- Home

- Mary Downing Hahn

Anna All Year Round Page 6

Anna All Year Round Read online

Page 6

"There's a burglar upstairs," Mother sobs. "He's hiding under the bed."

"There's a burglar under the bed?" Father looks puzzled.

"He came through the back bedroom window," Anna says. "Great Aunt Emma thought she'd chased him away, but Mother says he's hiding under the bed so he can kill us while we're sleeping."

Aunt Emma raises the poker over her head. "I suggest we go up there, Ira, and teach the scoundrel a lesson or two!"

Father follows Aunt Emma to the foot of the steps and takes the poker.

Mother clings to Father. "Don't go up there, Ira. Call the police!"

Father is even braver than Great Aunt Emma. Telling Mother not to worry, he goes upstairs. Anna, Mother, and Aunt Emma cower in the hall. They hear him walk into the back bedroom. Suddenly he begins to laugh. From the top of the steps, he looks down at them.

"Come up here," he says. "I want to show you something."

"I don't care to see a burglar," Mother says, pressing her hands to her chest.

"There's no burglar, Lizzie," Father says.

"I told you I chased him away," Aunt Emma says proudly.

Anna is the only one who runs upstairs to Father's side. He takes her into the back bedroom. "Do you see what I see?" he asks.

Anna stares at the window. She expects to see broken glass or a rag from the burglar's clothing caught on a splinter of wood. She sees nothing out of the ordinary.

Father points at the window shade. Unlike the shade in the other window, it's rolled up tight.

"Listen closely and tell me if this is what you heard." Father pulls down the shade and lets it go. It flies to the top of the window with a loud bang and wraps itself tightly around the roller.

Downstairs Mother screams and Aunt Emma calls, "Give the scalawag what for, Ira!"

Anna giggles. Father is not only brave, he's smart, too. Holding his hand, she leaves the back bedroom. Together she and Father tell Mother and Aunt Emma about the window shade. In a way, Anna is disappointed it wasn't a real burglar. She would have liked to help Father give him what for.

Summer

10. The Trolley Ride

ONE WARM EVENING IN MAY, FATHER ASKS ANNA IF she'd like to meet him in the city for lunch on Saturday. "You can ride the trolley right to the doorstep of the Baltimore Sun Building," he tells her.

"All by myself?" Anna asks. She's afraid to look at Mother. Surely she'll say no. Anna is only nine, much too young to ride the trolley to Charles Street.

But Mother surprises her. "You can ride on Uncle Nick's trolley," she says. "Number 573. It stops at the corner at 10:43 on the dot. Nick will look after you."

Uncle Nick is a conductor on the trolley. Anna knows he'll make sure she gets off at the right stop.

On Saturday morning, Mother walks Anna to the trolley stop. Charlie tags along. He wishes he could go with Anna, but he's not invited.

"Maybe Father will ask you to lunch with us someday," Anna tells Charlie, but, as much as she likes Charlie, she's glad she's going alone. She doesn't want to share Father with anybody today, not even Charlie. She wants Father all to herself.

Anna, Mother, and Charlie wait on the platform with many other people. Anna wonders where they are all going. The women might be planning to shop in the big stores on Charles Street. The men might be heading for work. Anna is sure she's the luckiest one there. No one else is going to have lunch with Father. Just Anna.

At last Trolley Number 573 comes into sight. It's a summer car. The sides are open and the passengers sit on wooden benches. The motorman stands in front, his hands on the controls. Uncle Nick stands on the running board. He looks handsome in his navy blue uniform and cap.

Anna waits for the passengers to get off. The men and children jump down from the running board, but the ladies back out cautiously. They have to be careful; their long, narrow skirts get in the way.

Uncle Nick touches the visor of his cap and winks at Mother. "Welcome aboard, Anna," he says.

"Take good care of my little girl," Mother says, finally letting go of Anna's hand.

"Indeed I will." Turning to Anna, Uncle Nick says, "Sit right here on the end of the bench where I can keep an eye on you."

When all the passengers are seated, Uncle Nick pulls the bell cord twice to signal the motorman. The motorman rings his bell twice to tell Uncle Nick he's heard. Off the trolley goes.

Anna watches Uncle Nick move up and down the running board, collecting money. She thinks Uncle Nick must be very rich but, when she asks him about the coins filling the change purse on his belt, he tells her it isn't his money. It belongs to the trolley company. "They pay me a salary," he explains. "Believe me, Anna, I earn every cent of it."

The trolley bounces and sways past row after row of red-brick houses with marble steps as white as Mother's. Anna stares at the houses. It's strange to think so many mothers and fathers, grandmothers and grandfathers, children and babies, live their lives just as Anna lives hers. They are all

right here in Baltimore, yet she doesn't know any of them.

