- Home

- Mary Downing Hahn

One for Sorrow Page 7

One for Sorrow Read online

Page 7

“Ninety-eight point six,” he said. “Just right.”

I didn’t have the flu. Not yet.

After dinner, I picked up my old copy of Little Women and turned to the description of Beth’s death. Picturing the possibility of my own death, I began to cry, at first quietly, then louder.

Father looked up from the evening paper in alarm. “What on earth is wrong, Annie? It’s just a book. Nothing to cry over.”

Mother sat on the sofa beside me and stroked my hair. “Something has upset you,” she murmured. “Is it the death of the Schneider girl?”

“How did you know?”

“Her obituary is in the Evening Sun.”

I cuddled closer to Mother, seeking warmth and comfort. “How long are people contagious before they actually get the flu?”

Mother looked at me. “Were you around Elsie before she got sick?”

“We were in the park last week, I can’t remember exactly when, and we were playing. She didn’t seem sick then.”

Father looked at me over the paper. “I believe the incubation period is about three days, so if you saw her a week ago, you’d already have it.”

“What if you touch something the person has, can you catch it that way?

“For example?” Father asked.

“Elsie was wearing a flu mask, and she let Rosie try it on. Lucy and Eunice tried it on, too.”

“Did you and Jane try it on?” Father asked. The concern in his voice scared me.

“No. We were afraid of it. We didn’t even touch it.”

Father and Mother exchanged worried looks. “I’m glad you didn’t put it on,” Mother said.

“Do you think Rosie and Lucy and Eunice will catch the flu?”

“I hope not,” Mother murmured, hugging me close again.

“Perhaps you shouldn’t play with them for a few days,” Father said.

“Horace, for heaven’s sake,” Mother said. “Don’t frighten Annie with talk like that. You just said the incubation period was three days.”

“Usually it’s three days,” Father said glumly, “but with this flu, who can be sure of anything?”

“Should I call the girls’ mothers and advise them to keep an eye on their daughters?”

“Oh, I’m sure they’ll be all right.” Father backtracked hastily, probably so as not to worry me. “They were outside in the fresh air.”

The phone rang and Mother hurried into the hall to answer it. I heard her murmuring but not clearly enough to understand what she was saying. Suppose it was Rosie’s mother calling to say Rosie had died of the flu?

When Mother hung up, I was prickling all over, terrified of what she might say.

“That was Miss Harrison,” Mother said, taking a seat beside me. “Elsie’s funeral will be at the First Lutheran Church tomorrow. She hopes all the girls in her class will attend and sit together. Do you think you can muster the courage to go?”

“Of course she can,” Father said behind his newspaper. “It’s the proper thing to do.”

“But Annie has never seen a dead person,” Mother said. “And she’s so sensitive.”

Ashamed to look at my parents, I slid deeper into the sofa. I’d probably seen more dead people than both of them. Without making much of an effort, I began to cry again.

“Oh, Father, don’t make me go,” I begged. “I don’t want to see Elsie. I can’t bear it.”

Through half-closed eyes, I saw them look at each other, obviously concerned. Mother shook her head, and Father shrugged.

“Of course you don’t have to go,” Mother said softly. “Unlike some parents, I’ve never believed children should be forced to attend funerals. Especially ones with delicate natures like you, Annie.”

Feeling guilty, I went up to bed, but I lay awake a long time, thinking about Elsie’s death and fearing my own. The wind blew around the house, and the windowpanes rattled as if someone were trying to get into my bedroom.

When I finally fell asleep, I dreamed that Elsie was sitting on my bed, watching me. When she leaned over me, her hair brushed my cheek and I felt the touch of her cold hand on my hand. She clasped Antoinette tightly.

“You think you’re rid of me,” she whispered, “but you’re wrong. I’m still here, Annie.” With that, she yanked off Antoinette’s wig. Hundreds of worms slithered out of the hole in the doll’s head.

I woke up screaming so loudly that Mother rushed into my room with Father behind her.

“What is it, Annie?” Mother cried, gathering me into her arms.

“Elsie,” I cried. “Elsie was sitting on my bed, Mother, right where you’re sitting now. She wasn’t dead, she—” I couldn’t go on.

Father patted my shoulder. “There, there, Annie. It was a dream, that’s all. Try not to think about that poor girl.”

Father went back to bed, but Mother sat with me awhile. “Would you like me to sing to you like I did when you were little?”

“Yes, please. Sing the lullaby about the western sea.”

While I clung to her hand, she sang “Sweet and low, sweet and low, wind of the western sea.”

