- Home

- Mary Downing Hahn

The Puppet's Payback and Other Chilling Tales Page 2

The Puppet's Payback and Other Chilling Tales Read online

Page 2

Spooked by the sound, I walked faster. But I heard it again. And again. A small voice calling for help. Definitely not a cat.

Almost hidden in the fog, a little girl stood behind the cemetery’s gate, clutching the bars like a prisoner.

“Please help me!” she cried. “I can’t get out.”

She sounded so desperate and looked so helpless, I crossed the street to speak to her. “How did you get into the cemetery?” I asked. “What were you doing in there after dark?”

She twisted a long strand of dark hair around her finger and looked worried. “It’s my own fault, you see. I wandered away from my companions and took the wrong path, and now I cannot open the gate.”

“Your friends left you here all by yourself?”

“Please,” she begged. “Just open the gate and let me out. I can’t bear to remain another moment in this dreadful place.”

Although I expected the gate to be locked, I tugged and pulled, and slowly, with a loud grating and scraping noise, it opened just wide enough for the girl to slip out.

“Oh, thank you. Thank you. I am eternally grateful to you.” She smiled up at me. “My name is Allegra. What is yours?”

“It’s William.”

“William.” She thought a moment and smiled. “William is a good name. An honest sort of name. A boy with the name of William can be trusted.”

It was a strange thing to say, but it was a compliment, I guessed. “I’ve never known anyone named Allegra,” I said, “but I’m sure it’s a good name too.”

“I’m glad you think so.”

Allegra took my hand. “The fog is so confusing,” she said. “I’m not certain which way to go. May I ask you to walk me home? If it’s not too much trouble, that is.”

“It’s no trouble at all. Where do you live?” Truthfully, walking her home would make me late for dinner, but how could I possibly leave a little girl to find her way all by herself?

“My house is number 213 Poplar Street. Do you know of it?”

“Of course I know where Poplar Street is. I’ve lived in this town all my life.”

“All your life? My goodness. We never stay in one place long.” She held my hand tighter. “Is Poplar Street far from here?”

“Not too far. Just on the other side of the cemetery.”

“I’d prefer not to walk beside the cemetery. May we go a different way?”

“Sure.” She had no idea how glad she’d just made me. All the time we’d been standing by the gate, I’d been hearing strange sounds and spotting things moving among the tombstones. I knew my imagination was playing tricks on me again, but I was more than happy to put as much distance between us and the cemetery as possible.

Holding her hand, I led her to the corner and turned down Chestnut Street. As soon as the cemetery was out of sight, I took a deep breath and slowed down—no need to tire Allegra.

“Why did your friends leave you in the cemetery?” I asked her. “Were they trying to scare you or something? It seems like a mean thing to do to a kid as young as you. My sister would have been scared to death in a situation like that.”

Allegra shrugged. “Oh, they’re accustomed to my ‘disappearing acts,’ as they call them. I often wander off by myself. They know I’ll either find my way home or someone like you will lead me there.”

I stared at her, perplexed. She was the oddest girl I’d ever met. Most kids were scared of both the dark and cemeteries. But Allegra acted like it was no big deal to be abandoned on a dark, foggy night—in a cemetery no less.

“But it’s so dark,” I said, “and the fog is so creepy.”

“Truly my companions would worry more about me being lost in the daylight than in the dark.”

I laughed. “You have a weird sense of humor, Allegra.”

She gave me an angry look. “I was not trying to be funny.”

“I’m sorry. I just thought . . .” The frown on her face deepened, and I shut my mouth.

We walked on without talking. A passing car’s lights illuminated Allegra’s pale face. Without even glancing at me, she stared straight ahead, frowning as if she were still angry. After we’d walked another block in silence, I decided to ask her a question that couldn’t possibly annoy her.

“Do you go to Hargrove Elementary School? My sister Rachel is in second grade. You must be around her age. Maybe you know her.”

“I don’t attend school. I have special lessons.”

“Oh, you’re homeschooled.” That made sense. She probably spent a lot of time by herself. Maybe that explained why she spoke like someone in an old-fashioned book. And why she seemed way older than Rachel.

“Do you like staying home, instead of going to school?” I asked her.

“Sometimes I’d prefer to attend a real school. It’s ever so lonely not to have friends.”

“I could bring Rachel to your house. Maybe you’d like each other.”

“That isn’t possible. I am not allowed to socialize with other children.”

“But what about the kids you were with in the cemetery?”

Allegra laughed. “Oh my goodness. What a funny thought. Why do you think of my companions as children?”