She sees a lady older than Great Aunt Emma Moree making her way slowly along the sidewalk. She sees a boy with hair as red as Charlie's. She sees a girl with curls as long and blond as Rosa's. If Anna lived here, would they be her friends instead of Charlie and Rosa?

The trolley heads down Charles Street, deep into the heart of the city. People get off and on at every stop. Now and then a man or a boy jumps off the moving trolley between stops. Others jump on, catching the grab poles with their hands and swinging onboard.

The street is crowded with all sorts of vehicles. Horses pull delivery carts, hauling meat, vegetables, milk, and ice. Motorcars weave in and out, blowing their horns—ooga, ooga! Anna catches a glimpse of a big touring car like the one Uncle Henry drives for his boss. A motorbus squeezes past a large wagon. The horse pulling the wagon rolls its eyes and neighs.

The trolley wheels shriek as they round a corner. The bell rings twice and twice again. Summer air rushes against Anna's face, cool and fresh, bringing smells from the market stalls lining Lexington Street. The sun warms her. If she weren't so eager to see Father, she could ride the trolley all day.

Suddenly Uncle Nick taps Anna's shoulder. "The next stop is Sun Square," he says. "Your father will be waiting there for you."

Sure enough, as the trolley slows down, Anna sees Father on the platform, waving to her.

Uncle Nick holds her hand while Anna jumps off the running board. She waves good-bye and runs to meet Father.

"Well, well," Father says, giving Anna a kiss. "Here's my grown-up daughter, looking very pretty. Did you enjoy your journey?"

"Oh, yes, yes!" Anna hugs Father tight. "But getting here is the best of all!"

Father holds Anna's hand while they cross the street. He shows her the Sun building, where he works, and introduces her to the other reporters. The newspaper office is bigger than Anna imagined. And much noisier. It smells like cigar smoke. She's glad they don't stay there long.

Father and Anna eat at Miller Brothers, the best restaurant in the city, Father says, and one of the oldest. "Even the Baltimore fire couldn't burn it down," he tells Anna.

Just inside the door, Anna stands still and stares around her. Caged canaries sing. Brightly colored fish swim in big aquariums. The tables are covered with white cloths, ironed and starched as stiff as Mother's linen. Each table has its own little lamp with a pink shade. The waiters wear white jackets with two rows of gold buttons. They carry their trays high above their heads, balanced on their fingertips. They never drop anything—not a plate, not a glass, not even a spoon.

After they're seated, the waiter gives Anna her own menu. She studies it carefully, reading each item—appetizers, soups and salads, entrées, desserts, beverages. She feels very grown-up.

"What would you like?" Father asks. "You may have anything your heart desires."

Anna frowns at the menu. It's hard to make up her mind. Should she try something she's never had? Or sh

ould she stick with familiar food?

"What are you having?" she asks Father.

Father glances at the menu. "Perhaps I'll try the escargot," he says.

Anna stares at the word escargot. She would have pronounced it the way it's spelled, but Father has left off the "t."

"Is that a German word, Father?"

"No. It's French."

"What does it mean?"

Father smiles. "Snail."

"Snail?" Anna cannot believe she's heard him properly. "You want to eat a snail?"

Father says, "Yes, I like snails. The chef cooks them in white wine and butter with a pinch of herbs. They're served in their shells."

Anna makes a face. She can't believe Father is serious. She's seen snails on the sidewalk. Nothing could make her eat one.

"Would you like to try a snail?" Father asks.

Anna shakes her head so hard the ribbon almost slides out of her hair. "If you eat one, I'll throw up," she says.

Father laughs again. "Maybe I'll have a nice hot bowl of terrapin soup instead."

Anna knows what terrapins are. She stares at Father. "Turtle soup is almost as bad as snails!"

"How about a crab cake?" Father asks. "Will Princess Anna please allow me to eat that?"

Anna nods. "Yes, Father. You may eat a crab cake."

"Thank you," Father says. "But how about you? What will you eat?"

"A ham sandwich," Anna says, deciding to choose something safe. "And vanilla ice cream for dessert."

After lunch, Father walks back to the trolley stop with Anna. He only works half a day on Saturday, so they ride home together on Uncle Nick's car.

As the trolley bounces along the tracks, Anna rests her head on Father's shoulder and watches the crowded streets and sidewalks pass by. So many people going places and doing things. And today she, Anna, has been one of them. She hopes she can have lunch with Father every Saturday. Maybe next time she'll dare to eat a crab cake. But never a snail.

11. Ladyfingers

IT'S JULY IN THE CITY—TOO HOT TO ROLLER-SKATE, too hot to jump rope, too hot to play hopscotch. Leaves droop. Flowers hang their heads. The street venders' ponies walk slower and slower.

