- Home

- Mary Downing Hahn

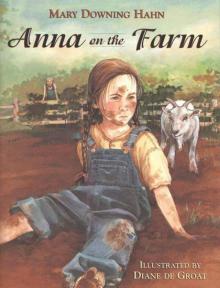

Anna on the Farm Page 4

Anna on the Farm Read online

Page 4

While Anna stands there staring at herself, she feels a breeze on the back of her neck. She shakes her head and watches her braids fly out like long brown ropes. No more thick hot hair hanging down her back, no more ribbons to lose, no more tangles. Anna feels cooler already.

She studies herself in the mirror again, turning this way and that to admire her braids. They aren't blond and the ends don't curl, but Anna likes the way they feel. When she goes back to Baltimore, she plans to wear her hair in braids every day except Sunday. Even if she has to learn to do it herself. Even if her face is long and narrow. Even if her ears stick out. Even if Mother thinks she looks ugly.

Turning away from the mirror, she hugs her aunt, who is just as pale and thin as she is.

"Now, go get ready to take a swim," Aunt Aggie says.

SEVEN

Mud Monsters

ANNA GOES BACK TO HER ROOM AND PULLS A union suit out of the bureau. Although she hadn't wanted to bring it, Anna is glad Mother insisted she'd need it if the weather turned cold. Except for the buttons up the front and the flap in the back, the union suit looks very much like a bathing costume. Maybe Theodore won't notice it's really her underwear.

Anna runs outside, feeling very daring. If Mother saw her, she'd send her to her room for the rest of her life. She'd tell Aunt May that Anna was a disgrace. But Aunt May would just laugh. That would make Mother so cross she'd go home in a huff and refuse to speak to her sister for a week.

Theodore is already in the pond when Anna arrives. She walks out to the end of the little wooden dock Uncle George built and watches him. He's floating on his back with his eyes closed. If he weren't an orphan, Anna would sneak up on him and duck him. But she's promised Aunt Aggie to be nice.

Anna sits down on the end of the dock and dangles her feet in the water. It feels cool. She wants to jump in before Theodore sees her underwear, but she's just a little bit afraid of the pond. Suppose the bottom is muddy? Suppose there are fish that bite? Suppose there are snakes?

Anna glances behind her. Aunt Aggie is sitting on the porch, keeping an eye on the children. Maybe she should go and ask her aunt about mud and fish and snakes and other dangerous things she hasn't even thought of.

At that moment, Theodore opens his eyes and sees Anna. He starts to laugh. "I see Paris, I see France," he calls, "I see someone's underpants!"

Anna feels her face turn bright red. She wants to turn around and run to her room and never come out, but instead she yells, "This is my bathing costume, you big dummy! In Baltimore, it's the latest style!"

Theodore hoots. "I know underwear when I see it!"

Anna is so mad she forgets about the mud and the fish that bite and the snakes. Planning to splash Theodore, she flings herself into the water and sinks into the mud on the bottom.

Anna comes up spluttering. "Oooooh," she screams. "Oooooh!" The mud is slimy and it feels horrible. She slogs toward the shore, screeching, and Theodore chases her, splashing water all over her.

Anna turns around to splash him and gets a face full of water. Without thinking, she bends down and scoops up two handfuls of black gooey mud. She throws them both at Theodore, hitting him right in the face.

He throws mud at Anna. She throws more mud at him. The mud flies back and forth.

"Stop it, Theodore!" Aunt Aggie cries from the dock. "Stop it, Anna!"

The two of them stop and stare at each other. They are both streaked and smeared with mud. It coats their skin and cakes their hair. Anna has never been so dirty in her whole entire life.

Safe and dry on the dock, Aunt Aggie begins to laugh. "All you two need is feathers," she says. "You've already been tarred!"

Theodore looks at Anna. He laughs, too. "You should see yourself," he says. "Your own mother wouldn't know you!"

Anna can't help giggling. Mother would be horrified but not so horrified she wouldn't recognize Anna. Running past Theodore, Anna throws herself face down in the pond and flops around like a fish, swishing herself clean.

When she stands up, she sees Theodore rubbing more mud into his hair. Waving his arms, he prances through the water, roaring, "Look at me, Aunt Aggie! I'm a monster!"

Anna scoops up handfuls of mud. Like Theodore, she rubs it all over herself. "I'm a monster, too!" she shouts. "Look at me, Aunt Aggie! Look!"

Anna throws back her head and howls. She waves her arms. She jumps up and down. She chases Theodore. She ducks him. He ducks her. They splutter and laugh and choke on the pond water.

Aunt Aggie calls Uncle George to come and watch. They stand together on the dock and laugh at the monsters.

Anna can't remember ever having so much fun.

