- Home

- Mary Downing Hahn

A Haunting Collection Page 6

A Haunting Collection Read online

Page 6

“Candy Land is a baby’s game,” Sissy told me. “I outgrew it a long time ago.”

“Emma likes it,” I said.

“No, I don’t.” Emma stood in the doorway, frowning as if I’d betrayed her. “I’m way too big to play it.”

“You weren’t too big last night,” I reminded her.

“Well, today I am!” Emma flounced past me and smiled at Sissy. “Do you want to swim or build castles?”

“Both.” Sissy let Emma take her hand. I followed the two of them outside.

At the top of the steps, Sissy looked back at me. “You aren’t invited.”

“Sorry, but Emma doesn’t go anywhere without me,” I said.

“I don’t need you to baby-sit me,” Emma protested. She was learning to scowl exactly like Sissy. The nasty expression didn’t suit her sweet little face. Nor did the sly look she gave Sissy, hoping for her approval.

Sissy ran down the steps ahead of Emma and me and stopped at the bottom, almost as if she was afraid to go farther. “Is your mother in the studio?”

Emma nodded. “She’s painting a big picture of the lake, all dark and scary, like a storm’s coming.” She reached for Sissy’s hand. “Want to see it?”

“Dulcie’d love to meet you,” I added.

Sissy took a quick look through the open door. Dulcie stood with her back to us, hard at work on another painting, darker than the first two. Lake View Three, she was calling this one.

“Hi, Mommy,” Emma called. “We’re going swimming!”

Sissy drew in her breath sharply and ducked away, as if she didn’t want to be seen. Not that it mattered. Without turning around, Dulcie said, “Stay close to shore, Emma. Knee-deep, remember?”

Sissy ran to the end of the dock and posed in a diving position. Her tanned skin contrasted with her faded bathing suit and her pale hair. “Dare me?” she called to Emma.

“Not unless you swim really good,” Emma said uncertainly.

“The water’s over your head,” I added.

“I’ll do it, if you do it,” Sissy said to Emma.

“No.” I grabbed the straps of Emma’s suit. “Emma can’t swim.”

“I can so!” Emma struggled to escape.

I held her tighter. “You’re not allowed to jump off the dock unless your mother’s here.”

“Do you do everything Mommy says?” Sissy asked Emma. “Are you a little goody-goody girl?”

Emma looked confused.

“She has rules,” I told Sissy, “like everyone.”

“Not me,” said Sissy. “I don’t have any rules at all. I do whatever I want.” With that, she jumped off the dock and hit the water with a big splash. She popped back up almost at once, laughing and spluttering. “Emma’s a baby. She sucks her thumb and poops her pants and drinks from a bottle.”

Emma began to cry. “I’m not a baby. I’m almost five years old. I can do whatever I want, too!”

With a sudden twist, Emma broke away from me and ran to the edge of the dock. Before I could stop her, she’d leapt into the lake. One second she was beside me, the next she was gone. I stared at the water in disbelief, too surprised to move.

In a few seconds, Emma’s head emerged, eyes shut, mouth open, gasping for breath. Before she could sink again, I was in the lake beside her, holding her the way the lifeguard had taught me in swimming class.

Emma clung to me but turned her head to shout at Sissy, “See? I’m not a baby!”

Sissy paddled closer. Her hair floated on the water like pale yellow seaweed. “I bet you wouldn’t jump if Ali wasn’t here.”

“I’ll always be here,” I told Sissy. To Emma I said, “If you do that again, I’ll tell your mother.”

“Tattletale, tattletale,” Sissy taunted. “Nobody likes tattle-tales.”

“I’ll jump again if I want,” Emma said, but she made no effort to break away from me. I had a feeling she’d scared herself. The water was deep, and she couldn’t do much more than dog-paddle a few feet.

On the sand, the three of us built castles. Neither Emma nor Sissy said a word to me. They sat close together, their heads almost touching, whispering and giggling.

“It’s rude to whisper,” I told Emma.

Sissy smirked. “So? Nobody invited you to play with us.”

Emma carefully duplicated Sissy’s smirk. “Why don’t you go home? Sissy can be my babysitter.”

“Two’s company, three’s a crowd,” Sissy added. “Don’t you know that yet?”

“If anyone should go home, you should!” I wanted to slap Sissy’s nasty little face, but I knew that would only make things worse.

“Just ignore Ali,” Sissy told Emma. “We don’t like her, and we don’t care what she says or what she does. She’s mean.”

“Meanie,” Emma said. “Ali’s a big fat meanie.”

“Ali’s so mean, Hell wouldn’t want her.” Sissy’s eyes gleamed with malice.

