- Home

- Mary Downing Hahn

The Doll in the Garden Page 7

The Doll in the Garden Read online

Page 7

“That white cat,” she said abruptly. “You girls put him in my yard last night, didn’t you? You were trying to scare me.”

“You know who that cat is and where he comes from,” I said. I was feeling pretty brave, but my voice sounded shaky. “He’s here to get Louisa’s doll, and you better give it back before it’s too late!”

Miss Cooper gripped her cane tighter and backed away from me. “It’s already too late,” she said. “Louisa’s been dead since 1912. Nothing can change that.”

She paused a moment, breathing heavily. “If you don’t believe me, go to Cypress Grove Cemetery and see for yourself, missy. Just look for the pink angel her aunt put up for her!”

Kristi looked at me, her eyes full of tears, and I glared at Miss Cooper. “How could you be so mean?” I asked. “Louisa was an orphan, and she was sick. You must have known she was going to die, but you took Anna Maria anyway.”

“You had no business digging that doll up!” Miss Cooper snapped at me.

“And you had no business burying her!”

Miss Cooper looked from me to Kristi, her mouth pursing and unpursing. “I just borrowed the doll,” she said at last and lifted her chin, daring us to contradict her. “I meant to give her back, but that aunt of hers wouldn’t let me in the house. She said Louisa was too sick for company; she said to come back when she was feeling better. I didn’t think Louisa was going to die. What does a child know of death?”

“Why didn’t you just give Anna Maria to Aunt Viola?” I asked.

Miss Cooper turned her head away, her eyes seeking Louisa’s yard. “That woman didn’t like me. Nobody did. I was always in trouble. Do you know what Papa would have done if he’d known I’d taken the doll?”

The old woman stared at me, and I shrugged and looked down at my bare feet. I was starting to feel sorry for her, and I didn’t want to. Not when she’d been so mean to Louisa.

“He’d have beaten me with his belt,” Miss Cooper said, “and then he’d have locked me in the coal cellar and left me there in the dark till he was sure I’d repented.”

“Is that why you buried her?” I asked. “So no one would know you took her?”

Miss Cooper nodded. “When they told me Louisa was dead, it seemed the right thing to do. I sneaked out of the house late at night and buried her under Papa’s best rosebush. I knew nobody would dare dig near its roots.”

She paused a few seconds and then added softly, “I even said the right words, the very ones I heard at Louisa’s funeral.”

Miss Cooper rummaged about in her pocket and pulled out a wrinkled handkerchief. She blew her nose carefully. “Don’t you think I haven’t felt bad about it all these years?” she said. “You’re too young to know, but the things you do when you’re a child stay with you all your life.”

“But you can change it now,” Kristi said. “You can give Anna Maria to Louisa.”

“How can I do that?” Miss Cooper peered at Kristi as if she thought she was crazy. “Louisa’s been dead over seventy years. Time doesn’t run backward, you know, and things that have been done can’t be undone, no matter how hard you wish.”

“But Snowball can take us through the hedge to Louisa’s garden,” I said. “The house is there, and she’s there, and so is Aunt Viola. We’ve seen Louisa and talked to her, that’s how we know how much she wants Anna Maria.”

“Why are you telling me lies?” Miss Cooper’s voice rose and quavered as she leaned toward me. “You are a wicked child.”

“I’m not lying!” I was getting angry. “Just give us Anna Maria so we can take her to Louisa before she dies.”

Kristi began crying. “Don’t you see?” she said to Miss Cooper. “If she gets the doll back, maybe she won’t die. We want to save Louisa’s life.”

I don’t know what would have happened if Snowball hadn’t come walking across the grass at that moment. Miss Cooper saw him first. “Louisa’s cat,” she hissed. “Get him away, get him away!”

Picking Snowball up, I caressed his white fur. “He won’t leave till you give Anna Maria back,” I said. “Won’t you please get her? Please!”

The three of us stood facing each other like children frozen in a game of statues. At last Miss Cooper said, “The world’s full of white cats. They all look just the same.” Her voice was shaking and the hand clutching her cane trembled.

“But they have shadows, right?” While she watched, I set Snowball down on the grass. “All except this one.”

Miss Cooper, Kristi, and I looked at the ground at Snowball’s feet. His fur shone in the sunlight, his pink nose glistened with health, his big green eyes stared up into ours, but no shadow anchored him to the earth. Meowing softly, he took a few steps toward Miss Cooper and she backed away.

“I knew it all along,” the old woman whispered, more to herself than to us. “But I didn’t know what they wanted. I told myself they were just tormenting me because I didn’t go to see her before she died.”