By the time the two of them leave the pond, Anna decides Theodore isn't as awful as she thought. When she glances at him, he grins and tugs one of her braids, but not hard enough to hurt.

"You aren't half bad for a girl," he says and runs off.

Pleased, Anna saunters into the house. Her wet braids thwack her back as she runs upstairs to wash the last of the mud away. Just as she finishes drying her face, she hears Theodore howling in protest. Anna pokes her head out the bedroom window. In the yard below, Uncle George is scrubbing Theodore under the pump.

Anna laughs to herself and pulls on her overalls. A good scrubbing certainly won't hurt Theodore.

After supper, Theodore and Anna sit on the porch steps. It's a hazy night, still hot after the long sunny day. The honeysuckle on the fence glitters with fireflies, but Anna and Theodore are too lazy to catch them.

Behind them, Aunt Aggie and Uncle George talk softly. Their rocking chairs squeak. Jacko scratches fleas. His leg thumps the porch. Somewhere in the dark, a mockingbird sings. Crickets chirp.

"It's so quiet here," Anna says softly.

Theodore nods. "I guess there's a lot of racket in Baltimore. Cars, trains, trolleys. It's a wonder folks can sleep at night."

"You get used to it," Anna says, suddenly feeling homesick for city sounds.

"Not me," Theodore says. "I'm going to be a farmer all my life, just like Uncle George."

"I intend to travel and see the world," Anna says. "The pyramids in Egypt, the Roman Coliseum, the Leaning Tower of Pisa, the Eiffel Tower, Buckingham Palace." As she names the places she plans to see, Anna pictures them as they appeared in her world geography book, drawn carefully in black ink. Someday she'll see them in full color.

"You better marry a millionaire," Theodore says.

Anna sighs. She doesn't know any millionaires and has no idea how she'd ever meet one.

"I'm saving the money myself," she says. "Every time someone gives me a dime or a nickel, I put it in a special jar. When I'm grown up, I'll have at least a hundred dollars."

"If I had a hundred dollars, I'd buy a farm," Theodore says.

Anna gazes at the moon just swinging up from behind the trees. She thinks of Father and Mother sitting on the steps on Warwick Avenue, looking at the same moon she's looking at. If she goes to Egypt or Rome, Paris or London, the moon will be there, too. It will shine down on her in foreign lands and on Father and Mother in Baltimore and on Theodore in Beltsville. Even though they will be far apart, the moon will keep them together.

EIGHT

Cousin Herman

NEXT MORNING, AUNT AGGIE FINDS CHORES FOR Anna to do inside while Theodore works outside. First Anna washes the breakfast dishes, and then she helps her aunt make peach preserves. It's a hot job, but Aunt Aggie promises Anna she will give her three jars to take home with her.

"Each time you spread peach preserves on your breakfast toast, you'll remember your week on the farm," Aunt Aggie says.

When all the peaches are sealed up in Mason jars with tight lids, Aunt Aggie tells Anna she needs a few things from Mr. Buell's Store—a pound of sugar, a half pound of coffee, a pound of flour, and six lemons. She gives Anna a list and two dollars.

"Take Theodore with you," Aunt Aggie says. "There should be enough left over to treat yourselves to peppermint sticks or licorice."

Anna slips the money into her overall pocket and runs outside to find Theodore. He has just finished weeding the garden.

"Aunt Aggie wants us to go to the store," Anna tells him. "We can get candy with the change."

Theodore grins and throws down the hoe. The two of them set off down the lane to the road.

After a few minutes, Anna gets a funny idea. She takes off her hat. Holding her braids on top of her head, she puts the hat back on. "Let's play a trick on Mr. Buell," she tells Theodore. "Let's pretend I'm a boy."

Theodore studies Anna. "He'll never believe that," he says. "You walk like a girl."

"Show me how you walk," Anna says. "And I'll copy you."

Theodore swaggers down the dusty road ahead of Anna, his hands in his pockets. Anna watches him carefully. Shoving her hands in her pockets, she strides after him, taking big steps and bouncing along on her bare feet in a way that would scandalize Mother. By the time they reach Mr. Buell's Store, Anna is sure she's walking just like a boy. Why, she'd probably fool her own father and mother.

Theodore stops on the store's front steps. "What am I supposed to call you?" he asks Anna.

"Herman," Anna says, thinking of one of her German cousins. "Tell Mr. Buell my name is Herman and I'm Aunt Aggie's nephew from Germany."

"Mr. Buell knows your aunt's got no kin in Germany," Theodore says.

"Say I'm a long-lost relative," Anna says, warming to her story. "Say my father is Aunt Aggie's cousin once or twice removed. He went off to Germany and married a duchess, and Aunt Aggie never knew what became of him till now."

"That's plain silly." Theodore spits in the dirt, just missing Anna's big toe. "Mr. Buell will never believe it."

