- Home

- Mary Downing Hahn

One for Sorrow Page 18

One for Sorrow Read online

Page 18

I looked where Elsie pointed, but all I saw was the glow from the nurse’s lantern.

Elsie ducked behind me and grasped me around my waist. She held me so tightly I could scarcely breathe. I struggled to get away, sure she meant to suffocate me, but her grip was like death itself, cold and hard and merciless.

“What do you want, old lady?” Elsie shouted.

I heard no answer, but Elsie said, “I don’t need your help. I have my friend Annie and I won’t leave her!”

A breeze came up then, bringing with it the smell of lilacs. The light came closer and a hand touched my face. Slowly Mrs. Jameson began to take shape as if she’d been drawn faintly on tracing paper.

“What are you doing outside in the cold?” I cried. “I don’t understand. You should be in bed.”

“It’s all right, Annie,” she said. “I’ve come to take Elsie home.”

“Don’t believe her! She’s here to get even with me!” Elsie let me go and climbed a tree. Like a wild animal, she crouched near the top and glared down through her tangle of hair. “You hate me because I pushed you down the stairs!”

“No, Elsie, I don’t hate you. I simply want to help you.”

“Ha,” Elsie shouted. “I don’t trust you one bit. You’ll take me to the cemetery and put me in my coffin. You’ll drive a stake through my heart to make me stay there!”

“Please come down and talk to me,” Mrs. Jameson begged. “I can’t climb up there, Elsie.”

“Talk to me from where you are. I can hear you just fine, old lady.”

“Come down, Elsie.” Mrs. Jameson stretched out her hand. “Please listen to me.”

Elsie stayed where she was. “Why should I do what you say?”

“Because I can take you to your mother.”

“Liar. You don’t know my mother. You don’t know where she is.” Elsie gripped the branch she sat on and stared down at Mrs, Jameson. “If my mother loved me, she’d come for me herself.”

“She doesn’t know the way. You must go to her. And I can show you the way.”

“I don’t believe you.” Elsie yanked a pinecone from a branch and threw it at Mrs. Jameson. When it had no effect, she hurled another. Soon the air was full of pinecones. Some hit me, but none touched Mrs. Jameson.

“I don’t have much time,” Mrs. Jameson said, “and neither do you. If you don’t come down soon, I’ll be forced to leave without you. Once I’m gone, you’ll be stranded here for a long time. Believe me, you’ll be very unhappy.”

“Then go, old lady, go, and leave me be! I’m staying where I am. Even if Annie won’t help me, I’m not leaving until I get even with Rosie and the others.”

“Elsie,” I called, “please do what Mrs. Jameson says. You can trust her. She’d never lie to you.”

“Ha. As if I believe a word that comes out of your lying mouth, Annie Browne. I have a mind to stay here and torment you for the rest of your life.”

“That’s enough, Elsie.” Mrs. Jameson went to the foot of the tree. “It would break your mother’s heart to see you behaving like this.”

“She doesn’t care about me, she never did.”

“Why do you say that?”

“If she loved me, she wouldn’t have died. She would’ve stayed with me and taken care of me.”

“Nonsense.” Mrs. Jameson gazed at Elsie. “Your mother didn’t want to die.”

Elsie began to cry. “I don’t know what to do,” she wailed. “I don’t know where to go!”

I climbed up into the tree. She kicked my face with her bare feet, but I didn’t feel anything but cold.

“Go away, Annie.”

“No, not until you do what Mrs. Jameson tells you.”

She climbed higher. A branch snagged her hair, and strands of it floated away on a breeze. In the bright light, I saw she’d begun to lose her edges.

“You’re disappearing,” I whispered.

“What does that mean?” Elsie asked.

From the ground, Mrs. Jameson answered. “It means you’ll be stranded here for hundreds of years if you don’t come with me now. No one will see you, no one will you hear you. You’ll be all alone. An angry spirit doomed to harm the living but not to enjoy doing it. You’ll be miserable.”

“Maybe I won’t be miserable,” Elsie said. “Maybe I’ll like it.” Her voice shook as she spoke, and I knew she was terrified.

“Listen to what she says,” I begged. “Believe her. Go with her.”

Elsie looked at me and then down at Mrs. Jameson. Her grip on the branch loosened. “You better be telling the truth, old lady.”

Mrs. Jameson held out her arms. “I swear to you, Elsie, you’ll soon be with your mother.”

Slowly Elsie let go and floated to earth. Mrs. Jameson took her hand. “How will she know me? I was just a baby when she died.”

“Don’t worry.” Mrs. Jameson squeezed Elsie’s hand. “Mothers always know their children.”

