- Home

- Mary Downing Hahn

Hear the Wind Blow Page 2

Hear the Wind Blow Read online

Page 2

The wind thumped the windows as she spoke, shaking the glass as if it meant to break into the room. I knew Mama was thinking about Avery again. We needed him so badly, it made me hate him sometimes. Why had he left me to take care of everything, and me just thirteen years old? When he came home, I'd tell him a thing or two.

"Can you take Rachel to the kitchen and feed her some of that stew?" Mama asked me. "I want to sit here a spell and watch this poor young man."

Rachel fussed a bit, but she followed me downstairs and seated herself at the table. I ladled possum stew into two bowls and sat down opposite her. I'd caught the varmint myself in one of Papa's traps, and I was mighty pleased with the way Mama had cooked him up.

Except for the wind howling around the house, the room was quiet. And warm from the fire in the woodstove. I was glad I'd collected a good pile of logs before the storm commenced.

After a while Rachel put down her spoon and leaned toward me, her face scrunched in worry. "Do you think the Yankees are searching for him?"

"I hope not."

Rachel turned to the window. Dark was falling fast and we could see our reflections in the glass, Rachel in her pigtails and me with my hair hanging in my eyes. Behind us, the kitchen looked snug and safe, yellow with lamplight.

"They could be out there in the dark right now," Rachel whispered, "watching us."

As she spoke, the wind hit the house hard, driving cold air through every crack. Rachel and I both shivered, partly from the draft and partly from fear. Suddenly, the kitchen didn't seem so safe after all.

"Those Federals won't go anywhere in this snow," I told her. "They're huddled around their campfires somewhere faraway, waiting for spring to recommence fighting."

"I've heard tell the Yankees are demons from hell," Rachel said. "Maybe they can follow a man by his smell, like the devil can."

Even though Rachel was merely a child, she was beginning to scare the beejeebers out of me. Hadn't I heard older folks say the same thing about the Yankees? I scraped the last bit of gravy out of my bowl and got to my feet. "Let's take Mama some stew and then go to bed," I said. "We'll be warm and snug under the blankets."

For once Rachel agreed with me. I carried the bowl of stew upstairs, and she followed with a chunk of bread. Mama was sitting in the rocker beside the bed. Even though James Marshall had swallowed every drop of her remedy, he still looked mighty sick to me.

"We brought you something to eat," Rachel told Mama.

Mama smiled at us. "Set it down on the bureau," she said. "I'll eat it later."

Rachel drew closer to Mama. "Is he getting any better?" she whispered.

Mama sighed. "He's no worse, thank the Lord."

"Is he fixing to die?" Rachel asked.

Mama hushed her. "Go on to bed, child."

We did as Mama said. Long after Rachel fell asleep, I lay awake, listening to the wind, thinking what a scary sound it made. Like the souls of the dead out there in the cold and the dark, wailing to be in their beds again, warm and snug. I pictured Avery sleeping in a tent somewhere, huddled under his blankets. And men like James Marshall alone and wandering the night like lost souls themselves. And officers in snug shelters, planning battles and dreaming of glory.

I fell asleep thinking I might ride away with James Marshall when he recovered. I'd find Avery and bring him home and make him do his share to protect Mama and Rachel. We needed him a sight more than General Robert E. Lee did.

2

I WOKE TO A COLD, gray dawn and went down the hall to check on James Marshall. Mama was asleep in the chair beside the bed, looking weary even in repose, but James Marshall was awake. He raised his hand to signify he saw me, and I crept close to him.

"How are you feeling?" I whispered.

"Poorly," he murmured, "but better than yesterday."

Even though we'd kept our voices low, Mama's eyes opened. She always did sleep as light as a cat. Leaning toward James Marshall, she laid a hand on his forehead. "Still feverish," she said, "but not near as hot as last night. My remedy must be helping."

James Marshall smiled. "I surely hope so, ma'am, for that is without a doubt the worst concoction I ever swallowed."

Mama's face brightened. "Only a man who's recovering complains about the taste of things." She turned to me. "Go on and get the stove fired up for cooking, Haswell."

"And see to my horse, please," James Marshall added.

I glanced at Mama and she nodded. "Tend to the horse first. And see to Clarissa."

When I opened the kitchen door, the wind hit me hard. The snow had stopped, but it lay mighty deep, especially the drifts against the side of the barn. It was hard work crossing the yard. The horse was on his feet, looking better. I fed him some oats leftover from our own horses and draped a blanket over his back. While he ate, I stroked his neck and whispered to him, for he'd been ridden hard and needed some extra comforting. He was a good horse, a black gelding with fine legs and a handsome face. Intelligent, I thought. And loyal. Not the sort of horse we'd ever owned. We were farmers, and our horses had to work the fields and pull wagons.