"Just tell him, Theodore!" Anna feels cross. "Don't you have any imagination?"

Theodore shrugs. "Oh, all right. Being from Germany might explain why you're so peculiar."

Anna spits in the dirt, just missing Theodore's big toe. Then she follows him into the store, keeping her hands in her pockets and remembering to swagger.

After the bright sunlight, it's dark inside, but Anna can see long strips of flypaper hanging from the ceiling, twirling in the breeze from the fan. She breathes in the musty odor of chicken feed mixed in with the smells of cheese and kerosene and floor wax.

Farm tools, overalls, and rubber boots hang from the ceiling, and the shelves are jammed with just about everything a person might need, from bolts of fabric to lamp oil, tools, and canned goods. The hodgepodge is very different from city stores that sell special things: food in one shop, clothing in another, hardware someplace else, and so on.

Mr. Buell is chatting with two men at the counter. When he sees Theodore and Anna, he smiles.

"Well, well, Theodore, what can I do for you today?" he asks.

Theodore takes the list from Anna and thrusts it across the counter. "Aunt Aggie needs these things."

Mr. Buell glances at the list and nods. Then he turns his attention to Anna. "Aren't you going to introduce me to your friend, Theodore? I don't recollect seeing him around here before."

Anna grins. Mr. Buell has just said "him." So far, so good. He thinks she's a boy.

Theodore takes a deep breath. "This here is Herman, Aunt Aggie's long-lost relative from Germany. His daddy ran off with a Dutch lady and now he's here for a visit."

"You don't say." Mr. Buell leans across the counter and peers at Anna's face. "I didn't know Aggie had relatives overseas."

"Guten tag, "Anna says politely, trying to remember the German she's learned from Mother.

"Good day, to you, too," says Mr. Buell.

Switching to English, Anna imitates her grandfather's accent. "Ich been pleased to meet you."

Mr. Buell chuckles. "Sehr angenehm, " he says. "Pleased to meet you, too!"

Anna's face turns red. She hadn't expected Mr. Buell to know German.

"Where are you from?" he asks. "What city?"

"Hanover," Anna says, glad she can remember where Grandfather was born.

"Ah, I know Hanover well," Mr. Buell says. "What street do you live on?"

Annas face turns redder. Why did she start this silly game? "Ich forgetten," she stammers, still trying to sound German.

Theodore rises on his toes to look Mr. Buell in the eye. "Can you please give us what Aunt Aggie needs?" he asks. "She wants to make lemonade for Uncle George. It has to be ready by noon, so we're in a hurry."

"Sure, sure." Mr. Buell winks at the other men. "It's not often I meet someone from my native land, you know. Such a handsome young lad. Almost too pretty to be a boy."

Anna stares at the floor. She will never set foot inside this store again.

Whistling a tune, Mr. Buell fills a bag with sacks of sugar, coffee, and flour and drops in six lemons. "That will be one dollar and three cents," he says.

Anna pulls the money out of her pocket and slaps it down on the counter. "Vee vant two peppermint sticks," she says, still trying. "Und some licorice, bitte."

"Ah, I like children who say please." Mr. Buell drops a handful of peppermint sticks into the bag and adds a handful of stringy black licorice. Handing the bag to Anna, he says, "Here you are Herman," he says. "Your candy and your change."

"Danke schön," Anna says, dropping ninety cents into her pocket.

"You are very welcome, indeed," Mr. Buell tells Anna. Turning to Theodore, he says, "If you see your aunt's niece Anna, be sure and say hello for me. I thought she was visiting this week, but I must have been mistaken."

Theodore gives Anna a push. "Let's go. Aunt Aggie needs these things right away."

"Auf Wiedersehen," Mr. Buell calls as Anna and Theodore leave the store.

Outside in the sunlight, Theodore glares at Anna. "I never felt like such a moron in my whole life!"

Anna scowls at Theodore. "It's all your fault. You should have told me Mr. Buell was German."

"I wish you really were a boy," Theodore says, "so I could punch you in the nose."

"Go ahead! Punch me!" Anna sets the grocery bag on the ground and doubles her fists. She's seen boys fight. She's sure she knows how to do it. "I'll punch you right back!"

Theodore makes a fist and punches Anna in the chin but not very hard. She punches him. He punches her a little harder. Anna's hat flies off. Her braids tumble down her back. Theodore grabs one and pulls. Anna screeches.

Suddenly, Mr. Buell is between them. "Children, children!" With one hand he grabs Theodore. With the other he grabs Anna. He holds the two of them apart and looks at them.

"My, my," he says. "Just look at Herman's braids. Is this how boys in Germany wear their hair nowadays?"

Theodore starts to laugh. Even though she's embarrassed, Anna laughs, too.

Mr. Buell chuckles. "It seems you rascals tried to play a trick on me."