“Well, most kids are friends with kids their own age—like Reilly and me or Rachel and Colleen.” I paused in case she wanted to say something, but she contemplated her shoes, which were shiny and as fancy as her dress. “If your friends aren’t children, how do you play with them? What do you do?”

“Your questions are growing extremely tiresome, William.” Allegra freed her hand from mine and ran up the street ahead of me. “How far is it to Poplar Street now?” she called over her shoulder.

“Wait!” I hurried after her, afraid I’d lose her in the fog.

She stopped and watched me run toward her. I couldn’t tell if she was still mad.

“I’m sorry. I didn’t mean to be tiresome,” I told her, “but you’re so mysterious. It must be past dinnertime. Won’t your parents be worried about you?”

Allegra smiled that odd little smile of hers, just a slight upturn of her lips. “I told you I often wander. No one worries if I’m late. They know I can take care of myself.”

“But what if a strange man had come along and seen you in the cemetery? The kind of men you hear about on the evening news . . . You know what I mean. It’s dangerous for you to be out after dark by yourself.”

“I said you needn’t worry about me. Perhaps you should worry about yourself instead.”

Allegra sounded annoyed again. I jammed my hands into my pockets and walked on beside her. “Why should I worry about myself?”

“Bad things happen to boys too.”

“Not very often,” I muttered. “Not in this town, anyway.”

Allegra looked at me. “Bad things happen everywhere, William.”

She sounded sad, like maybe she knew more about bad things than I did.

Taking my hand again, she asked, “Are we almost to Poplar Street?”

“It’s only a couple more blocks,” I told her. “Are you cold? Your dress doesn’t look very warm.”

“It’s my favorite frock.” Allegra smoothed the skirt. “Isn’t it pretty?”

“Rachel would love to have one just like it.”

“Your parents would have difficulty finding a dress of this quality. It was made in Paris, especially for me.”

“Are you from France?” Coming from a foreign country might explain her peculiarities.

“I wasn’t born there, if that’s what you mean. We travel to Europe frequently.”

“Lucky you. I’ve never been anywhere except California, for my grandmother’s funeral.”

Allegra sighed. “Traveling becomes tiresome after a while—packing, unpacking, boarding ships, leaving ships.” She yawned as if even talking about it bored her.

“Well, when I grow up, I’m going to travel around the world, me and my friend Reilly. We’ll never be bored.”

Allegra shrugged. We stopped on a co

rner, and I read the street sign through the fog. “This is Poplar Street. Is your house to the left or the right?”

Allegra looked in both directions. “The fog is so thick. I’m not certain which way to go.”

“Let’s turn right. If the house numbers are bigger than 213, we’ll turn around and go the other way.”

Of course, it didn’t turn out to be that easy. The houses on Poplar were the oldest in town. They were big and set far apart on wide lawns. Some had porch lights, some didn’t. The fog made it hard to read the numbers. To make it worse, we blundered along for a block or two only to discover we’d gone the wrong way. Frustrated, we turned around and retraced our steps.

As we passed a particularly nice house, I said, “Mom would love to live on this street.”

“Would you like to live here, William?”

“Probably not. Just think of all the leaves I’d have to rake and the grass I’d have to mow.” I looked at her. “Do you like living here?”

“Sometimes. Perhaps I’d enjoy it more if I had a playmate.”

“Lots of kids live in this neighborhood. Rachel is friends with Colleen Davis, who lives one block over on Walnut Street. Do you know her?”

She shook her head and looked at me sadly. “I told you I’m not allowed to play with other children.”

“But—”

“We have certain standards.”

“You mean those kids aren’t good enough to be your friends?”

Allegra scowled. “You’re asking questions again, William.” She sighed and stared at a house number. “217—we’re almost there.” She walked more slowly, her head down, and finally came to a complete stop beside a grove of pine trees that hid her house from sight.

“I thought you were in a hurry to get home,” I said.

She seized my hand. “Do you like me, William?”

“Sure I do. Why wouldn’t I?”

She looked at me so intensely I was uncomfortable. I’d never noticed how pale her eyes were and how small her pupils. Suddenly uneasy, I took a step backward.

Her stare grew harder, colder. “Suppose I’m not as sweet as you seem to think I am. Suppose I never needed you to rescue me or to walk me home. Suppose I’ve just been pretending all along.”

I stared at Allegra, confused by the change in her. “Why would you pretend?”

She moved closer to me, and I took another step backward. “Suppose you are the one in danger.” Her eyes caught the light of a streetlamp. They seemed to be paler.

