Mister Death's Blue-Eyed Girls

Mister Death's Blue-Eyed Girls The Ghost of Crutchfield Hall

The Ghost of Crutchfield Hall Hear the Wind Blow

Hear the Wind Blow Time of the Witch

Time of the Witch The Girl in the Locked Room: A Ghost Story

The Girl in the Locked Room: A Ghost Story All the Lovely Bad Ones

All the Lovely Bad Ones One for Sorrow

One for Sorrow Deep and Dark and Dangerous

Deep and Dark and Dangerous Tallahassee Higgins

Tallahassee Higgins Promises to the Dead

Promises to the Dead Took: A Ghost Story

Took: A Ghost Story Following My Own Footsteps

Following My Own Footsteps Wait Till Helen Comes: A Ghost Story

Wait Till Helen Comes: A Ghost Story Where I Belong

Where I Belong The Spanish Kidnapping Disaster

The Spanish Kidnapping Disaster Look for Me by Moonlight

Look for Me by Moonlight The Old Willis Place

The Old Willis Place Closed for the Season

Closed for the Season As Ever, Gordy

As Ever, Gordy Anna on the Farm

Anna on the Farm The Doll in the Garden

The Doll in the Garden Daphne's Book

Daphne's Book Witch Catcher

Witch Catcher The Gentleman Outlaw and Me--Eli

The Gentleman Outlaw and Me--Eli Wait Till Helen Comes

Wait Till Helen Comes Took

Took A Haunting Collection

A Haunting Collection Anna All Year Round

Anna All Year Round The Girl in the Locked Room

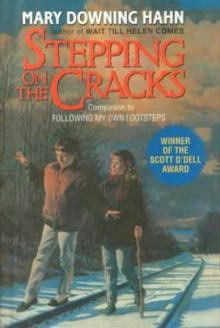

The Girl in the Locked Room Stepping on the Cracks

Stepping on the Cracks