Elsie frowned and smoothed her ragged dress. She touched her strands of tangled hair. “I look horrible.”

“You’ll look beautiful to your mother.”

While they talked, my heart swelled with grief. To lose Elsie it seemed I had to lose Mrs. Jameson, too. I hadn’t expected that.

“What about me?” I cried to Mrs. Jameson. “What will I do without you?”

“Oh, Annie, my dear, dear Annie. Soon you’ll be home with your mother and father. You won’t need me then.”

Elsie scowled at me. “She’s my friend now. Not yours.”

Mrs. Jameson sighed. “Oh, Elsie, I’m Annie’s friend, too. You must leave those feelings behind.” She gripped Elsie’s hand. “Say goodbye to Annie. We must go now.”

“Well, goodbye,” Elsie muttered.

I reached for Mrs. Jameson and tried to keep her for a moment but she and Elsie were both fading into the mist and shadows. There was nothing solid to hold.

“Farewell, my dear,” Mrs. Jameson whispered. “I’ve enjoyed the time we spent together.”

As the two of them disappeared into the night, three deer came to the edge of the pond and drank. A muskrat swam into sight, its slick head above the water. Overhead, the constellations kept their vigil.

Suddenly afraid, I ran across the grass and climbed through my window. On silent feet, I tiptoed through the corridors that led to the infirmary. I had to know. I had to see for myself.

At the infirmary door, I paused. The night nurse was asleep at her desk. In their beds the old people moaned and whimpered in their sleep. Some snored, some coughed, one whispered, “Who’s there? Is it you, Amelia? Have you come to take me home?”

Just as I’d feared, Mrs. Jameson’s bed was empty. A bare mattress stripped of sheets and blankets waited for the next occupant.

In deep sadness, I lay on her bed and looked out the window to see what Mrs. Jameson had seen. Beyond the glass was the dark sky, a sprinkle of stars, a half moon, and the constellations in their appointed places. In the distance, the lights of Mount Pleasant glowed.

“I’ll miss you so much,” I whispered to the listening dark.

I lay there, thinking about Mrs. Jameson. I smelled the smells she’d smelled. I heard the sounds she’d heard. I saw the things she’d seen. It was as if part of her had stayed in Cedar Grove to comfort me.

Just as the sky began to lighten, I tiptoed away, careful not to disturb the nurse or the old people wrapped in their dreams.

My own room was empty. And silent. I got into bed and pulled the covers up. Nobody would snatch them off while I slept. Nobody would throw my things on the floor. Nobody would hang by her knees from my curtain rod. Nobody would write on my walls.

Nobody would sing “I ain’t got no body.”

I closed my eyes and fell into the deepest sleep I’d had for a long time.

Twenty-Five

CAME HOME from Cedar Grove in April. Forsythia blazed like yellow fire. The trees were a soft golden green with the hint of new leaves, and lawns were lush with gr

ass. The sun shone, the sky glowed deep blue with a scattering of clouds, and people strolled along the streets, some walking dogs, others pushing baby carriages, boys on bikes, girls playing jump rope.

The normal world I’d missed so much had moved from winter to spring just as it always did, but I was a stranger, a convalescent, someone who had been in a rest home. Would anyone be my friend? Or would I take Elsie’s place as the outsider?

At the corner of Portman Street, Mother told me to close my eyes. “Don’t open them until I tell you to.”

Mystified, I did what she said. They must have a surprise for me—perhaps the shiny new bicycle I wanted.

The car stopped, and Mother said, “Open your eyes, Annie.”

On our front porch, my classmates let out a cheer and held up signs welcoming me home in big red letters. Miss Harrison presented me with a bouquet of roses and hugged me. “We’re so glad to see you, Annie!”

The next minute, my friends surrounded me. Everyone talked at once. They’d missed me. Had I missed them? Would I be in school on Monday? They gave me welcome-home cards they’d made in class. They hugged me. They complimented me on my dress. They admired my new patent-leather shoes. They loved the lavender ribbon in my hair.

Jane stuck by my side and clung to my hand as if I might disappear at any moment. Lucy and Eunice told me stories about school and made me laugh.

Only Rosie hung back, not quite meeting my eyes. She was thinner than I remembered. Her face was pale, and her eyes were ringed with dark circles. Her hair had lost its brightness. Worst of all, the spark that had made her our leader had disappeared.

Jane noticed me looking at Rosie. Coming closer, she whispered, “Rosie hasn’t been herself since she had the flu. She almost died, you know.”

