine I was holding now. He'd felt bad, I could tell. It must be awful to walk up people's sidewalks knowing you haven't got the letters they're waiting for.

Mister Death's Blue-Eyed Girls

Mister Death's Blue-Eyed Girls The Ghost of Crutchfield Hall

The Ghost of Crutchfield Hall Hear the Wind Blow

Hear the Wind Blow Time of the Witch

Time of the Witch The Girl in the Locked Room: A Ghost Story

The Girl in the Locked Room: A Ghost Story All the Lovely Bad Ones

All the Lovely Bad Ones One for Sorrow

One for Sorrow Deep and Dark and Dangerous

Deep and Dark and Dangerous Tallahassee Higgins

Tallahassee Higgins Promises to the Dead

Promises to the Dead Took: A Ghost Story

Took: A Ghost Story Following My Own Footsteps

Following My Own Footsteps Wait Till Helen Comes: A Ghost Story

Wait Till Helen Comes: A Ghost Story Where I Belong

Where I Belong The Spanish Kidnapping Disaster

The Spanish Kidnapping Disaster Look for Me by Moonlight

Look for Me by Moonlight The Old Willis Place

The Old Willis Place Closed for the Season

Closed for the Season As Ever, Gordy

As Ever, Gordy Anna on the Farm

Anna on the Farm The Doll in the Garden

The Doll in the Garden Daphne's Book

Daphne's Book Witch Catcher

Witch Catcher The Gentleman Outlaw and Me--Eli

The Gentleman Outlaw and Me--Eli Wait Till Helen Comes

Wait Till Helen Comes Took

Took A Haunting Collection

A Haunting Collection Anna All Year Round

Anna All Year Round The Girl in the Locked Room

The Girl in the Locked Room Stepping on the Cracks

Stepping on the Cracks