"It was all Anna's idea," Theodore says. "I told her you'd never believe her, but she just had to go and act the fool."

Anna stops laughing. If Mr. Buell weren't still holding her arm, she'd punch Theodore for calling her a fool.

"Oh, but I did believe Anna," Mr. Buell says. "I never would have given you all that candy if I hadn't been so happy to see such a nice little boy from my native land."

Anna feels happy again. "I'm not a fool, after all," she tells Theodore, leaning around Mr. Buell to see him better. "You have me to thank for the extra candy."

"You have Anna to thank for this, too." Mr. Buell pulls two cold bottles of sarsaparilla out of a tub full of ice and water. "There you are," he says, handing them each one. "No more fighting, okay?"

Anna looks at Theodore. Theodore looks at Anna. They grin. A hot sunny day, two bottles of sarsaparilla, and all the candy they can eat. Being friends is definitely more fun than being enemies. At least for right now.

NINE

Princess Nell

THAT AFTERNOON, AUNT AGGIE SENDS THEODORE and Anna down to the end of the lane to wait for the mailman. It's about time for the Sears and Roebuck catalog to come. Aunt Aggie's be

en wanting one of the new gas ranges they sell. She's hoping this year Uncle George will say they can afford it.

"It will be a long wait," Theodore tells Anna. "Mr. O'Reilly stops and talks to everybody. He tells who got letters from far away, who had a death in the family, who had a marriage, who had a baptizing. He knows everything there is to know about all the folks in Beltsville."

Anna wonders if girls are allowed to be mailmen. Think of all the postcards she could read. Why, she'd learn all about the world and everyone in it. It's the most perfect job she can think of.

"I bet Mr. O'Reilly's told everybody in Beltsville you're here," Theodore adds.

Anna smiles. If Theodore is right, she's famous, at least in Beltsville. She wants to hear more of Mr. O'Reilly's gossip, but Uncle George calls Theodore to hoe the tomato patch.

Theodore makes a face Uncle George can't see. Anna knows he hates to hoe in the hot sun. "Tell me if the catalog comes," he tells Anna. Then he heads up the lane to meet Uncle George.

Left alone, Anna climbs on the fence and leans over so she can see way down the road. In the city, the streets would be full of people coming and going. But here there's not a person in sight, not a car, not even a horse pulling a wagon. Birds sing, a rabbit runs across the road, butterflies drift from one clump of wildflowers to the next, cicadas rasp in the tall grass. The air smells sweet.

Anna sits on the top rail of the fence, making a clover chain and whistling songs she learned in school, "The Battle Hymn of the Republic," "Maryland, My Maryland," "Oh, Susanna." She's glad Mother can't hear her. According to Mother, it's unladylike to whistle. Sometimes Anna thinks everything that's fun is unladylike. Going barefoot, wearing overalls, swimming in your drawers, getting dirty, whistling, spitting. Boys don't know how lucky they are.

Mister Death's Blue-Eyed Girls

Mister Death's Blue-Eyed Girls The Ghost of Crutchfield Hall

The Ghost of Crutchfield Hall Hear the Wind Blow

Hear the Wind Blow Time of the Witch

Time of the Witch The Girl in the Locked Room: A Ghost Story

The Girl in the Locked Room: A Ghost Story All the Lovely Bad Ones

All the Lovely Bad Ones One for Sorrow

One for Sorrow Deep and Dark and Dangerous

Deep and Dark and Dangerous Tallahassee Higgins

Tallahassee Higgins Promises to the Dead

Promises to the Dead Took: A Ghost Story

Took: A Ghost Story Following My Own Footsteps

Following My Own Footsteps Wait Till Helen Comes: A Ghost Story

Wait Till Helen Comes: A Ghost Story Where I Belong

Where I Belong The Spanish Kidnapping Disaster

The Spanish Kidnapping Disaster Look for Me by Moonlight

Look for Me by Moonlight The Old Willis Place

The Old Willis Place Closed for the Season

Closed for the Season As Ever, Gordy

As Ever, Gordy Anna on the Farm

Anna on the Farm The Doll in the Garden

The Doll in the Garden Daphne's Book

Daphne's Book Witch Catcher

Witch Catcher The Gentleman Outlaw and Me--Eli

The Gentleman Outlaw and Me--Eli Wait Till Helen Comes

Wait Till Helen Comes Took

Took A Haunting Collection

A Haunting Collection Anna All Year Round

Anna All Year Round The Girl in the Locked Room

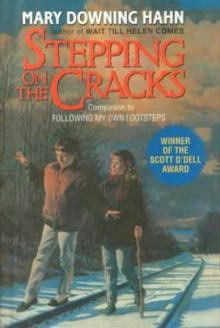

The Girl in the Locked Room Stepping on the Cracks

Stepping on the Cracks