Immediately I felt guilty about the flu mask. Why had I let Elsie make me put it in Rosie’s bookbag?

“Her mother and father are taking her to Hilltop Lodge for the whole summer. Dr. Hughes thinks the fresh mountain air will improve her health. She’ll ride ponies and swim in the lake and play tennis. Doesn’t that sound grand?”

I glanced at Rosie, still standing alone on the edge of the group. This time she looked straight at me, but she didn’t smile or wave.

Without noticing Rosie, Mother walked between us. “The cake and ice cream are ready to serve, Annie. Would you like to help me?”

I followed Mother to the table she’d set up on the porch, and the girls gathered around. While Mother cut the cake, I poured glasses of punch and Miss Harrison scooped ice cream.

Rosie was the last in line. After Miss Harrison topped her slice of cake with ice cream, Rosie lingered a moment.

“I need to talk to you, Annie,” she asked. “May I stop at your house on my way home from school?” Even her voice was different—flat and dull, barely louder than a whisper.

“If it’s about the flu mask in your bookbag—”

“No, no. Not that. I know what happened. It’s about something else altogether.”

She walked through the crowd and sat on the porch steps, where she ate her cake and ice cream alone.

When everyone had finished eating, Miss Harrison called, “It’s time to return to school, girls. Please thank Mrs. Browne for the delicious refreshments.”

The girls moaned and groaned and begged to stay longer, but she reminded them this was a special treat for me and they mustn’t tire me out. “Remember, you’ll see Annie on Monday.”

When they were gone, Mother noticed the yawns I tried to stifle. “You look like you need a nice rest, Annie. Why don’t you go to your room and lie down for a while?”

I climbed the stairs slowly and hesitated in the doorway. My bed waited, its pillows fluffed. My books stood in straight rows on shelves. Drawing supplies lay neatly on my desk. The scent of spring drifted through the open window and stirred the curtains.

A cloud moved across the sun and darkened my room. The corners filled with shadows. Frightened, I drew back. Suppose Elsie had escaped from her grave again? Suppose she waited for me in the closet or under my bed? She might appear at any moment, swinging upside down from my curtain rod or sitting in my rocking chair, gloating. She might pick up a jar of poster paint and hurl it at the wall. Mother would think I did it, and she’d send me back to Cedar Grove, and everything would start all over again.

Suddenly Mother was beside me, her arm around my shoulders. “Is everything all right, Annie?”

I turned and clung to her as if I were three years old. “Am I really home to stay?”

Her arms tightened around me. “Yes, of course you are.”

“And you’ll never send me away again, no matter how bad I am?”

“Oh, darling, we didn’t send you away to punish you. The concussion was worse than Dr. Hughes originally thought. He feared a swelling in your brain was causing your strange behavior. We sent you to Cedar Grove so you could get the rest and recuperation you needed.”

She drew back and smiled down at me. “And just look at you. Your cheeks are pink with health, and you’re yourself again. Our Annie, home to stay.”

I leaned against her, breathing in the familiar lilac scent of her face powder, and knew I was safe.

Mother smoothed my hair and kissed me. “You can’t imagine how empty this house has been without you.”

I took off my shoes and lay on my bed. Mother covered me with a light blanket and closed the curtains. Kissing me once again, she went downstairs.

Later that afternoon, Mother shook my shoulder gently. “Wake up, Annie,” she said. “Rosie is here.”

Rosie sat on the parlor sofa, waiting for me. “I’m glad to see you, Annie. I missed you.”

“I missed you, too.”

Rosie turned her head and coughed.

“Are you all right?” I asked her.

“I’m not over the flu yet,” she told me. “My mother is taking me to the mountains this summer. Dr. Hughes believes fresh air is what I need to get my strength back.”

“Jane told me. She says there’ll be ponies and tennis and swimming. It sounds wonderful.”

Mother appeared with a tray and two glasses of lemonade. “Would you like to sit on the porch? It’s a lovely day.”

We followed her outside and sat side by side on the swing. I knew Mother was worried about Rosie, and I was glad she’d thought to bring us something to drink.

After Mother went back inside, Rosie said, “I didn’t come here to talk about Hilltop Lodge.”

Something about her voice and the look in her eyes made me nervous. “What do you want to talk about, then?”

I waited for her to go on, but she gazed silently across the lawn, beyond the tallest trees to the sky darkening now and then with passing clouds. She sat with her arms folded tightly across her chest, as if she were holding herself together. Tiny threads of blue veins were visible under the skin of her temples.

Although I’d never known Rosie O’Malley to be afraid of anything, she was definitely scared. “Tell me, Rosie,” I begged. “What’s frightening you?”