Gradually I relaxed. With Mother beside me, I was safe. No harm could come to me. Elsie was gone. She wouldn’t return. Couldn’t return.

The next morning, church bells woke me up. Not funeral knells but wild ringing as if maniacs were swinging on the ropes. Frightened by the clanging of so many bells, I ran downstairs. Mother and Father grabbed my hands and laughed out loud.

“Don’t look so worried, Annie!” Father said. “They signed the Armistice! The war is over!”

Mother looked at the kitchen clock. “Officially the celebration begins this morning on the eleventh hour, of the eleventh day, of the eleventh month,” she said, “but the treaty was signed at five a.m. in France, and nobody’s waiting until it’s eleven a.m. here.”

She opened the back door, and in came the cold November air, bringing with it the din of the bells. People cheered and fireworks exploded. Mother grabbed pots and lids and handed some to Father and me.

“Come on,” she cried. “Let’s add our part to the celebration.”

We ran out into the street and joined our neighbors. Mr. Elliot from across the street was blowing a trumpet. His son, who played in the high school band, was pounding a drum and our next-door neighbor Mr. Higgins actually had a tuba. They were trying to play “Over There,” and it sounded so horrible it was wonderful.

After the cold chased everyone back into their houses, Mother made hot chocolate, and we raised our mugs and drank a toast to Mother’s brother, Paul, who’d be coming home soon. In celebration, Mother made pancakes and bacon and scrambled eggs. She even let us have slices of cake left over from dinner last night. By the time I finished eating, I thought my stomach would burst wide open.

It wasn’t until I walked over to Jane’s house that I realized I hadn’t thought about Elsie once. Jane saw me coming and ran to meet me. “Let’s go to Prospect Street and watch the parade,” she cried.

Forgetting Elsie again, I ran with Jane toward the sounds of a real marching band playing the National Anthem. Mobs of happy people followed the band, singing and yelling and waving flags. Rosie caught up with us. She had her brother’s police whistle and we took turns blowing it. Lucy and Eunice found us in the crowd, and we let ourselves be carried along, giddy with excitement.

The band turned a corner. They were playing “Alexander’s Ragtime Band,” and people were dancing in the street.

We passed the First Lutheran Church just as the pallbearers brought a coffin down the steps—a coffin too small for an adult. Mr. and Mrs. Schneider followed it, walking slowly, their heads down, their faces pale against their black clothing. Miss Harrison came close behind them, leading a group of our classmates. When she saw us in the crowd of revelers, she frowned.

The parade came to a halt, of course. The band stopped playing and bowed their heads. Men removed their hats and put their hands on their hearts. Women stood silently,

their faces full of grief for their own losses.

Paralyzed with shock at the sight of Elsie’s coffin, all four of us stood there in plain view. Mr. and Mrs. Schneider both saw us. For a moment I was afraid they were going to cross the street and confront us, but they shook their heads and climbed into the carriage behind the hearse.

Even after the funeral procession had vanished, the crowd spoke in low voices. The band marched away silently and didn’t play until they were out of sight.

“Let’s get out of here,” Rosie said, but we weren’t fast enough to escape Miss Harrison.

“I’m shocked to see you celebrating instead of attending Elsie’s funeral.” She looked at us in a way that made us all feel like monsters without consciences. “I truly thought better of you.”

Her eyes moved from one of us to another. “I talked to your parents last night. I told them the time and the date. Everyone, except Annie’s mother, said you’d be at the church with your classmates. Yet here you are, rowdy and rude, behaving like hoydens as if I’d never taught you proper etiquette. You have deeply disappointed me.”

With that, she turned away, head up, back stiff, and joined the well-behaved girls waiting for her.

“Teacher’s pets,” Eunice muttered.

Nobody else had anything to say. We’d lost our enthusiasm for the parade. What was there to do but go home?

Ten

URING THE MONTHS after Elsie’s death, funeral knells still rang, but not five or six times a day as they had earlier. We didn’t see as many hearses in the streets or funeral wreaths on doors. In December, school reopened and the four of us worked hard to win back Miss Harrison’s approval. Besides Elsie, two girls at Pearce died of the flu, but they weren’t in our class, and we didn’t know them.

Uncle Paul came home for Christmas, but he shared no war stories with us. He was pale and thin and walked with a limp. He looked older, too. And he seemed uncertain about things. Even though he’d survived the war, Mother continued to worry about him.

A few days after Christmas, Uncle Paul caught a train to Ohio to live with my grandparents.

We stood on the platform waving until the train was out of sight. As we returned to the car, Mother took Father’s arm. “He’s not himself,” she murmured.