Miss Cooper paused and Snowball rubbed against her legs, purring. She flinched a little, but she didn’t move away. Slowly she bent down and ran a hand lightly over his fur. “You feel so real,” she said.

Then she straightened up and looked at me. “You say it’s the doll. If Louisa gets her back she’ll rest quiet and leave me be?”

I nodded, and the old woman sighed. “All right,” she murmured. “All right.”

Letting out my breath in a long, slow sigh of relief, I watched Miss Cooper hobble around the side of her house and climb her steps. Krisd clutched my arm, and Snowball purred as he watched the house, too, waiting for Miss Cooper to come back with Anna Maria.

Chapter 17

Louisa and Carrie

AFTER WHAT SEEMED like a very long time, Miss Cooper opened her front door and walked slowly toward us. She was carrying Anna Maria as if she were a real baby, and I noticed she’d washed the doll’s face and clothes and curled her hair. Except for the chip on her nose, Anna Maria looked almost as good as new.

When I reached for the doll, though, Miss Cooper shook her head. “No,” she said, “I’m going with you. If there’s any truth in this, I want to see it for myself.”

“But Louisa won’t know who you are,” I said. “She thinks you’re still a little girl.”

Miss Cooper frowned and stuck her Up out as if she were Kristi’s age. “If you want the doll returned, you have to let me do it.”

I could tell by the expression on Kristi’s face that she didn’t want Miss Cooper to come, but to me it made sense. Since she had taken Anna Maria, it seemed right for her to give her back to Louisa.

“Maybe it won’t work if she comes,” Kristi said to me.

“Maybe it won’t work if you come.” Miss Cooper clutched Anna Maria and scowled at Kristi.

While the two of them glared at each other, Snowball brushed against Miss Cooper and meowed. Forgetting everything else, the three of us followed him around the house and across the backyard. As we approached the gap in the hedge, I looked up at our apartment, hoping Mom wouldn’t see us parading across the lawn. She was nowhere in sight, but I could hear the clatter of her typewriter.

“He’s waiting for us.” Kristi tugged at my arm and pulled me toward Snowball. The cat was standing by the hedge. His green eyes were huge as he watched Miss Cooper walk slowly toward him and stop a few feet away.

“Come on,” I took the old woman’s arm and tried to pull her toward Louisa’s yard.

“I’m afraid.” Miss Cooper resisted me. In the hot sunlight, she looked as old and fragile as the doll she held in her arms. “What will happen to me if I go with you?”

Kristi and I looked at each other. “Nothing,” I said, but how did I know?

“What’s Louisa like?” Miss Cooper asked. “Is she a ghost? A spirit?”

“She’s just as real as I am,” I said. “She’s thin and small and her hair is long and golden, the color of honey.”

Miss Cooper’s mouth twitched, but she didn’t say

anything. Lowering her head, she caressed Anna Maria’s curls. “I fixed her up the best I could,” she said, “but I couldn’t do anything about her nose. I hope Louisa won’t be mad about it.” Miss Cooper looked at me. “Do you think she’ll forgive me for treating her so badly?”

From what I knew of Louisa, I was sure she wouldn’t bear anyone a grudge. Gently, I led Miss Cooper toward the hedge, and the three of us followed Snowball into the dusky world on the other side.

…

The first thing I noticed was the darkness. It wasn’t twilight this time but mil night. The moon shone high overhead, and Snowball’s fur shimmered as he ran through patches of shadow toward Louisa’s house. The air was cool against my skin and a breeze made me shiver.

Kristi grabbed me. “She’s gone,” she whispered. “She didn’t come after all.”

“Miss Cooper?” I looked behind me into the dense shadows near the hedge. The leaves stirred and rustled, and, as Kristi and I watched, a little girl appeared. She was shorter than I was, and her long straight hair tumbled around her thin face. In her arms was Anna Maria.

While Kristi and I stood staring, the girl gazed at the house, her eyes scanning the upper story. One light shone from a window. In the silence, I heard her draw in her breath.

Clutching Anna Maria, Carrie Cooper walked right past Kristi and me. Without looking at us, she slowly climbed the back steps and paused at the door where Snowball sat waiting. Cautiously she turned the knob and slipped inside with Kristi and me behind her.

We followed Carrie through an old-fashioned kitchen, down a dark hall, and up a flight of carpeted steps. Scarcely daring to breathe, Kristi and I watched her stop in front of a closed bedroom door. A crack of light shone under it, and Carrie pressed her ear against the wood. Hearing nothing, she opened the door quietly and peered into the room.

Although Kristi and I tried to go with Carrie, Snowball stopped us on the threshold and forced us to stay in the shadows like an audience in a darkened theater watching a play unfold upon a stage.