“What are you talking about, Allegra? I don’t understand.”

Suddenly she turned away and freed me from the spell of her eyes. Without looking at me, she said, “You have been kind to me, William, but you must leave now. I am not your friend. You must not expect me to be what I cannot be.”

“But, Allegra, don’t you want me to come home with you? Your parents might be mad at you. I can explain why you’re late.”

“No!” she cried. “They must think I came home alone.”

“I don’t understand.”

“Believe me, it’s better not to understand.” She made a strange clicking noise with her teeth, like the sound my cat makes when it sees a bird. “Go home! And don’t come back!” She ran toward her house. The gate opened and clanged shut behind her.

Hoping the fog hid me, I followed Allegra as far as her gate. I watched her run up the front steps. I saw the door open. A shadowy figure drew Allegra inside. Before the door slammed shut, I heard a deep voice say, “You promised to find someone, Allegra—”

I stared at the closed door. The windows of the house were dark. The only sound was the murmuring of the pine trees behind me.

Finally, I gave up and walked away. Trudging along the familiar sidewalks, I felt lost even though I knew where I was.

Why had Allegra told me to run away and not come back? Was it some sort of game I didn’t know how to play? She’d gotten into my head and disturbed me. Confused me. Maybe I’d imagined the whole thing. Maybe I’d never let anyone out of the cemetery, maybe I hadn’t walked anyone home.

I was thinking so hard I didn’t see the Volvo until it pulled up beside me and Dad opened the door.

“I’ve been driving all over town looking for you,” he said. “Your mother is worried sick.”

When we got home, I told Mom my phone was dead and I’d gotten lost in the fog. I’m not sure why I didn’t mention Allegra. I just didn’t think I could explain how strange she was.

* * *

The next day, I decided to go to Allegra’s house. I pictured myself knocking on the door and telling her parents I’d brought Allegra home last night. I’d say I wanted to see her again. The worst her parents could do was slam the door in my face and tell me not to come back. But there was a chance I’d see Allegra in her yard or at a window and we could talk. She was a mystery I needed to solve.

When I reached Poplar Street, I headed down the sidewalk toward number 213. When I reached the grove of pine trees, I stopped and went over what I’d say when I met Allegra’s parents.

Hoping I’d figured out the right thing to tell them, I walked past the trees and stopped so fast I almost fell over my own feet.

Where the lawn should have been, I saw a field of dead weeds. Overgrown bushes hid the porch. Boards covered the windows. The roof sagged. The siding was bare weathered wood. The chimney leaned to one side.

Thinking I’d come to the wrong address, I walked to the next house and checked the number—215, in brass numerals over the front door.

I turned back and pushed the rusty gate open; 213 was painted on one of the pillars on the front porch. The paint on the door was cracked and peeling like dead skin. Piles of leaves lay in drifts against the splintered porch railings.

When I lifted the knocker, it came off in my hand. So I pounded on the door. “Is anyone home?” I shouted. “It’s me, William.”

“Hey!” somebody yelled. “Didn’t you see the ‘No Trespassing’ sign?”

I turned around. A kid stood on the sidewalk scowling at me. I’d seen him at school, but he was a year ahead of me, and I didn’t know his name.

I pushed through the weeds and joined him on the sidewalk. “Sorry, I didn’t see the sign. Do you know who lives here?”

“Ghosts,” the boy said. “It’s haunted.” He laughed. “At least that’s what some people say. Me, I don’t believe in that stuff.”

“But I was here last night. I brought a little girl to this house. She said she lived here.”

“She must have been playing a prank. Nobody’s lived there for years. It ought to be torn down, but Dad says there’s some problem with the deed.”

“Her name is Allegra. Do you know her?”

“I know every kid on Poplar Street. I can tell you there’s nobody named Allegra.” He slapped my back. “Hey, see you later. Got to go—soccer practice.”

When he was out of sight, I walked around the corner and saw an alley running between Allegra’s house and the one behind it. On the Poplar Street side of the alley, a tall weather-beaten fence hid everything but the top story of 213, but I found a gap big enough to squeeze through.

The house looked even worse from the back. The same tall weeds filled the yard. Almost hidden in them was what looked like the ruins of an old carriage. Junk of all sorts was scattered everywhere, shingles from the roof, boards and bricks, bottles and cans, a broken chair, a cracked mirror. It looked like people had been throwing their trash over the fence for years.

