- Home

- Mary Downing Hahn

Wait Till Helen Comes Page 3

Wait Till Helen Comes Read online

Page 3

“Do you believe in ghosts?” Michael leaned toward me. All he needed was a pipe in his mouth to make him the perfect scientist.

I shrugged. “I don’t know.” As usual, his rational approach was embarrassing me. I felt silly answering his questions. Pretending to yawn, I edged toward the door. “I think I’ll go to bed, Michael.”

He nodded. “If you hear any funny noises or see a face at the window, just yell for me,” he said as I started down the hall to Heather’s and my room.

I glared at him, sure now that I wouldn’t be able to sleep for fear of what might be creeping toward the church from the graveyard.

“Just kidding, Molly,” he whispered as I paused, my hand on my doorknob. “The only weird thing you’ll see tonight is Heather.”

Ignoring him, I tiptoed into the room. Except for the moonlight shining dimly through the window, it was dark, and I moved cautiously, not wanting to trip over anything and risk waking Heather. Pulling my pajamas out from under my pillow, I undressed and got into bed. I was anxious to fall asleep as quickly as possible so I wouldn’t lie there thinking about horror movies and scary stories.

But you know how it is. The more you want to sleep the more you stay awake, hearing every strange sound and translating it into footsteps in the hall, bony hands at the window, the moans of ghosts in the shrubbery. When I heard a sort of whimper, I stiffened in terror and prepared myself for the appearance of a hideous creature. Forcing myself at last to open my eyes, I saw nothing but Heather, her pale face almost hidden by her dark curls tumbling over the pillow. As I watched, she moaned again and tossed restlessly, mumbling something that sounded like “Mommy, Mommy.”

Turning my back, I grabbed my cassette player and put the earphones on. Soon all I heard was the voice of Julie Harris reading one of Emily Dickinson’s poems, a good inspiration for the poetry I planned to write this summer.

I woke up to the sound of a mower droning away outside. The sun was shining, and Heather’s bed was empty. Glancing at my watch, I saw that it was nine o’clock. Hoping that Michael hadn’t already disappeared in quest of new insects to add to his collection, I dressed and ran down the hall to the kitchen.

I found Heather and Mom sitting at the table, finishing their breakfast. Dave was already in the carriage house setting up his pottery workshop, and Mom said Michael was in the graveyard talking to Mr. Simmons.

“Who’s Mr. Simmons?” I asked, pouring milk on my cereal.

“He’s the graveyard’s caretaker. He comes once a month or so to mow the grass and tidy the place up.” Mom sipped her coffee. “He’s a nice old chap, about seventy or eighty years old, but he carries himself like a soldier.”

Remembering the height of the weeds, I had a feeling that Mr. Simmons had been on a vacation or something. “Maybe it won’t look so gloomy after he finishes,” I said.

Mom smiled and turned to Heather. “What would you like to do today, sweetie?” she asked.

Shoving her half-full bowl of cereal across the table, Heather got up and headed toward the back door.

“Where are you going?” Mom called after her.

The only answer she got was the sound of the screen door banging shut behind Heather.

“Oh, well, I guess she’ll be all right outside.” Mom went to the window over the sink and watched Heather amble across the lawn toward the hedge and the sound of the mower. “Poor Mr. Simmons. I guess she wants to see what he’s up to.”

She crossed the room and paused beside me. “I’ve got a lot to do, Molly. As soon as you finish eating, please go out and keep an eye on Heather. I don’t want her wandering off.”

“Can’t I stay in and help you?”

She patted my shoulder. “The nicest thing you can do for me is to look after Heather.”

Before I could say anything more, she left the room. Glumly I ate the rest of my cereal and went outside in search of Heather and Michael. By the time I got to the graveyard, Mr. Simmons had finished mowing. He was clipping and trimming the weeds around the tombstones, and Michael was raking the cut grass into a pile next to the wheelbarrow. Heather was sitting on a fallen tombstone trying clumsily to make a daisy chain. When she saw me hesitating at the gate, she said, “Molly’s afraid to come in here. She thinks something’s going to get her.”

Mr. Simmons looked up and smiled at me. “Well, good morning, Molly. Won’t you join us?”

Taking a deep breath, I walked toward him, careful, as usual, not to step on anybody’s grave. Now that the grass was cut, it was easier to see where it was safe to walk. In fact, the whole place looked at lot less scary than it had before.

“Mr. Simmons says this is a real old graveyard,” Michael told me. “The church was built way back in 1825, so some of the graves are 160 years old. Isn’t that something? The Civil War hadn’t even happened then. But nobody’s been buried here since 1950. Isn’t that right?” Michael turned to Mr. Simmons.