Emma stared at her new friend, shocked, I think, by the word “Hell.” Sissy smiled and bent over her castle, already bigger than the one she’d built yesterday. “It’s not bad to say ‘Hell,’” she told Emma. “It’s in the Bible.”

Emma glanced at me to see what I thought about this. I shook my head, but Sissy pulled Emma close and began whispering in her ear. Emma looked surprised. Then she giggled and whispered something in Sissy’s ear that made her laugh.

I pulled Emma away. “What are you telling her?” I asked Sissy.

“Nothing.” Sissy pressed her hands over her mouth and laughed.

“Nothing.” Emma covered her mouth and laughed, too. She sounded just like Sissy.

I wanted to get up and leave, but I couldn’t abandon Emma. Instead, I moved a few feet away and watched the two of them. Their castles grew bigger and more elaborate. Everything Sissy did to hers, Emma copied. It was pathetic.

“It’s nearly lunchtime,” I told Emma. “Why don’t we go back to the studio and get your mom?”

“Do you want to eat lunch with me?” Emma asked Sissy.

She shook her head. “It’s almost time for me to go home.”

“I thought you didn’t have any rules,” I said. “I thought you could do whatever you want.”

Sissy gave me a long cold look. “Maybe I want to go home.”

“But you don’t have to go,” Emma persisted. “My mommy’s very nice. She fixes good peanut butter and jelly sandwiches.”

Sissy made a face. “I hate peanut butter and jelly sandwiches.”

“I hate them, too,” Emma put in quickly. “Mommy can fix something else for us. Tuna salad, maybe.”

I happened to know Emma despised tuna salad, but I didn’t say anything. What was the use? She probably thought it sounded more grown up than peanut butter and jelly.

“I don’t want to eat at your house.” Sissy looked at me. “Not with Ali there.”

“Maybe we could have a picnic, just you and me,” Emma said. “Outside on the deck.”

“Some other time.” Sissy stood up and looked down at the castles. “They’re pretty enough for a mermaid to live in,” she said. “Do you like mermaids, Em?”

“I saw The Little Mermaid ten, twelve, a dozen times. It’s my favorite movie.”

Sissy tossed her head to get her hair out of her eyes. “Twelve is the same as a dozen, dummy.”

“I’m not a dummy,” Emma said. “I just—”

With a sudden jerk of her foot, Sissy kicked Emma’s castle down.

“You ruined my castle,” Emma wailed. “Now a mermaid can’t live in it.”

“Hey!” With a couple of kicks, I leveled Sissy’s castle. “There! How do you like that?”

“I don’t care.” Sissy laughed. “I can build another one, better than that, and so can Emma. We have all summer to build castles for mermaids.”

She laughed louder. After a moment’s hesitation, Emma joined in. Shouting with laughter, they held hands and spun round and round in circles until they staggered and sprawled on the s

and, still laughing.

I stared at them, slightly worried, maybe even scared of their behavior. “What’s so funny?”

“Everything,” Sissy giggled. “The whole stupid world is funny.”

“Ali’s funny.” Emma laughed shrilly. “Mommy’s funny. You’re funny. I’m funny. The lake’s funny, the seagulls are funny, the—”

Suddenly, Sissy stopped laughing. Her face turned mean. “Shut up!” she shouted at Emma. “You aren’t funny. You’re stupid. And you’re a copycat.”

“I’m not a copycat.” Obviously bewildered by Sissy’s mood change, Emma began to cry.

“Baby, baby copycat,” Sissy chanted, “sat on a tack and ate a rat.” Without looking back, she ran toward the Cove, still chanting.

Emma threw herself against me and pounded me with her fists. “Look what you did! You made Sissy mad! Why can’t you leave us alone?”

I grabbed Emma’s shoulders and held her away from me. Little as she was, her punches hurt. “I didn’t do anything to that brat. She’s a troublemaker, she’s mean to you, she’s—”

“Don’t you talk like that. Sissy’s my friend!”

“Some friend,” I muttered. “Calling you a baby, daring you to jump off the dock, knocking your castle down. Why do you want to be friends with a girl like her?”

“You’re just mad ’cause she likes me, not you.”

“Don’t be silly. I don’t like her. Why should I care that she doesn’t like me?”

“Sissy says you’re jealous—that’s why you don’t like her, that’s why you’re not nice to her. You want me all to yourself!” Emma muttered.

I stared at her, amazed. “How can you believe that?”

“’Cause it’s true!” Emma shouted. “Sissy doesn’t lie!”

With that, she ran away from me. Surprised by the speed of her skinny little legs, I chased her. What would Dulcie think if Emma came home crying?

By the time I caught up with her, it was too late. She’d flung herself into her mother’s arms.