The room was lit softly by a heavily shaded lamp beside an old oak bed. In a chair next to the bed sat Aunt Viola, fast asleep. In the bed, her head propped up on a lacy pillow, was Louisa. The lamplight gleamed on her hair, turning her curls to gold, but her eyes were closed and deeply shadowed. Her face was ashy white and her thin hands clutched the covers.

While we watched, Carrie approached the bed, holding Anna Maria like an offering. In the light from the lamp, I could see her sharp face and small, pointed chin, her dark eyes, and the frown creasing her forehead.

As Carrie bent over the bed, Louisa opened her eyes. “Carrie,” she whispered. “Is it really you?”

“I brought her back.” Carrie laid Anna Maria in Louisa’s arms. “I just wanted to borrow her for a little while. I didn’t mean to keep her so long.” Carrie ran a finger lightly over the doll’s hair, but her eyes were fixed on Louisa’s pale face.

Louisa smiled. “It’s all right,” she said, hugging the doll. “You knew how much I needed her, so you brought her.”

“I would have come sooner,” Carrie said, “but your aunt wouldn’t let me in the house.” She stole a glance at Aunt Viola who sighed without opening her eyes.

“She tries hard to do what’s best for me,” Louisa said, “but she makes mistakes sometimes.”

“Are you sure you forgive me?” Carrie came closer to Louisa, and I could hear the tears in her voice.

Louisa reached out and grasped Carrie’s hand. “You’re my best friend, Carrie. Nothing can ever change that.”

Holding Anna Maria tightly, Louisa lay back on her pillow and smiled at Carrie. For a moment her eyes sought mine and Kristi’s, but when I tried to approach the bed, Snowball pressed against me, keeping me in the hall.

“Don’t leave me, Louisa,” Carrie said. “Get well, and I’ll be a better friend, you’ll see. I’ll never tease you or take your things. I promise.”

Louisa turned her head and coughed. When she looked at Carrie again, her face was paler. “I’m very tired now,” she whispered. “Perhaps you’d better leave. If Aunt Viola awakes and finds you here, she’ll be cross.”

But Carrie fingered. She smoothed the pillow under Louisa’s head and brushed her curls lightly with one hand. “You have Anna Maria now,” she said. “She’ll make you get well, I know she will.”

But Louisa shook her head. “Soon I’ll be with Mama and Papa. I heard Doctor McCoy tell Aunt Viola when he thought I was sleeping.”

Carrie stared at Louisa, but the little girl’s eyes were already closing. Bending down, she kissed Louisa’s cheek. TU always be your friend, I promise,” Carrie said. “And when you’re well, we’ll have tea parties in the garden again and you can read to me from your fairy tale book.”

Louisa lay still, her eyes closed, a little smile curving her lips. Once more Carrie touched the doll, and then without looking back she ran from the room.

Chapter 18

A Visit to Cypress Grove

THE MOONLIGHT silvered the yard as Snowball led Kristi and me out of the house. When I looked up at Louisa’s bedroom window, I saw Aunt Viola peering out into the garden, but she didn’t notice me. She was looking at the hedge, which was swaying as if someone had run through the gap ahead of us.

“Where’s Carrie?” Kristi asked me. “We can’t leave her here.”

“She must have gone home without us,” I said.

“Let’s go.” Kristi pushed past me, but I lingered a moment, watching Louisa’s window. Aunt Viola was gone, but the light still glowed softly.

“Goodbye, Louisa,” I whispered, knowing as I spoke that I would never see her again. She had sent Snowball to me for the last time, and she was sleeping now with Anna Maria in her arms.

“Come on, Ashley.” Kristi pulled my arm. “It’s scary here in the dark, and I’m cold.”

Ignoring her, I stooped down and stroked Snowball’s fur as he rubbed against my legs and purred. “I won’t see you again either,” I told him.

Tears filled my eyes as he slipped away from me and ran up the steps. Leaping to the sill of an open window, he crawled into the house. I waited and in a few seconds I saw him looking down at me from Louisa’s room. Then he was gone and Kristi was pulling me through the hedge.

…

As we stumbled out of the shrubbery and into the afternoon’s hot sunlight, we almost tripped over Miss Cooper. As old and wrinkled as ever, she was sitting on the grass in her own yard. When she saw Kristi and me, she said, “It was all true what you told me, all true.”

“You gave Anna Maria back to Louisa,” I said, “just like you promised.”

“Yes,” Miss Cooper said, “I did, didn’t I?”

“And she forgave you,” I added.

Miss Cooper smiled then and her wrinkles shifted and reshifted, forming new patterns. “She died peaceful,” she said. “She died my friend.”

Stunned, I watched Miss Cooper struggle to her feet. “She couldn’t have died,” I said. “She couldn’t have.”