A trapdoor to the cellar was wide open, like an invitation to come inside. The steps sagged and one was missing, but I climbed down carefully. The stale air stank of mold and mildew and damp earth.

For a moment, I stood still, almost afraid to move. The place had a bad feeling, as if terrible things had happened there. Sorrow and misery and dark thoughts floated in the air. I imagined them clinging to my skin and hair and clothes.

I looked over my shoulder at the sky outside the cellar door. I should h

ave climbed back up the steps and gone home, but I was too obsessed with finding Allegra to be sensible.

I groped my way through the cellar. Bottles rolled under my feet. Boxes split open in the damp air spilled moldy books and papers everywhere. A rusty furnace big enough to heat the world crouched in a dark corner.

At last I found the stairs to the first floor and climbed them slowly, one at a time, feeling my way upward. I knew by now that Allegra couldn’t possibly be here, but maybe she’d left something behind that would tell me where she’d gone—or who she was.

The door at the top of the steps was warped. Pushing hard, I forced it open and almost fell into a hallway. Boarded-up windows let in some light, and I made my way into what must have been the parlor. Dust covered the floor, as thick as a gray carpet. Piles of dead leaves lay in the corners. The walls were streaked and stained and crumbling. Mice scrabbled inside the walls. Cobwebs swayed in a breeze, and the bones of small animals and birds who’d died in this place littered the floor.

In the dining room, a large table was set for dinner. Carved wooden chairs surrounded it, some tipped over, some still standing. A huge chandelier draped with cobwebs hung from the sagging ceiling.

Faded paintings hung crooked on the walls; rotting curtains draped the windows; rusty pots and pans and broken dishes filled the kitchen sink; books in heaps lay on the floor, ruined with mildew.

I tiptoed up a grand staircase to the second floor. The bedrooms were like the rooms below, full of broken, dusty furniture. Rain had poured down the walls from holes in the roof, leaving heaps of crumbling plaster and decayed wallpaper.

In one small room, I found a child-size bed and rocking chair. An old doll sprawled in a corner, her hair gone and her dress in rags. One eye was open and the other shut. She looked like a dead child.

I went back downstairs. In the parlor, a thick photograph album lay open on the floor. I kneeled and turned its pages slowly, lingering on each faded face as if I might find a clue to the history of this house. I looked at mustached men wearing dark suit jackets over stiff-collared shirts, ties knotted at their throats, their hair neatly parted in the middle; women in fancy dresses with huge puffy sleeves, their hair hidden by large feathered hats; and babies in long white dresses, boys in sailor suits, girls wearing dresses like the one Allegra had worn. A “frock,” she had called it. A frock made in Paris especially for her.

Mister Death's Blue-Eyed Girls

Mister Death's Blue-Eyed Girls The Ghost of Crutchfield Hall

The Ghost of Crutchfield Hall Hear the Wind Blow

Hear the Wind Blow Time of the Witch

Time of the Witch The Girl in the Locked Room: A Ghost Story

The Girl in the Locked Room: A Ghost Story All the Lovely Bad Ones

All the Lovely Bad Ones One for Sorrow

One for Sorrow Deep and Dark and Dangerous

Deep and Dark and Dangerous Tallahassee Higgins

Tallahassee Higgins Promises to the Dead

Promises to the Dead Took: A Ghost Story

Took: A Ghost Story Following My Own Footsteps

Following My Own Footsteps Wait Till Helen Comes: A Ghost Story

Wait Till Helen Comes: A Ghost Story Where I Belong

Where I Belong The Spanish Kidnapping Disaster

The Spanish Kidnapping Disaster Look for Me by Moonlight

Look for Me by Moonlight The Old Willis Place

The Old Willis Place Closed for the Season

Closed for the Season As Ever, Gordy

As Ever, Gordy Anna on the Farm

Anna on the Farm The Doll in the Garden

The Doll in the Garden Daphne's Book

Daphne's Book Witch Catcher

Witch Catcher The Gentleman Outlaw and Me--Eli

The Gentleman Outlaw and Me--Eli Wait Till Helen Comes

Wait Till Helen Comes Took

Took A Haunting Collection

A Haunting Collection Anna All Year Round

Anna All Year Round The Girl in the Locked Room

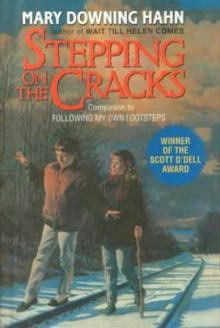

The Girl in the Locked Room Stepping on the Cracks

Stepping on the Cracks