“Perhaps with the passage of time,” Father began, but dropped his voice so low I couldn’t hear what he said next.

I dawdled behind them, knowing they didn’t want me to overhear their worries. I’d seen the change for myself.

In January, the snow began. We went sledding every day after school and all day on weekends. High Street was our favorite. The hill was so steep you felt as if you were flying, but you had to be careful not to crash into the stone wall at the bottom.

A boy named Henry had been killed there last year. He fractured his skull and died instantly. Some kids claimed Henry’s ghost haunted the place where he’d died. They said his ghost tried to make kids crash into the wall, but they just wanted to scare us.

A group of older kids kept a bonfire going at the top, and parents often provided marshmallows and hot chocolate. Best of all, our parents allowed us to stay out after dark as long as we were home by eight. We felt grown-up and daring and ready for adventures.

One night Rosie asked, “Are you getting tired of High Street?”

“Do you know a better place?” Lucy asked.

“Follow me!” Rosie grabbed her sled, did a perfect belly flop, and sped down the hill.

We flew behind her, our sled runners bouncing over the ruts made by other sleds, a cold wind in our faces, swerving around the corner at the bottom of the hill, and coming to a slow stop on Prospect Street.

“Where are we going?” Eunice asked.

Rosie smiled. “You’ll see.”

We turned onto Railroad Avenue, which ran downhill and crossed the train tracks. Ahead of us was the flour mill and the little shanties built for the people who worked there. Behind curtained windows, lamps shone, casting rectangles of light on the snow. Some were vacant, their windows and doors boarded up, snow heaped high around them.

“Where are we going?” Eunice asked again.

Without answering, Rosie turned the corner on Hilton Avenue and hopped on her sled to coast downhill. The rest of us followed her.

At the bottom, Rosie stopped. “Here we are,” she cried. “The steepest hills in Mount Pleasant!”

With a big grin, she pointed to a massive iron gate decorated with metal leaves and fanciful vines. On it was a sign:

FOREST HEIGHTS CEMETERY

HOURS: EIGHT A.M. TO SUNSET

Of all the places Rosie might have chosen, I hadn’t expected the cemetery. It was almost as old as the town itself, which meant the burials went back to the 1700s, and it was built on acres and acres of steep hills. A fence surrounded it, its bars tall and straight, their tops pointed like ancient weapons. To keep the living out or the dead in? I wondered.

The moon lit the graves as bright as day, rows and rows of them climbing the hillsides, everything from stone markers for the poor to columns and statues and rows of mausoleums for the rich. So many dead people, more of them than the entire living population of Mount Pleasant, especially now that the flu had taken its terrible toll.

It was the loneliest sight imaginable, a perfect setting for an Edgar Allan Poe story. Jane reached for my hand. We drew close together.

Trying to sound braver than I was, I said, “It’s just a cemetery, Jane.” Just a cemetery—those tombstones gave me the shivers, but I told myself it was the wind that made me shiver, not the cemetery.

“How are we supposed to get in?” Eunice pointed at a padlock as big as her hand, fastened to the gate with thick chains.

“My brother told me about a place where the bars are bent apart.”

Dragging our sleds behind us, we floundered through deep snow. The farther we walked, the more I hoped someone had mended the gap.

Suddenly Rosie stopped. “Here it is, right where Mike said.”

The four of us helped her dig away some of the snow. Rosie squeezed through the gap first and maneuvered her sled into the cemetery. Although I had a bad feeling about the cemetery and its occupants, I wasn’t about to say I was terrified and run home.

We all followed Rosie through the gap, even Jane, pulling our sleds in after us. Ahead was a steep hill. Tall, thin tombstones climbed upward. At the top was a row of mausoleums, those scary little houses for the dead.

The wind whispered to itself among clumps of firs and cypresses and rattled the branches of tall oak trees. A freight train blew a long warning blast for the Railroad Avenue crossing. Overhead, the moon gazed down at us with its usual sad look.

Talking loudly, Rosie led the way toward the top, stopping now and then to read a tombstone.

“Here lies Uriah Short,” she said. “His life was cut short.”

“It doesn’t say that!” Lucy pushed her aside to see for herself. “Asleep in the Savior’s arms,” she corrected Rosie. “That’s what it says.”

Rosie laughed. “It was a short sleep, though.”

Eunice laughed loud enough for all of us.