After I fed Clarissa, I walked back to the house, thinking about James Marshall and his family. It could be they were wealthy, owning a fine horse like that. Or it could be he stole the horse from the Yankees.

While I was feeding the fire in the kitchen, Rachel came downstairs. "James Marshall's feeling better, Mama claims, though he doesn't look real good to me. Most ashyfaced man I ever did see."

Without expecting an answer, she went to the window and peered out. "Just look at all that snow, Haswell. It's the most I've seen in my whole entire life. If James Marshall hadn't come to our house, both him and his horse would be dead and buried in it."

"You are positively the most morbidminded child in the state of Virginia," I said.

"What's that mean?" Rachel looked offended that I knew a word she didn't.

"Morbid? It means you're always thinking gloomy thoughts about death and dying."

Rachel smiled. "Morbid," she repeated, "moooor-bid. It has the saddest sound. Don't you just love words that sound like what they mean?"

I poked the fire. "I've never thought about that."

Rachel stuck out her tongue, her usual response, and picked up her doll. "Oh, Sophia," she crooned, "did you know you have a moooor-bid mama?"

Our mama came down then and told me to go up and sit with James Marshall a spell while she fixed breakfast. Rachel started to follow me, but Mama told her to stay and give her a hand with the oatmeal. Silently I thanked the Lord for small favors.

James Marshall was awake. He had the sharpest blue eyes I ever saw, but they weren't burning bright with fever this morning. "Did you see to my horse?" he asked.

"I did, and he's looking a sight better than you."

James Marshall smiled. "I'm glad to hear that."

"He's a mighty fine horse," I said.

"He is indeed. I call him Warrior. I've had him since I was about your age. He was my thirteenth-birthday present."

"That was a grand gift." I spoke with some envy. My thirteenth birthday had come and gone without much notice, like most of the ones before it.

"Papa has a horse farm south of here, not far from Harrisonburg. He breeds horses. Or he did before the war. Most of his herd was taken by the army, both North and South."

James Marshall lay back on his pillow and gazed at the ceiling. "As soon as I'm strong enough, I'll be on my way. I don't want to bring the Yankees here."

"Were they following you?"

"I think I lost them. We all scattered after the raid. That bullet slowed me down, but I had good cover in the woods. They didn't see which way I went. Probably thought I was dead." He paused a moment, as if he were contemplating his close call with eternity. "Is your father in the fighting?"

"Papa served under General Stonewall Jackson himself till Chancellorsville." I tugged at a feather poking out of the quilt, suddenly conscious of the voices in the wind howling outside

in the cold. Somehow it seemed shameful to tell James Marshall that Papa had died from dysentery. I was tempted to lie and say he'd been killed in battle, a hero. So I shifted the subject somewhat.

"Papa was one of the guards who took Stonewall to Guinea Station after he lost his arm. He was there when Stonewall died."

"That was a great loss," James Marshall said softly. "The South never had a finer general than Stonewall Jackson."

"Did you hear what Stonewall said before he died?" I asked.

James Marshall nodded. "His last words were, 'Let us cross the river and rest in the shade of the trees.' People say he looked as if he really saw the river and the trees instead of the bedroom wall."

"Papa said it was the River Jordan he saw. Is that what you think?"

"Most certainly. All of us will cross it one day and rest in the shade." James Marshall looked out the window at the bare trees shivering in the wind. He turned back to me, his blue eyes searching my face. "Will you do something for me, Haswell?"

"Of course." Though I didn't feel comfortable saying it, I'd do anything he asked me.

"There's a letter in my pocket." He pointed to his greatcoat, which Mama had hung on the back of a chair. "It's addressed to my father. If I die of this wound, promise you'll see he receives it."

"You won't die," I said, "but I'll promise anyway."

"Go and get it," he said. "Keep it safe."

I reached into his coat pockets reluctantly. Even though he'd told me to do it, it seemed like stealing somehow. I pulled out a dirty, ragged envelope and held it up so he could see. "Is this it?"

James Marshall nodded and held out his hand for the letter. He studied it and gave it back. "I guess the postman will be able to read my handwriting."

He watched me slide the envelope into my pants pocket. I thought he might want to sleep, but when I headed for the door, he stopped me. "Sit down, Haswell. You never did finish telling me about your father."

It seemed I hadn't distracted James Marshall after all. I settled on the quilt and tugged at that same old feather. "Papa died in Richmond while he was on guard duty. They sent his unit there after Chancellorsville—you know, to give them a rest." I paused and added, "After all the fighting he saw, he went and died of dysentery."