Without looking at me, Rosie told me. “While I was sick I had terrible dreams—not nightmares, much worse than nightmares. Dr. Hughes said they were hallucinations brought on by my fever. But I think they were real. She really was in my room, Annie. Every night, every single night, she sat on my bed and watched me. She was waiting for me to die. She knew I would. I was too sick to live much longer.”

“Who?” I asked. “Who was sitting on your bed?” I waited for her to tell me, but I knew the answer already.

“You know,” Rosie said. “You saw her, too.”

Before I could say Elsie, Rosie pressed a thin, cold finger against my mouth. “Don’t say her name. Don’t ever say her name!”

“Why not?”

Rosie stared past me as if she saw something stir in the shadows under the fir tree. “She might think you’re calling her.”

I peered into the shadows too. I saw nothing but a slight movement in

the branches. The wind, I told myself, just the wind passing through. Not her, not her. But how many times had I said her name after she’d gone away? If Rosie was right . . . No, don’t think about it, I told myself. She’s gone, gone, gone. Forever gone.

Rosie spoke so softly I had to lean close to hear her. “She told me she made you put the flu mask in my bookbag. She said she gave me the flu because I stole her mask and she caught the flu and died. I had to pay for her life with mine unless I became her friend. I told her I’d rather die. She said it made no difference. Alive or dead, I’d never get away from her.”

I stared at Rosie in amazement. “She told me the same thing. We’d be friends forever, just her and me, nobody else. She wanted me to help her pay back her enemies, starting with you.”

Rosie seized my hands. “Oh, Annie, what will she do to us?”

I squeezed Rosie’s cold hands. “She can’t do anything to you or me or anyone else. She’s gone forever.”

“How do you know that?”

“I saw her go.” While Rosie huddled beside me in the swing, I told her about my last night with Elsie. “She left peacefully. She won’t come back.”

Rosie sighed deeply. We sat side by side, gently rocking the swing back and forth, back and forth. The only sound was the creak of the ropes. The sun was low now, and the shadows on the lawn were darker and longer.

On the other side of town, evening shadows crept across Forest Heights Cemetery. A solitary crow perched on the outstretched hand of a stone angel. The wind blew, and the shadows shifted. Slowly the crow lifted its wings and flew away into the dark sky.

Counting Crows

One Crow for sorrow,

Two Crows for mirth;

Three Crows for a wedding,

Four Crows for a birth;

Five Crows for silver,

Six Crows for gold;

Seven Crows for a secret, not to be told;

Eight Crows for heaven,

Nine Crows for hell;

And ten Crows for the devil’s own self.

—Counting Rhyme (from The Folklore of Birds, by Laura C. Martin, 1993)

Mister Death's Blue-Eyed Girls

Mister Death's Blue-Eyed Girls The Ghost of Crutchfield Hall

The Ghost of Crutchfield Hall Hear the Wind Blow

Hear the Wind Blow Time of the Witch

Time of the Witch The Girl in the Locked Room: A Ghost Story

The Girl in the Locked Room: A Ghost Story All the Lovely Bad Ones

All the Lovely Bad Ones One for Sorrow

One for Sorrow Deep and Dark and Dangerous

Deep and Dark and Dangerous Tallahassee Higgins

Tallahassee Higgins Promises to the Dead

Promises to the Dead Took: A Ghost Story

Took: A Ghost Story Following My Own Footsteps

Following My Own Footsteps Wait Till Helen Comes: A Ghost Story

Wait Till Helen Comes: A Ghost Story Where I Belong

Where I Belong The Spanish Kidnapping Disaster

The Spanish Kidnapping Disaster Look for Me by Moonlight

Look for Me by Moonlight The Old Willis Place

The Old Willis Place Closed for the Season

Closed for the Season As Ever, Gordy

As Ever, Gordy Anna on the Farm

Anna on the Farm The Doll in the Garden

The Doll in the Garden Daphne's Book

Daphne's Book Witch Catcher

Witch Catcher The Gentleman Outlaw and Me--Eli

The Gentleman Outlaw and Me--Eli Wait Till Helen Comes

Wait Till Helen Comes Took

Took A Haunting Collection

A Haunting Collection Anna All Year Round

Anna All Year Round The Girl in the Locked Room

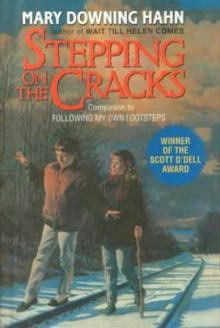

The Girl in the Locked Room Stepping on the Cracks

Stepping on the Cracks