- Home

- Mary Downing Hahn

Following My Own Footsteps

Following My Own Footsteps Read online

Following My Own Footsteps

Mary Downing Hahn

* * *

Clarion Books

New York

* * *

Clarion Books

a Houghton Mifflin Company imprint

215 Park Avenue South, New York, NY 10003

Copyright © 1996 by Mary Downing Hahn

Text is 11/15-point Meridien

All rights reserved

For information about permission to reproduce selections

from this book, write to Permissions, Houghton Mifflin Company,

215 Park Avenue South, New York, NY 10003

For information about this and other Houghton Mifflin

trade and reference books and multimedia products,

visit The Bookstore at Houghton Mifflin on the World Wide Web at

http //wwwhmco com/trade/

Printed in the USA

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Hahn, Mary Downing

Following my own footsteps / by Mary Downing Hahn,

p cm

Summary In 1945, Gordy's grandmother takes him and his family

into her North Carolina home after his abusive father is arrested,

and he just begins to respond to his grandmother's loving discipline

when his father returns.

ISBN 0-395-76477-7

[1 Family violence—Fiction 2 Parent and child—Fiction

3 Grandmothers—Fiction 4 World War, 1939–1945—

United States—Fiction] I Title

PZ7 H1256Fn 1996

[Fic]—dc20

95-50144

CIP

AC

QW 10 9 8 7 6 5 4

* * *

In memory of Helen Shelton,

mentor and friend

One

"Mama," I said, letting my voice rise higher than the wind in the treetops, "Mama, come on, hurry up. I hear the train!"

I tugged at her coat sleeve, trying to pull her along. If we missed the morning train, Mama might change her mind before the next one came. Instead of leaving, she'd head back home, if you can call it that, and wait for the cops to let the old man go. She'd forgive him. After all the evil he'd done to us, she'd take him back. And we'd be stuck forever down at the end of Davis Road. We'd never get out of College Hill. Never get away from the old man.

"Let go of me, Gordy," Mama said, shaking free of me. "Leave me be. We have plenty of time." She was carrying my littlest brother Bobby and towing Ernie by the hand. Victor lagged behind all of us, struggling to carry a grocery bag stuffed with his belongings.

"Wait for me," he whined every step of the way and of course Mama did, standing there on the muddy road, her coat blowing open in the cold February wind. Not even telling Victor to get a move on. Just waiting as still as a statue.

"The train's blowing for the Berwyn crossing," I said. "College Hill's next and we still got four blocks to go."

My little sister June ran to the edge of the railroad bank and peered down the track. "It's coming, Mama, it's coming," she shrieked. "I see the smoke!"

"Wait, wait, don't go without me!" Victor ran toward us, trying to catch up. His old teddy bear bounced out of the sack and splashed into a mud puddle.

As quick as I could, I grabbed the bear and wiped him on my jacket. "Don't start crying, Victor, not now," I said. "We don't have time for the weeping willies."

He was already sniffling but I took his hand and dragged him toward the train station. "Choo-choo's coming, Victor!"

That cheered him up a bit, even made him walk a little faster. He'd been wanting to ride a train all his life. For that matter, so had I. I used to lie in bed at night, listening to the old man rant and rave in the living room, and daydream about hopping one of the freights that thundered by the house.

On really bad nights, I'd sneak out the bedroom window and walk down to the railroad tracks. Safe from the old man's fists, I'd sit in a tree and watch the trains go by. In the dark, the locomotives were a gorgeous sight, shooting sparks like dragons and hiding the stars with smoke. They roared and rumbled, making the rails bounce under their weight, and their whistles just about split the sky in half. Only trouble was, they went by too fast for me to grab hold of a boxcar and jump on the way hoboes do.

After a train passed, I'd sit there all by my lonesome, listening to the whistle blow for the next crossing and wondering where the train was going—New York, Detroit, Chicago, maybe out west to California and the redwood forest. Or down south to the Gulf Stream waters, like that song we sang in school.

I never sang with the other kids, of course. While they bellowed, I just sat there drawing Nazi bombers and stuff, but deep in my heart I knew all the words. And what they meant. Someday I, Gordon P. Smith, planned to travel that ribbon of highway under the endless skyway. I'd roam and ramble and follow my own footsteps, I'd leave all those snobby College Hill kids and teachers in the boring Maryland dust and never look back.