All day long, the sun beats down on the rooftops, streets, and sidewalks. The city traps the heat and holds it tight all night long. No one can sleep. Children stay up late. Grownups sit out front on their marble steps and fan themselves with the evening paper.

One night Aunt May and Mother are sitting side-by-side on the steps, exchanging secrets in German, while Father and Uncle Henry talk about baseball. Anna sits still and listens quietly to her mother and aunt.

"Nein, Nein, Lizzie. Henrietta ist rundlich," Aunt May says, "nicht fett."

Like Father, Anna has picked up a German word here and a German word there, just enough to know Aunt May has said that Aunt Henrietta is plump, not fat. At last Anna is beginning to learn the language of secrets!

Before Mother can reply, Anna says quickly, "Nein, Tante May. Tante Henrietta ist fett, sehr fett!" She puffs up her cheeks and stretches out her arms to show how fat Aunt Henrietta is.

Mother is so surprised she almost falls off the steps, but Aunt May bursts into laughter. "Anna, Anna," she exclaims. "Have you learned German after all?"

Anna looks at Father and giggles. He and Uncle Henry laugh too, but Mother neither smiles nor frowns. It seems she does not know what to think of Anna.

"Ach, Lizzie," Aunt May laments, "what do you expect? Anna ist ein kluges Mädchen. You've told me so yourself."

Winking at Mother, Aunt May begins to talk to Anna in German. She speaks so fast the words run together, long words, hard words. To Anna's dismay, she cannot understand a thing her aunt says.

Aunt May kisses Anna and smiles at Mother. "There, you see, Lizzie? Our secrets are still safe—for now, that is. But with such a clever girl in the house, we must be careful what we say, or Anna will learn all our secrets."

Mother shakes her head and sighs, but Father chuckles. Turning to Anna, he says, "Do you smell what I smell, Anna?"

Anna breathes in the sweet aroma of fresh-baked pastry drifting up the hill from Leidig's bakery. "Ladyfingers," she says. "I can almost taste them."

Father takes Anna's hand. "Come, let's walk down to the corner and treat ourselves."

"Bring something back for Lizzie and me, Ira," Aunt May calls. "Bitte?"

"Don't forget me," Uncle Henry shouts from the doorway.

Anna skips ahead of Father and arrives at the bakery long before he does.

"Well, well, Anna, mein Liebling," Mr. Leidig says. "What will you have this evening?"

Anna closes her eyes for a moment and breathes in the sugar-sweet smell of the bakery. Then she opens her eyes and studies the pretty pink and yellow icing on the cookies, the brown sugar melting on the strudel, the cinnamon swirling on the apple dumplings, the chocolate oozing out of the éclairs, the custard bursting out of the ladyfingers. How can Anna choose? She wishes she could have two or three of everything.

But if she ate that much, she'd soon be as fat as Mr. Leidig. Father says it's a baker's duty to taste all his cakes and cookies to make sure they taste good. It must be true because Mr. Leidig looks like a gigantic gingerbread man, his round face frosted pink, his eyes little dots no bigger than raisins, his hair as white as spun sugar.

When Father arrives, Anna picks a ladyfinger. Father orders half a dozen. Anna watches Mr. Leidig put the ladyfingers in a white box and tie it shut with string. In her head she's counting—one for Father, one for Mother, one for Aunt May, one for Uncle Henry, and one for Anna. That's five. Who is number six for?

"You bought one too many," Anna tells Father.

"My goodness." Father stops at the bakery door. "Shall I return it to Mr. Leidig and ask for a refund?"

"No, no," Anna says hastily. "I'm sure someone will eat it."

"Who do you think that will be?" Father asks.

Anna seizes Father's hand. "Maybe it will be me?"

Father laughs. "That's just who I bought it for."

While Anna watches, Father opens the box and hands her a ladyfinger. "This will give you the energy to climb back up the hill to our house," he says.

When they are halfway home, Anna and Father meet the lamplighter coming slowly down the street. He lights one gas lamp after another, leaving behind him a trail of shining glass globes.

Father and Anna pause to watch the old man light the lamp on the corner. "Soon Baltimore will be electrified," Father says, "and the streetlights will come on all by themselves."

Anna smiles. She thinks Father is joking.

"Mark my word, Anna," Father says. "By the time you're my age, the world will be very different."

Anna realizes Father is serious. He works for the newspaper, so she guesses he knows more than most people about everything. "Will the world be better?" she asks.

"It will be different," Father repeats. "Some things will be better, others will be worse."

"Which will be better?" Anna asks, clinging to his hand. "Which will be worse?"

Father shakes his head. "I don't know, Anna."