At the top of the highest hill, we belly flopped on our sleds and shot down, swerving around tombstones and trees. The moon cast inky, sharp-edged shadows. My sled bounced over the snow’s icy crust, bucking beneath me like a wild horse. Wind slapped my face with biting cold and snatched my breath away. At any moment I might take to the air and fly over Mount Pleasant as if I rode a magic carpet.

Rosie was the first to coast to a stop at the bottom of the hill. She jumped up from her sled and shouted her joy at the moon.

“Admit it,” she cried, “this is the best sledding place in Mount Pleasant, and I found it!”

“Hooray for you,” Eunice shouted.

“For she’s a jolly good fellow,” sang Lucy, “for she’s a jolly good fellow, for she’s a jolly good fellow, which nobody can deny!”

We all sang another chorus so

loudly our voices echoed back from the row of mausoleums above us.

All of us, that is, except Jane. She stood a little apart, brushing snow from her mittens and frowning. “Don’t make so much noise,” she said.

“Why? “Lucy asked. “Are you scared we’ll wake the dead?”

We all laughed except Jane, who said in a low voice, “It’s disrespectful.”

“Oh, don’t be such a scaredy-cat,” Eunice said.

Turning her back on Jane, she dragged her sled up the hill behind Lucy and Rosie. I hurried after them. Jane lingered behind, and I waited for her to catch up.

The tombstones on this side of the hill were newer. And plainer. And closer together. Rosie began reading names and dates. The birth dates varied, but the death years were all the same—1918, 1918, 1918. We were in the part of the cemetery where the flu victims were buried. They stretched out in all directions, uphill, downhill, and sideways.

We stopped in front of a grave guarded by a small angel. A bouquet of roses frozen black and stiff lay in the snow. The wind blew, and the stems stirred. Their thorns made a faint scritch-scratching sound.

Rosie leaned closer to read the epitaph.

AGNES O’NEIL

BELOVED DAUGHTER OF

EDWARD AND HELEN O’NEIL

BORN SEPTEMBER 3, 1900

DIED OCTOBER 5, 1918

AT REST IN THE ARMS OF THE LORD.

The name was familiar, but I didn’t know why until Jane took my arm and whispered, “It’s the girl from our first viewing—remember? The one who sang in the choir.”

I pictured Agnes as she’d been that day, a pretty girl lying in her coffin, her long hair fanned out on a satin pillow under her head. Now she lay at our feet beneath six feet of earth and four feet of icy hard snow, her eyes closed, waiting to rise from the dead. For a moment, I wondered what she looked like now, but quickly chased the image of a skull from my mind. Mustn’t think such things. Bad dreams.

Suddenly fearful, Jane and I backed away, but Rosie ran a mittened hand over the inscription. “Poor Agnes,” she said. “It must be dreadful to lie here all alone in the cold.”

Mister Death's Blue-Eyed Girls

Mister Death's Blue-Eyed Girls The Ghost of Crutchfield Hall

The Ghost of Crutchfield Hall Hear the Wind Blow

Hear the Wind Blow Time of the Witch

Time of the Witch The Girl in the Locked Room: A Ghost Story

The Girl in the Locked Room: A Ghost Story All the Lovely Bad Ones

All the Lovely Bad Ones One for Sorrow

One for Sorrow Deep and Dark and Dangerous

Deep and Dark and Dangerous Tallahassee Higgins

Tallahassee Higgins Promises to the Dead

Promises to the Dead Took: A Ghost Story

Took: A Ghost Story Following My Own Footsteps

Following My Own Footsteps Wait Till Helen Comes: A Ghost Story

Wait Till Helen Comes: A Ghost Story Where I Belong

Where I Belong The Spanish Kidnapping Disaster

The Spanish Kidnapping Disaster Look for Me by Moonlight

Look for Me by Moonlight The Old Willis Place

The Old Willis Place Closed for the Season

Closed for the Season As Ever, Gordy

As Ever, Gordy Anna on the Farm

Anna on the Farm The Doll in the Garden

The Doll in the Garden Daphne's Book

Daphne's Book Witch Catcher

Witch Catcher The Gentleman Outlaw and Me--Eli

The Gentleman Outlaw and Me--Eli Wait Till Helen Comes

Wait Till Helen Comes Took

Took A Haunting Collection

A Haunting Collection Anna All Year Round

Anna All Year Round The Girl in the Locked Room

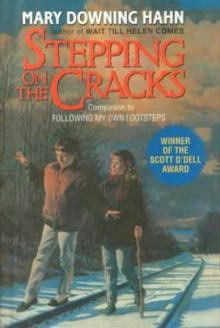

The Girl in the Locked Room Stepping on the Cracks

Stepping on the Cracks