"Now that's a shame." James Marshall shook his head. "Your poor mama. She's got you and your sister to take care of. And a farm as well. Can't be easy for her."

"When the war's over, my brother, Avery, will come home and help me with the farm. He ran off to join the war not long after Papa died."

"Do you know where is he now?"

"He's been at Petersburg since last summer when the siege began. Every now and then he manages to send us a letter."

"From what I hear, that's a bad place to be and mighty hard to get out of. Folks there have come to eating dogs, cats, rats, just about anything."

"Avery says they eat what they can get," I muttered. "The Yankees have cut off everything. Nothing goes in, nothing goes out."

"It's a cruel war." James Marshall glanced at me. "How old is your brother?"

"Avery's sixteen, just three years older than I am."

"That's how old I was when I left home to fight with Mosby's men."

"You're with Mosby?" I stared at him with awe. John Singleton Mosby was the smartest man in Virginia, and the boldest. There was nothing he couldn't get away with. Horses, food, ammunition. Why, that man could walk right into a Northern camp and leave with whatever he fancied, and none the wiser till he was safely away.

James Marshall smiled. "Everything you hear about that wily fox is true. That's why I joined his Rangers."

"Best not tell Mama who you ride with," I said. "The Yankees hate Mosby. She's already scared of what they'll do to us if they find you here."

He nodded as if he understood. For a while we sat together quietly, listening to the wind. "The truth is, Mama doesn't care which side wins anymore," I said. "I heard her say so herself. She just wants the killing to stop. And Avery to come home safe."

James Marshall frowned. "The South is worth fighting for. Even dying for. We can't have Yankees telling us what to do. Doesn't your mama understand that?"

"Well, you know how ladies are. They don't appreciate the art of war." I pulled so hard at the feather it came out of the quilt. Mama would have slapped my hand if she'd seen what I'd done. Good thing she was still rattling pans in the kitchen and fussing at Rachel.

"Least that's what Papa said," I went on. "He tried and tried to explain old-time heroes like Achilles and Alexander the Great and Horatio, but Mama wasn't interested in their deeds. She said the world doesn't need any more heroes. According to her, we'd all be better off if men stayed home and minded their own patch."

James Marshall smiled at that and so did I, for it was funny to picture the heroes of history plowing fields or hoeing gardens, living to be old and gray. A man didn't win fame and glory that way.

"Do you know your Homer?" James Marshall asked.

I nodded. "Papa was a scholarly man. He read the Iliad and the Odyssey to Avery and me. Then when I got smarter, I read them myself. Avery, too. In fact, the two of us used to act out battle scenes. Avery always got to be Achilles because he was older and his name started with A. I had to be Hector. H for Hector, you know. Avery got to kill me every single time."

James Marshall coughed to clear his throat. "Do you recall what Achilles said before he went into battle?"

I nodded. "He knew he'd die if he fought; it was his destiny. But he decided he'd rather die a hero in battle than live out his life and die safe in his bed."

James Marshall nodded. "Heroes' names are remembered forever," he added, "but an old man's name is soon forgotten."

Mama had come upstairs while we were talking. James Marshall didn't see her, but I did. From the look on her face, I knew she hated what we were saying.

"If you aim to have a long life, you should be resting, James Marshall," Mama said sternly. "Not talking your fool head off."

"Now, now, Mrs. Magruder, I was paraphrasing Homer himself, a man we all esteem."

"Try reading your Bible instead," Mama said. "Ecclesiastes, for instance. 'For to him that is joined to all the living there is hope: for a living dog is better than a dead lion.'"

Before James Marshall could come up with a rejoinder, Mama stuck a spoonful of her medicine into his mouth. That silenced him from giving his opinion of dead lions and living dogs. But I knew he didn't agree with Ecclesiastes. Or Mama, either.

As for myself, I wasn't sure. I wanted to believe in the glory of war, but so far all I'd seen was soldiers burning farms and stealing food from folks who needed it just as badly as they did. Maybe you had to be in the actual fighting to see what Homer saw. Papa hadn't said much about his experiences, but I was certain Avery would have plenty to tell me.

"Don't just stand there dreaming, Haswell," Mama said. "Go on downstairs and do something useful. Shovel a path to the barn." She didn't sound cross. Just firm. But as I left the room, I heard her mutter, "Damn Homer and his foolishness."

I'd never heard Mama say damn anything so I figured she must be angrier than I'd realized.

***

The wind had dropped and the snow lay thick and white over the fields, carved into banks and drifts and hollows. The sun stood at the top of the blue sky, shining so bright it dazzled my eyes. Lord, it was a pretty sight. But it didn't make the shoveling any easier.