Anna holds Father's hand tighter. She cannot imagine anything changing. It frightens her to think of streetlights coming on by themselves. What will the old man do if he has no lamps to light?

"There will be more motorcars," Father says. "And fewer horses."

Even though Anna loves riding in Uncle Henry's boss's big limousine, she isn't ready to give up horses.

"Why can't we have both motorcars and horses?" she asks Father.

He pats her hand. "The world isn't big enough for both," he says softly. "Automobiles go faster than horses. They are new and shiny. People like your uncle want them."

"If I had to choose, I'd pick a horse," Anna says. "You can't be friends with a motorcar."

Father laughs. "Have another ladyfinger, Anna. And then wipe your mouth. Mother doesn't like to see you with a dirty face."

By the time Anna co

mes home, she has eaten her second ladyfinger and cleaned her face with Father's handkerchief. She watches Mother and Aunt May divide up the four remaining ladyfingers.

"Why, Anna," Aunt May says. "Where is your ladyfinger?"

Anna pats her tummy. "I ate mine coming home."

"Oh, Ira," Mother says. "For shame. Only common girls eat in the street. Anna must learn her manners if she expects to get along in this world."

Luckily for Anna, Charlie chooses that moment to call her. Before Mother can say more, Anna runs across the street to play tag with her friends. It's dark now. Charlie, Rosa, Beatrice, Patrick, Wally, and Anna chase each other in and out of the shadows cast by the gas lamps. They play until their parents call them home, one by one.

When everyone is gone but Charlie, Anna tells him what Father told her. Charlie thinks it will be exciting to live in a world where streetlights come on like magic and the roads are crowded with motorcars.

"Do you know what I hope?" Anna asks him.

"What?"

"I hope manners go out of fashion," Anna says.

"No manners." Charlie laughs. "What a wonderful world that would be, Anna!"

Anna smiles. She likes to make Charlie laugh. Maybe she should have given the extra ladyfinger to him instead of eating it herself. Next time Father takes her to the bakery, that's what she'll do.

She tips her head back and gazes at the sky. The stars aren't as bright as they are on winter nights. The hot summer air hangs between the city and the sky, blurring everything, even the moon and the stars. Der Mond und die Sterne, as Mother might say.

Across the street, Aunt May laughs. Fritzi barks. In Charlie's house, a baby cries. Madame Wehman plays her piano. Down on North Avenue, a streetcar bell clangs.

No matter what Father says, Anna cannot imagine anything being different from the way it is right now. It's true that when school starts, Anna will be in fourth grade and her teacher will be Miss Osborne, not Miss Levine. But Charlie will still live across the street, the lamplighter will come every night, Mr. Leidig will bake his ladyfingers, and bit by bit, word by word, Anna will learn Mother's German secrets. As Aunt May says, Anna ist ein kluges Mädchen—a clever girl.

Mister Death's Blue-Eyed Girls

Mister Death's Blue-Eyed Girls The Ghost of Crutchfield Hall

The Ghost of Crutchfield Hall Hear the Wind Blow

Hear the Wind Blow Time of the Witch

Time of the Witch The Girl in the Locked Room: A Ghost Story

The Girl in the Locked Room: A Ghost Story All the Lovely Bad Ones

All the Lovely Bad Ones One for Sorrow

One for Sorrow Deep and Dark and Dangerous

Deep and Dark and Dangerous Tallahassee Higgins

Tallahassee Higgins Promises to the Dead

Promises to the Dead Took: A Ghost Story

Took: A Ghost Story Following My Own Footsteps

Following My Own Footsteps Wait Till Helen Comes: A Ghost Story

Wait Till Helen Comes: A Ghost Story Where I Belong

Where I Belong The Spanish Kidnapping Disaster

The Spanish Kidnapping Disaster Look for Me by Moonlight

Look for Me by Moonlight The Old Willis Place

The Old Willis Place Closed for the Season

Closed for the Season As Ever, Gordy

As Ever, Gordy Anna on the Farm

Anna on the Farm The Doll in the Garden

The Doll in the Garden Daphne's Book

Daphne's Book Witch Catcher

Witch Catcher The Gentleman Outlaw and Me--Eli

The Gentleman Outlaw and Me--Eli Wait Till Helen Comes

Wait Till Helen Comes Took

Took A Haunting Collection

A Haunting Collection Anna All Year Round

Anna All Year Round The Girl in the Locked Room

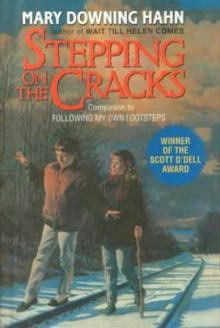

The Girl in the Locked Room Stepping on the Cracks

Stepping on the Cracks