The old man nodded his head. “They filled the graveyard up, that’s what they did. Old Mrs. Perkins was the last one to get in.” He pointed at a pink stone with a shiny front. “Right there she is. My first-grade teacher.” He grinned and shook his head. “She’s not handing out any more report cards now, is she?”

Michael laughed, but I felt sad just thinking about Mrs. Perkins. “Caroline,” it said on the stone. “Dear, Departed Wife of John Albert Perkins. She will long be missed.”

“And right over here,” Mr. Simmons went on, “is where my mother and father are sleeping.” He rested his old hands on two stones. “I brought flowers for them and my baby sister, too.”

I looked at the mason jars full of wild flowers decorating the three graves. “They look very pretty,” I said, wondering if he felt sad. “It must be awful when a baby dies,” I added, staring at the tiny headstone marking his sister’s grave.

“They didn’t have the medicine then, you know,” he said. “Measles, chicken pox, whooping cough, scarlet fever, that’s what killed the children.”

As Michael nodded, glad that Mr. Simmons was backing up his own theories, Heather joined us. “Fire too,” she said. “Lots of people died in fires, didn’t they?”

Mr. Simmons looked a little surprised. “They did indeed,” he said.

“My mother died in a fire.” Heather dropped a dandelion on the baby’s grave and walked away.

Mr. Simmons watched her for a moment, then turned to us. “I thought she was your sister,” he said.

“No, her father married our mother.” Michael nudged the dandelion away from the baby’s grave with his bare toe. “She’s our stepsister.”

“Her mother died in a fire?” Mr. Simmons asked.

“When Heather was three. They were all alone in the house, and Heather almost died too. She was unconscious when the rescue squad found her,” I told him.

“Poor little thing,” he said sympathetically. Turning away, he returned to his work, clipping carefully around each stone and whistling. The sweet smell of cut grass drying in the hot sun filled the air, mingling with the aroma of Mr. Simmons’ pipe. A mockingbird perched on a tombstone and sang; butterflies flashed about, and for a while I forgot my fears and helped Michael scoop the grass cuttings into the wheelbarrow.

“You haven’t mowed under the tree,” I heard Heather say suddenly. She was frowning at Mr. Simmons’ back as he knelt at the base of the Berrys’ marble angel.

He squinted up at her. “Not enough grass under that old tree to bother with,” he said pleasantly.

“There’s weeds though.”

“I just tend to the tombstones.” Mr. Simmons returned his attention to the grass, but Heather didn’t take the hint.

“But there’s a grave there,” she said, her lip jutting out. “I saw it.”

Mr. Simmons straightened up and stared at her. “Couldn’t be. Too many roots to bury somebody there.”

“The tombstone is lying down in the weeds,” Heather insisted. “Come with me. I’ll show you.” She started walking t

oward the dense shade under the oak tree, and Mr. Simmons shrugged and followed her.

Michael turned to me. “Aren’t you coming with us, Molly?”

I started to go with them, but I felt my goose bumps coming back. The cheerfulness of the day was gone, as surely as if a cloud had covered the sun. Something was wrong; I could sense it if no one else could. Staying where I was, next to the relative safety of Mrs. Perkins’ shiny new tombstone, I watched the three of them step into the oak tree’s shadow. Heather pointed at something in the grass, and Mr. Simmons bent down to get a better look.

“Looks like you’re right,” I heard him say to Heather.

“Come here, Molly!” Michael called. “This is really interesting.”

As Heather smiled at me over her shoulder, daring me as she had before, I forced myself to join them. Mr. Simmons was struggling to right a small, weather-stained stone. “Well, I’ll be,” he said. “I’ve been tending these graves for twenty-some years, and I never knew this one was here. Never even looked for it.”

With the stone erect, he scraped away the dirt and moss to reveal the inscription. “‘H.E.H,’” he read out loud, tracing the letters with his fingers. “‘March 7, 1879–August 8, 1886. May she rest in peace.’” He shook his head and set to work pulling out the weeds growing around the base of the stone. “Strange, isn’t it?”

“Why is it strange?” Michael asked.

“Well, she was just a child. Seven years old. Where’s the rest of the family?”

“What do you mean?” Michael squatted beside him, staring at the gravestone.

“Well, look around, son. Families get buried together,” he said.

“That’s right. Like the Berry Patch.” Michael nodded astutely.

Mr. Simmons looked puzzled for a moment, but then he chuckled. “Yes, yes, the Berry Family. All together they are with their very own angel to watch over them.” He relit his pipe and stood up, gazing about the graveyard.