Miss Cooper glanced at me and shook her head. “She died on this very day in 1912. I told you that.” Then she hobbled away, leaving Kristi and me standing in the hot sunshine staring after her, too dumbstruck to speak.

“Come on.” I grabbed Kristi’s arm and started running. Despite the heat, we raced across the lawn and down Homewood Avenue toward Lindale Street.

“Where are we going?” Kristi cried.

“To Cypress Grove,” I shouted. “It can’t be true, Louisa can’t be dead, not after all we did.”

By the time we’d run the five blocks to the cemetery, we were panting and soaked with sweat. At the iron gates, I paused a moment, almost afraid to enter the still, green landscape ahead of me.

“You said she wouldn’t die if she got her doll back,” Kristi said. Her voice was so sharp with accusation you’d think I’d deliberately betrayed her.

Ignoring Kristi, I walked slowly down a gravel roadway. Unlike the me

morial park where Daddy was buried with only a brass plate to mark his grave, Cypress Grove was an old cemetery, and you couldn’t mistake it for anything but what it was. Many of the stones had fallen over and lay half-buried in the grass. The inscriptions were hard to make out, partly because the writing was old-fashioned and partly because the words had been almost worn away by years of rain and snow.

“If we don’t find her grave, then she didn’t die,” I told Kristi, but even as I spoke I saw the pink stone angel Miss Cooper had told us about. It was standing in the shade of a holly tree, somberly regarding the ivy curling around its base.

It was a hot, dry July day, and leaves from the holly tree littered the ground! As we stepped into its shade, the leaves crunched under our bare feet, cutting our skin with their sharp edges. Sunlight and shadows mottled the little angel. Slowly I made out the letters carved into the stone:

LOUISA ANN PRKINS

BELOVED DAUGHTER OF ROBERT ALAN PERKINS

AND

ADELAIDE JOHNSON PERKINS

JANUARY 11, 1903 – JULY 17, 1912

MAY SHE REST IN PEACE

WITH THE ANGELS OF THE LORD

“She died. Louisa died,” Kristi whispered.

I grabbed Kristi’s hand and squeezed hard. Louisa was as real to me as Kristi, and my eyes filled with tears as I remembered the way she’d hugged Anna Maria and then fallen asleep. We’d tried so hard, Kristi and I and even Miss Cooper, but we hadn’t kept Louisa from dying any more than Mom and I had kept Daddy from dying.

We’d failed, and the same anger I’d felt at Daddy redirected itself toward Louisa. Just like him, she’d deserted me. I’d never see her again; I’d never see him again. How could they just turn their backs and leave me?

Sinking to the ground beside Louisa’s grave, I cried so hard my chest ached. All my tears for Daddy, the ones I’d held back so long, poured out of me. “How could you do it?” I sobbed. “How could you go?”

Mister Death's Blue-Eyed Girls

Mister Death's Blue-Eyed Girls The Ghost of Crutchfield Hall

The Ghost of Crutchfield Hall Hear the Wind Blow

Hear the Wind Blow Time of the Witch

Time of the Witch The Girl in the Locked Room: A Ghost Story

The Girl in the Locked Room: A Ghost Story All the Lovely Bad Ones

All the Lovely Bad Ones One for Sorrow

One for Sorrow Deep and Dark and Dangerous

Deep and Dark and Dangerous Tallahassee Higgins

Tallahassee Higgins Promises to the Dead

Promises to the Dead Took: A Ghost Story

Took: A Ghost Story Following My Own Footsteps

Following My Own Footsteps Wait Till Helen Comes: A Ghost Story

Wait Till Helen Comes: A Ghost Story Where I Belong

Where I Belong The Spanish Kidnapping Disaster

The Spanish Kidnapping Disaster Look for Me by Moonlight

Look for Me by Moonlight The Old Willis Place

The Old Willis Place Closed for the Season

Closed for the Season As Ever, Gordy

As Ever, Gordy Anna on the Farm

Anna on the Farm The Doll in the Garden

The Doll in the Garden Daphne's Book

Daphne's Book Witch Catcher

Witch Catcher The Gentleman Outlaw and Me--Eli

The Gentleman Outlaw and Me--Eli Wait Till Helen Comes

Wait Till Helen Comes Took

Took A Haunting Collection

A Haunting Collection Anna All Year Round

Anna All Year Round The Girl in the Locked Room

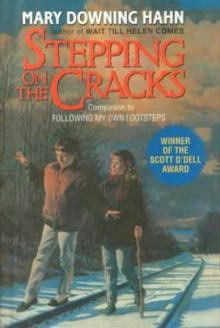

The Girl in the Locked Room Stepping on the Cracks

Stepping on the Cracks