But in real life, things don't happen the way you imagine. Instead of heading west by myself, I was going to North Carolina on an ordinary old passenger train with my family. Or what was left of it. As I've said, the old man was in jail where, if you ask me, he'd belonged for years. My brother Donny was overseas fighting the Nazis and my brother Stuart was in an army hospital. That left Mama, June, and my three little brothers. June was six and not too bad for a girl. Victor was four, Ernie was three, and Bobby was two. They reminded me of puppies nobody'd bothered to train. In fact, Bobby wasn't even housebroken yet.

"Hurry, hurry!" June hollered. "The train's almost here, Mama!"

Mama didn't walk a bit faster. If anything she was slowing down, looking behind her every now and then as if she expected to see the old man coming after us.

June ran ahead, her skinny legs scissoring as she jumped mud puddles. She clutched her grocery bag so tight her dolly's head bounced up and down like a rubber ball. "I'll tell the train to wait for you," she yelled.

Like me, June wanted to get out of town before the old man found us. He'd be mad as hell, that's for sure. No matter what evil things he'd done before, nobody had called the cops, he'd never gone to jail. He'd just slept it off and then begged Mama to forgive him.

"I'll never drink another drop, Ginny," he'd say, all weepy and smelly and bleary-eyed, ugly as sin and no more believable than the devil himself.

But Mama would forgive him. Her black eye would fade to purple and green and yellow and then clean away, she'd use the perfume he gave her, she'd smile again. "You see, Gordy," she'd say. "This time your father means it. No more whiskey."

A month or so would pass, and then one night he'd come home grinning that lopsided grin and walking like the floor tilted under his feet. Somebody would say the wrong thing or look at him funny and he'd be slapping us around all over again.

I took Mama's arm to hurry her. She winced, and I let go, knowing I must have squeezed a sore place. "Let me carry Bobby," I said. "You can't handle him and that suitcase."

Bobby started wailing when I took him. Paying him no mind, I hurried to catch up with June. I knew for a fact Mama wouldn't let me get on the train with her baby unless she was with us.

Sure enough, when the locomotive came to a big steaming, huffing stop at the College Hill station, Mama climbed aboard just behind me. At last, I thought, we're getting out of town, just like a gang of outlaws leaving on a stagecoach. If any of my old enemies had been around, I'm sure they'd have cheered to see me go. But they were all in school, sitting in Wagner's room, looking at my empty desk and wondering when I'd be back.

"Never," I muttered as the train gave a jerk and started to move. "Never!"

&

nbsp; Two

Because of the war, the passenger car was jam-packed with soldiers and sailors. You can bet nobody looked happy to see us coming down the aisle. Mama had taken Bobby from me, and she was having trouble managing him and her big old suitcase. Ernie was hanging on to her leg, kind of bouncing along behind her and crying, of course. The rest of us followed like baby ducks, toting our grocery bags.

Somehow June and I managed to squeeze into a seat beside a fat lady who took up more than her share of space and sighed loudly when we sat down. Which is how most people react to our family. Just let us Smiths appear in public and the rest of the world curls up its toes and dies. Nobody likes us, not even strangers.

Anyhow, June and I were scrunched together so tight we couldn't breathe without poking each other. To make things worse, Victor sat on my lap, whining and wiggling and fussing. Across the aisle, Mama held Ernie on one knee and Bobby on the other, getting dirty looks from the soldier next to her.

Well, maybe I wouldn't have wanted to be sitting next to Mama, either. Even from my seat I could smell the load in Bobby's pants. Seemed like that kid wasn't ever going to learn to use a toilet.

After a few minutes, June tugged my arm. "Did Donny look like those soldiers when he left for the war, Gordy?"

I glanced at the guys she was pointing at. Most of them were talking loud and laughing even louder, wisecracking and telling jokes and smoking cigarettes till the air was so thick you could hardly breathe.

"Yeah," I said to June. "Donny looked just like them. Don't you remember?"

"He was tall," she said, frowning as if it was hard to recall even that much.

"Well, you were only about three when he left, not as big as Victor here." I nodded at my brother who was, thank the Lord, asleep. It struck me June wouldn't remember what Donny looked like if he got killed before the war was over. Neither would Victor or Ernie or Bobby. I was the only one besides Stu who'd remember him.

"Are they going to the war?" June asked, staring at the soldiers. "Are they going to fight Hitler like Donny?"

"Probably." I studied the soldiers again. Not all of them were joking and carrying on. Some of them sat by themselves, their noses pressed to the window like they were hoping to see a sign saying Hitler was dead, the war was over, they could go back home. They reminded me of Stu.