When I went into the barn to tend the cow and Warrior, I could scarcely see. Snow-blind, I guessed. The horse raised his head and whinnied, as if to say he wanted his oats and he wanted them now. I fed him and visited with him a while.

"Don't worry. Your master's on the mend already," I told him. "He'll be down to see you in no time."

Warrior seemed to understand every word I spoke. I'd never known a horse to look so intelligent. I reckoned he was the equal of Alexander the Great's noble steed Bucephalus in looks as well as brains.

By the time I

returned to the house with a bucket of milk, Mama was busy kneading bread and Rachel was drawing pictures on the steamy kitchen windows. The air smelled as sweet as a field of mown wheat on a hot summer day.

I stamped my feet to warm them and rubbed my hands together. "How's James Marshall?"

"Sleeping," Mama said. "His wound is healing nicely. Wasn't near as bad as it looked. His fever's down, too. I believe what he needed most was warmth and nourishment and sleep."

That was good news. I had half a mind to sneak up and take a peek at him. If he was awake, I planned to ask him what getting shot was like, and had he been scared, and did he ever have a chance to sit down next to Mosby and talk to him close up. But the second I put my foot on the step, Mama shook her head.

"Leave the poor boy alone, Haswell. Didn't I just say rest is what he needs?"

"Yes, ma'am." I headed for the parlor to find a book to read, but Rachel got there first.

"Read to me, Haswell." She thrust Great Expectations at me. Papa was very fond of Mr. Dickens and had acquired most of his books, including this one, the very latest. He'd managed to find a copy in Richmond and brought it home for Christmas. He'd read the entire book to us, sitting by the fire on cold winter nights.

It was simpler to read to Rachel than argue with her, so I took the book and began at the beginning, even though we both knew the story almost by heart. Pip's meeting with the convict in the foggy graveyard always gave me the shivers. Sometimes I lay awake wondering what I'd do if I ever experienced a moment like that.

"'Hold your noise!'" I read. "'Keep still, you little devil, or I'll cut your throat!'"

I did my best to speak with expression the way Papa did, but I couldn't make the convict's voice sound as gruff as he could.

"A fearful man," I read on, "all in coarse grey, with a great iron on his leg. A man with no hat, and with broken shoes, and with an old rag tied round his head. A man who had been soaked in water, and smothered in mud, and lamed by stones, and cut by flints, and stung by nettles, and torn by briars; who limped and shivered, and glared and growled; and whose teeth chattered in his head as he seized me by the chin.

Mister Death's Blue-Eyed Girls

Mister Death's Blue-Eyed Girls The Ghost of Crutchfield Hall

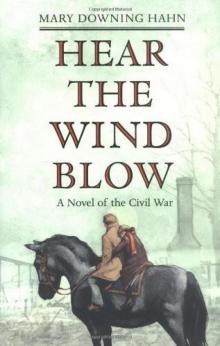

The Ghost of Crutchfield Hall Hear the Wind Blow

Hear the Wind Blow Time of the Witch

Time of the Witch The Girl in the Locked Room: A Ghost Story

The Girl in the Locked Room: A Ghost Story All the Lovely Bad Ones

All the Lovely Bad Ones One for Sorrow

One for Sorrow Deep and Dark and Dangerous

Deep and Dark and Dangerous Tallahassee Higgins

Tallahassee Higgins Promises to the Dead

Promises to the Dead Took: A Ghost Story

Took: A Ghost Story Following My Own Footsteps

Following My Own Footsteps Wait Till Helen Comes: A Ghost Story

Wait Till Helen Comes: A Ghost Story Where I Belong

Where I Belong The Spanish Kidnapping Disaster

The Spanish Kidnapping Disaster Look for Me by Moonlight

Look for Me by Moonlight The Old Willis Place

The Old Willis Place Closed for the Season

Closed for the Season As Ever, Gordy

As Ever, Gordy Anna on the Farm

Anna on the Farm The Doll in the Garden

The Doll in the Garden Daphne's Book

Daphne's Book Witch Catcher

Witch Catcher The Gentleman Outlaw and Me--Eli

The Gentleman Outlaw and Me--Eli Wait Till Helen Comes

Wait Till Helen Comes Took

Took A Haunting Collection

A Haunting Collection Anna All Year Round

Anna All Year Round The Girl in the Locked Room

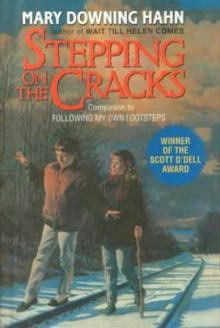

The Girl in the Locked Room Stepping on the Cracks

Stepping on the Cracks