“The stones usually say ‘Beloved Daughter of’ or something like that,” he mused, “but here’s this child, all by herself. No name. Just the initials. No other grave close by. It just doesn’t seem right somehow.”

“It’s my initials,” Heather said suddenly, removing her thumb from her mouth and touching the stone lightly. “Heather Elizabeth Hill.”

“My age too,” she added as we all stared at her.

“Well, now, that is a coincidence,” Mr. Simmons said. Lopping away the last of the weeds, he took Heather’s hand and led her out into the sunlight. “I wouldn’t play here,” he said to her. “Even with the weeds gone, it’s a good place for snakes. Poison ivy, too, from the looks of it.” He gestured at the shiny green leaves flourishing in the shade and twisting up the oak’s trunk.

“I’m not afraid of snakes,” Heather said. “Or poison ivy either. I never get it.”

Mr. Simmons frowned down at her. “You listen to what I tell you, young lady. That’s the kind of shade a copperhead loves. One of them bites you, you’ll know it.”

Heather gave the old man a scornful look and pulled away from him. “I’ll play wherever I want to. You’re not my boss.” Then she stalked off, head high, black curls lifting in the breeze.

“Uppity little creature,” Mr. Simmons said. “How about giving me a hand with the wheelbarrow?” he asked Michael.

As the two of them trundled off toward the compost heap, I walked back to the house. Although Heather was nowhere in sight, I could hear Dave’s voice in the carriage house, and I supposed she’d gone in there to tell him how mean Mr. Simmons was.

Finding a shady spot on the back steps, I sat down and gazed across the yard at the oak tree standing guard over H.E.H.’s lonely grave. Why hadn’t the child’s name been carved on the tombstone? Why was it all alone? I shivered again, despite the heat, and wondered how I would feel if the initials had been mine instead of Heather’s.

5

AFTER LUNCH, Mom sent Heather and me to our room to finish unpacking. “I want every box emptied and all your things put where they belong,” she insisted as Heather started to whine in protest. “If you’re having trouble finding places for everything,” Mom added, “ask Molly to help you. That’s what big sisters are for.”

Without saying another word, Heather began unpacking, stuffing clothes into her bureau and books and toys onto the shelves on her side of the room. Ignoring the mess she was making, I concentrated on arranging my books and papers as neatly as possible. At least my side would look nice.

After a while, Heather lay down on her bed and shut her eyes. Thinking she’d gone to sleep, I finished putting my clothes into my bureau and lay down on my bed to read. I was so absorbed in Watership Down that I jumped when Heather suddenly spoke to me.

“What do you think that child’s name is?” She was still lying down, gazing up at the ceiling where the leaves of the maple cast ever-shifting patterns. “Do you think it could be Heather Elizabeth Hill?”

“Of course not. That’s your name.”

“Suppose the initials were M.A.C?” Heather whispered.

“Those are my initials.” I frowned at her.

“Would you be scared?”

I shrugged. “Not especially. Why? Are you scared?”

She sat up and shook her head. “No. I think it’s interesting, that’s all.” She smiled at me. “But you would be scared, Molly. I know you’d be. You’re afraid right now, and they aren’t even your initials.”

“Don’t be silly.” I opened my book again. “If you’re finished asking questions, I’d like to get back to my reading.”

“That’s a dumb story,” Heather said, getting up and staring out the window. “I hate rabbits. Who cares what happens to them?”

Ignoring her, I concentrated hard on Fiver’s desperate attempts to warn the rabbits that danger was coming. This was the second time I’d read the book, and Fiver was my favorite character. I knew I would enjoy the story more this time, knowing that he was going to be all right.

Heather didn’t say anything more. When I glanced at her to see what she was doing, she was still standing at the window gazing out at the graveyard as silently as a marble angel contemplating eternity.

As the days passed, the five of us got caught up in our own routines. From morning until night, Dave worked at the pottery wheel in the carriage house, throwing bowls, plates, mugs, pitchers, and jugs, mixing glazes, and tending his kiln, trying to get ready for a big August Craft Show. Although he didn’t seem to mind our coming in and out, watching him work, he wasn’t particularly interested in what we were doing. As long as we turned up for meals and bedtime, he didn’t worry about us.

Mom was just as bad. She was terribly excited about having a real studio after so many years of setting up her easel in the corner of the kitchen or the bedroom, wherever she could find some unwanted space. She was working on a large painting of a barn. The colors were soft and muted, and all the edges were hazy as if the morning sun hadn’t quite broken through the fog. You could almost smell the damp boards when you looked at it.