I looked at my sister, but she seemed to have lost interest in the soldiers. Pulling her dolly, a nearly bald, one-eyed wonder, out of her bag, she held it up so it could see out the window. "You're on the choo-choo train, Baby. We're going to Grandma's house."

June rocked the dolly and began singing, "'Over the river and through the woods to Grandmother's house we go.'"

The fat lady glanced at June and actually smiled. "I bet you love your granny, don't you?" she asked in one of those sugary-sweet voices grown-ups use when they speak to little kids like June.

June stopped singing and stared at the fat lady, who looked like a granny in a picture book. "I hope I love her," she said. "I didn't even know I had a grandma till Daddy went to jail and Mama called her on the phone and she said we could stay with her for a while."

The fat lady drew in her breath. "I see," she said, shifting a little closer to the window.

"Daddy got drunk. He beat up Mama and almost killed my brother Stu," June said as if it was something to brag about. "Daddy was mad 'cause Stu deserted from the army. Now Stu's in the hospital and Daddy's in jail and we're going over the river and through the woods to Grandma's house."

All the time June was babbling our family secrets, I was pinching her arm to shut her up. Finally she stopped talking and slapped my hand. "Quit that, Gordy!" To the fat lady she said, "I hope my daddy stays in jail forever and ever. He's a bad man and I hate him. Gordy hates him too."

The fat lady heaved herself to her feet and smoothed her dress. Clutching her purse, she began to inch past us toward the aisle.

"Are you going to the bathroom?" June asked. "Want us to save your place till you come back?"

Murmuring something about getting off the train at the next stop, the fat lady forced her way up the aisle, whacking a few soldiers with the suitcase she pulled down from the luggage rack.

"She was a nice lady," June said when the fat lady was gone.

"Why did you tell her about the old man?" I asked. "For the Lord's sake, June, there's no sense telling strangers your daddy's in jail."

"It was all I could think of to say." Spitting on her finger, June began cleaning her dolly's face. "Baby, you're all dirty! How often have I told you not to play in the mud?" She shook the doll so hard her head almost fell off. "Bad, bad Baby!"

I leaned back in my seat. Now that the fat lady was gone, I could actually see out the window. We'd passed through Washington while June was telling the whole train about the old man's current address, so I figured we must be in Virginia now. At first, the scenery looked pretty much the same as Maryland. Woods, still bare and brown from winter. A farm every now and then. Horses running from the train. Cows standing around looking bored. Towns, houses, churches, schools, playgrounds.

It was warm and stuffy in the car, and I kept dozing off only to wake up every time the train stopped, which was pretty often. I hadn't slept very well the night before. I'd been scared to close my eyes for fear the old man would come home and start beating on us again. Kept seeing his ugly face, feeling his fists, hearing his voice cursing Stu, cursing Mama, cursing all of us, even Bobby who'd never done anything except get born.

"SOB," I muttered, clenching my own fists. "Hit me again and I'll kill you, I swear I will."

Beside me, June gave a little jump in her sleep. "Don't," she mumbled. "Don't."

I picked up poor old Baby, who'd tumbled to the floor, and laid her beside my sister. Trying to stay awake, I pressed my face against the cold window and watched the farmland streak past. Far away and blue against the sky I saw mountains, the first I'd ever seen. There was no snow on the tops, but they were taller than the hills I was used to.

It struck me this was the farthest I'd ever traveled in my whole entire life. The world seemed bigger here, not so closed in by fences and hedges and houses. The words of that song floated through my head again—the ribbon of highway, the endless skyway, the golden valley, the diamond desert. At last, I was beginning to roam and ramble. There was no telling how far I'd go or what I'd see. North Carolina was just the first step.

I must have dozed off again because the next thing I knew June was shouting in my ear, "We're almost there, we're almost there. The conductor said Grandville's the next stop!"

I shifted Victor from my lap to the floor, steadying him with my legs. Darned if he hadn't wet his pants and mine, too.

While I was wondering what I was going to do about it, June squeezed my arm. "Gordy, do you suppose they named Grandville after Grandma?"

"What are you talking about? Her name's Aitcheson, not Grand."

"Her name's Grandma," June said, scowling at me. "And the town is called Grandville."

I started to laugh, but then I remembered how easy it was to hurt June's feelings. Across the aisle, Bobby was already crying and Ernie was tuning up. Victor was whining his stomach hurt. I didn't want to get off the train with everybody bawling but Mama and me.