“I hate Ali!” she sobbed. “Make her go home. I don’t want a babysitter!”

Dulcie looked at me, perplexed by Emma’s words. “What’s going on?”

“I’ll tell you later.” Without waiting for my aunt or my cousin, I trudged up the steps toward the cottage.

If Dulcie wanted to send me home, fine. Sissy had turned Emma into a nasty little brat, just like herself, and I was sick of both of them.

10

Dulcie fixed the usual peanut butter and jelly sandwiches and chocolate milk for lunch.

Emma pushed her plate away. “I don’t like peanut butter and jelly,” she whined.

Dulcie looked at her in surprise. “Since when?”

“Since now.” Out went Emma’s lower lip in a classic pout. “They’re for babies.”

“What do you mean? Ali and I eat them. We’re not babies.”

“I want cheese,” Emma said.

“I thought you liked tuna salad,” I said.

Emma glared at me. “I can like whatever I like!”

Dulcie put her hands over mine and Emma’s. “Would you girls please tell me what’s going on?”

“It’s Sissy’s fault,” I told her. “She’s a bad influence on Emma.”

“She is not!” Emma scowled at me.

“Then why was she so nasty to you?” I asked, trying to stay calm.

“She wasn’t,” Emma said. “You were!”

I stared at my cousin, truly shocked. “What did I do?”

Emma turned to her mother tearfully. “Ali called me stupid and said I was a baby.”

“I did not!” I told Dulcie. “I’d never say anything like that. Sissy called her names, not me.”

Emma climbed into her mother’s lap and began to cry. “Ali’s not nice to me and Sissy,” she insisted. “Just ’cause she’s bigger, she thinks she’s the boss.”

Dulcie rocked Emma, but her eyes were on me. I had a sick feeling that my aunt wasn’t sure which one of us to believe. From her mother’s lap, Emma watched me closely, her face almost as mean as Sissy’s.

“It’s not true,” I said weakly. “Sissy—”

“Ali pushed me off the dock, too,” Emma interrupted. “If Sissy hadn’t been there, I would have drowned—”

“That’s a lie and you know it, Emma!” Close to tears I turned to Dulcie. “Sissy dared Emma to jump. I tried to stop her, but she got away from me. She wants to do everything Sissy does.”

Dulcie looked from Emma to me and back to Emma, her eyes worried. “I can’t believe Ali would push you off the dock, Emma.”

“Yes, she would,” Emma insisted. “Ali’s so bad, even Hell doesn’t want her.”

“Emma!” Dulcie stared at her daughter. “Where did you pick up that kind of talk?”

I spoke before Emma had a chance to answer. “Sissy told her cussing was fine. She could say whatever she wanted.”

Dulcie stood Emma on the floor and got to her feet. “I’ve heard enough. Sit down and eat your sandwich.”

“I don’t want any stinky lunch!” Emma started to run out of the kitchen, but Dulcie grabbed her arm and stopped her. “What’s gotten into you?” she asked. “You’ve never acted like this before. Never.”

“I told you,” I said. “It’s Sissy’s fault.”

Dulcie ignored me. This was between her and Emma. “Sit down,” she said. “And eat your lunch.”

Emma took her place between Dulcie and me. She didn’t look at either of us but ate quietly, her head down, her jaws working as she chewed. She left half the sandwich on her plate, despite Dulcie’s pleas to eat it all.

“Do you want me to read a Moffat story?” I asked, hoping to resume our normal relationship.

Emma scowled. “I hate the Moffats. They’re dumb. Just like you!”

“Don’t talk to Ali like that,” Dulcie said. “We never call anyone dumb.”

“Leave me alone,” Emma said. “You’re dumb, too.”

Dulcie frowned. “If this is how you act when Sissy comes here, I don’t want you to play with her anymore.”

Emma responded with a major temper tantrum. She screamed and cried. She told Dulcie she hated her. She threw herself on the floor and kicked.

Finally, Dulcie hauled Emma to her room and put her to bed. Closing the door firmly, she left her to cry herself to sleep.

She dropped back into her chair, her face puzzled. “How can this child have so much influence on Emma so quickly?”

I’d been wondering about this myself. “Maybe it’s because Emma’s never had a friend before. She wants Sissy to like her, so she does everything Sissy tells her to do.”

Dulcie went to the stove and poured herself another cup of coffee. With her back to me, she said, “I guess I really don’t know much about kids. Sometimes I wonder if I was ever actually one myself.”

She laughed, not as if it was funny, more as if it was sad or odd. “I have friends who remember every detail of their childhoods, their teachers’ names, what they wore to someone’s birthday party when they were eight years old, what they got for Christmas when they were ten. Me—I can’t remember a thing before my teen years.”