But Mom didn’t like to be watched while she was painting; it ruined her concentration and made her self-conscious. So she’d always tell me to go outside and play. I guess she felt that we were all safe out here in the country. The things she worried about in Baltimore—drug dealers, child molesters, speeding cars—didn’t exist in Holwell. The only thing she ever asked me to do was to keep an eye on Heather. She thought both Michael and I, being older, should take care of her.

Of course, that was the one thing neither of us did. Every morning, as soon as Dave disappeared into the carriage house and Mom went to her loft, Michael grabbed his butterfly net and kill jar and ran to the woods in pursuit of insects to add to his collection. Although I could have gone with him (and sometimes did), I usually took a book and my journal and wandered off somewhere to read or write.

And Heather? For a long time I had no idea where she went or how she spent her time. She might start out o

n the couch next to me, coloring or reading or watching television. Then, without my actually noticing, she’d disappear. She reminded me of a cat I used to own; one minute he’d be curled up next to me, and the next minute he’d be gone without making a sound.

One hot afternoon, I went outside looking for something to do. The air was hot and heavy with humidity, and I decided to walk down by the creek, maybe wade or something, just to cool off. Leaving my book on the bank, I splashed through the water without realizing how close I was getting to the graveyard. When I looked up and saw the tombstones above me, I hesitated, thinking I’d turn back in the direction of the cows.

Then I heard a voice. Was it Heather’s? The breeze swirled the leaves, the creek chattered over stones, birds sang, insects chirped and buzzed, making it impossible to be sure who was speaking. Uneasily, I climbed the bank and tiptoed down the path beside the graveyard.

I found Heather sitting in the shade staring at the small tombstone under the oak tree. On the grave, she had placed a peanut butter jar filled with black-eyed Susans and Queen Anne’s lace. As I watched, scarcely daring to breathe, she said something in a voice too low for me to hear, her hands flashing in the shadows as she gestured nervously.

Then she sat back, her mouth half-open, her eyes half-closed, nodding her head as if she were in a trance. All around me the leaves rustled, and I shivered, sure that the noise they made was hiding words from me that were audible to Heather. Convinced that she was in danger, I leaned toward her, peering through a tangle of honeysuckle, wondering what I should do.

“Oh, Helen,” Heather said suddenly, her voice louder. “Will you really be my friend? I’ll do anything you say—I promise I will—if you’ll be my friend.”

Again she was silent, her head tilted to one side, a smile twitching the comers of her mouth. The breeze blew again, making a dry sound, a whispering, and Heather nodded. “I’ll wait for you, Helen. When you come, I’ll be the best friend you ever had, cross my heart.”

Mister Death's Blue-Eyed Girls

Mister Death's Blue-Eyed Girls The Ghost of Crutchfield Hall

The Ghost of Crutchfield Hall Hear the Wind Blow

Hear the Wind Blow Time of the Witch

Time of the Witch The Girl in the Locked Room: A Ghost Story

The Girl in the Locked Room: A Ghost Story All the Lovely Bad Ones

All the Lovely Bad Ones One for Sorrow

One for Sorrow Deep and Dark and Dangerous

Deep and Dark and Dangerous Tallahassee Higgins

Tallahassee Higgins Promises to the Dead

Promises to the Dead Took: A Ghost Story

Took: A Ghost Story Following My Own Footsteps

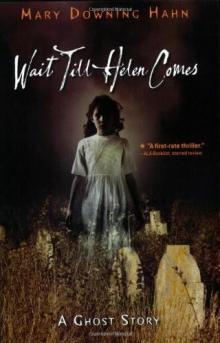

Following My Own Footsteps Wait Till Helen Comes: A Ghost Story

Wait Till Helen Comes: A Ghost Story Where I Belong

Where I Belong The Spanish Kidnapping Disaster

The Spanish Kidnapping Disaster Look for Me by Moonlight

Look for Me by Moonlight The Old Willis Place

The Old Willis Place Closed for the Season

Closed for the Season As Ever, Gordy

As Ever, Gordy Anna on the Farm

Anna on the Farm The Doll in the Garden

The Doll in the Garden Daphne's Book

Daphne's Book Witch Catcher

Witch Catcher The Gentleman Outlaw and Me--Eli

The Gentleman Outlaw and Me--Eli Wait Till Helen Comes

Wait Till Helen Comes Took

Took A Haunting Collection

A Haunting Collection Anna All Year Round

Anna All Year Round The Girl in the Locked Room

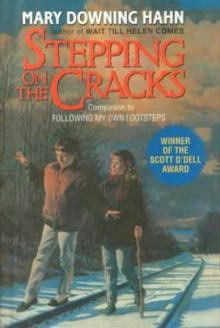

The Girl in the Locked Room Stepping on the Cracks

Stepping on the Cracks