"Maybe you're right, Junie," I said. "That would make Grandma a real important person, wouldn't it?"

June nodded and smoothed her dress. "Do I look pretty?"

"Sure you do," I lied. The truth was, her hair was ratty with tangles, her dress was stained with the apple juice she'd spilled at breakfast, and she had that pale, sickly look she gets when she's tired.

"That's good," she said. "I want Grandma to think I'm a pretty little girl. I want her to love me."

To my relief, I didn't have to say anything because the conductor came down the aisle, bellowing, "Grandville, everybody off for Grandville."

By the time the train stopped, we were standing at the door, ready for our first look at Grandma and Grandville both. I

hoped she and the town were ready for us.

Three

I guess I'd expected Grandma to be a beaten-down old woman, poor and shabby like us, but the tall white-haired lady walking toward us looked like a queen.

Junie tugged at my jacket. "I told you she was grand, didn't I? Didn't I, Gordy?"

I nodded, holding my bag of clothes so it hid the wet spot Victor had left on my pants. Not that anyone was paying a speck of attention to us kids. Grandma and Mama stood face to face, staring at each other. I swear they looked like enemies meeting on a battlefield. No hugs, no kisses, no smiles, no glad words. Just eyeball-to-eyeball silence.

Mama was the first to look away, but Grandma was the first to speak. "For pity's sake, stand up straight, Virginia," she said, "and get that hangdog look off your face."

Mama didn't raise her head. She ran one hand through her hair and kept on staring at the station platform. Not one word did she say.

Ernie and Bobby more than made up for Mama's silence by bawling like calves. Victor just stood there, picking his nose as if he didn't have all his buttons. When I slapped his hand, he called me a name I knew Grandma wouldn't like. Then he hauled off and kicked me.

While I tried to make Victor behave, I glanced at June. She was standing up straight and tall, waiting for Grandma to notice her and smiling so hard it hurt to look at her. If you ever saw a puppy at the pound, that's what June reminded me of. Pale and dirty and skinny but hopeful. If she'd had a tail, she'd have been wagging it to beat the band.

Mama pulled us forward one at a time and introduced us. It seemed to me Grandma was more shocked than happy to meet all us kids. Mama hadn't seen her or talked to her for years, not since she'd eloped with the old man and scandalized the whole town. Now she'd come home. Maybe she hadn't said exactly how many kids she was bringing with her.

"And this is Gordy," Mama said, nudging me forward.

Before Grandma said anything, she looked behind me as if she feared there might be a few more grandchildren back there. Then she shook my hand and said she was glad to meet me, which was what she'd said to everybody else.

Mister Death's Blue-Eyed Girls

Mister Death's Blue-Eyed Girls The Ghost of Crutchfield Hall

The Ghost of Crutchfield Hall Hear the Wind Blow

Hear the Wind Blow Time of the Witch

Time of the Witch The Girl in the Locked Room: A Ghost Story

The Girl in the Locked Room: A Ghost Story All the Lovely Bad Ones

All the Lovely Bad Ones One for Sorrow

One for Sorrow Deep and Dark and Dangerous

Deep and Dark and Dangerous Tallahassee Higgins

Tallahassee Higgins Promises to the Dead

Promises to the Dead Took: A Ghost Story

Took: A Ghost Story Following My Own Footsteps

Following My Own Footsteps Wait Till Helen Comes: A Ghost Story

Wait Till Helen Comes: A Ghost Story Where I Belong

Where I Belong The Spanish Kidnapping Disaster

The Spanish Kidnapping Disaster Look for Me by Moonlight

Look for Me by Moonlight The Old Willis Place

The Old Willis Place Closed for the Season

Closed for the Season As Ever, Gordy

As Ever, Gordy Anna on the Farm

Anna on the Farm The Doll in the Garden

The Doll in the Garden Daphne's Book

Daphne's Book Witch Catcher

Witch Catcher The Gentleman Outlaw and Me--Eli

The Gentleman Outlaw and Me--Eli Wait Till Helen Comes

Wait Till Helen Comes Took

Took A Haunting Collection

A Haunting Collection Anna All Year Round

Anna All Year Round The Girl in the Locked Room

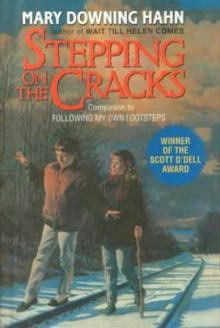

The Girl in the Locked Room Stepping on the Cracks

Stepping on the Cracks