Dulcie carried her coffee outside. The way she let the screen door slam shut behind her hinted she wasn’t expecting me to follow. She sat at the picnic table, her back to the window, her shoulders hunched. Even without seeing her face, I knew she was unhappy. Maybe her summer wasn’t going any better than mine. Who could have imagined a kid like Sissy would turn up and spoil everything?

I stretched out on the sofa with To Kill a Mockingbird. I was on the seventh chapter with many more to go.

While I read, I heard a car approaching the cottage. I sat up and looked out the window. For some reason I expected to see Mom and Dad, but a big red Jeep emerged from the woods. Dulcie walked toward it hesitantly, apparently unsure who it was.

“Dulcie, it is you!” A plump woman with short silvery blond hair jumped out of the Jeep and sto

od there grinning as Dulcie approached. Her tailored shorts and pink polo shirt contrasted sharply with my aunt’s black T-shirt and paint-spattered jeans.

She stopped just short of giving Dulcie a hug. “Look at you,” she exclaimed, “you’re just as skinny as ever!”

“I’m sorry,” Dulcie said, smoothing her mop of uncombed curls back from her face, “but I don’t remember—”

“Well, no wonder. I wasn’t this fat when we were kids!” She laughed. “I’m Jeanine Reynolds—Donaldson now. We used to play together when you and Claire came to the lake.”

“Jeanine,” Dulcie repeated. “Jeanine. . . . I’m afraid I—”

“Oh, don’t worry about it. Good grief, it’s been what? Thirty years, I guess.”

“My sister would probably remember you.”

“Is Claire here, too?”

“No, but her daughter, Ali, is staying with us this summer.”

Jeanine nodded and looked at the cottage. “It’s just the same as I remember. I hear you had Joe Russell working on it. He’s good. Not cheap, though.”

“Compared to New York, he’s a bargain,” Dulcie said.

Jeanine sat down at the picnic table. “Is that where you live?”

Dulcie nodded. “Would you like something to drink? I’ve got mint tea in the fridge, if you’d like that.”

“Anything, as long as it’s cold,” Jeanine said. “Today’s a real scorcher.”

Leaving the woman on the deck, Dulcie came inside. By then I was in the kitchen, ready to help with cheese and crackers if she wanted them.

Dulcie rolled her eyes. “There goes the afternoon,” she whispered.

A few minutes later, I was setting down a tray with an assortment of crackers, cheese, and sliced fruit. Dulcie poured glasses of iced tea for herself and Jeanine and offered me a can of soda. The three of us settled ourselves comfortably under the patio umbrella.

“My daughter, Erin, tells me you’re an artist,” Jeanine said. “I’m not surprised. When we were kids, you were always drawing. You carried a sketchbook and pencils everywhere we went.”

Mister Death's Blue-Eyed Girls

Mister Death's Blue-Eyed Girls The Ghost of Crutchfield Hall

The Ghost of Crutchfield Hall Hear the Wind Blow

Hear the Wind Blow Time of the Witch

Time of the Witch The Girl in the Locked Room: A Ghost Story

The Girl in the Locked Room: A Ghost Story All the Lovely Bad Ones

All the Lovely Bad Ones One for Sorrow

One for Sorrow Deep and Dark and Dangerous

Deep and Dark and Dangerous Tallahassee Higgins

Tallahassee Higgins Promises to the Dead

Promises to the Dead Took: A Ghost Story

Took: A Ghost Story Following My Own Footsteps

Following My Own Footsteps Wait Till Helen Comes: A Ghost Story

Wait Till Helen Comes: A Ghost Story Where I Belong

Where I Belong The Spanish Kidnapping Disaster

The Spanish Kidnapping Disaster Look for Me by Moonlight

Look for Me by Moonlight The Old Willis Place

The Old Willis Place Closed for the Season

Closed for the Season As Ever, Gordy

As Ever, Gordy Anna on the Farm

Anna on the Farm The Doll in the Garden

The Doll in the Garden Daphne's Book

Daphne's Book Witch Catcher

Witch Catcher The Gentleman Outlaw and Me--Eli

The Gentleman Outlaw and Me--Eli Wait Till Helen Comes

Wait Till Helen Comes Took

Took A Haunting Collection

A Haunting Collection Anna All Year Round

Anna All Year Round The Girl in the Locked Room

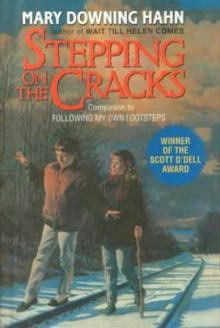

The Girl in the Locked Room Stepping on the Cracks

Stepping on the Cracks